David Thompson gives motivational speeches, tends to his wife, Cathy, and eagerly awaits his first grandchild, due in June. Tom Burleson oversees building inspections for the rural North Carolina county that he grew up in, raises funds for the medical mission that his ministry supports and helps his son with their Christmas tree farm.

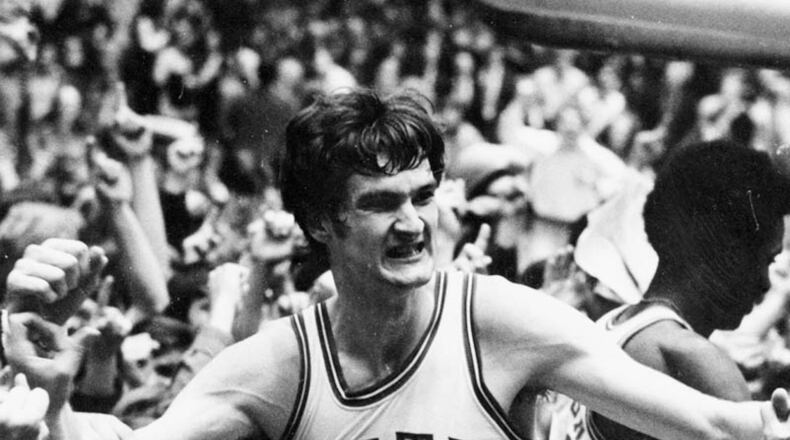

The two central forces on one of the more memorable NCAA championship teams — the 1974 N.C. State Wolfpack — speak with gratitude for their station in life 39 years after they rose to the top of college basketball.

“There’s been a lot of ups and downs, but everything’s going really well,” Thompson said. “God’s been good.”

Said Burleson, “I’ve just been very blessed.”

The two fondly remember the season — the early-season loss to UCLA, the epic overtime win over Maryland in the ACC tournament final, the double-overtime win against the Bruins in the national semifinals — as do the millions of fans, some of whom can recall it even more clearly.

Thompson is now 58, living in Charlotte, N.C. Burleson is 61, in Newland, N.C. They remain friends. Thompson calls Burleson a “good Christian brother.” Time moves on.

Said Burleson, “There is life after basketball.”

In 1974, life was basketball. Thompson was brilliant, playing in the second of a three-season college career (freshmen were still ineligible to play at that point) in which he averaged 26.8 points per game, was a three-time All-American and was a two-time player of the year.

For the generations that never saw his acrobatics, perhaps the most apt honorific is that he was Michael Jordan’s favorite player, so much so that Jordan requested Thompson to present him for induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

When he sees video clips of his playing days, even Thompson himself is a bit dazzled.

“You look at yourself, and you’re amazed at some of the stuff you did when you were 19, 20, 21 years old,” he said.

Burleson was a 7-foot-4 force, a three-time All-ACC selection who also was named to the 1972 U.S. Olympic team and was the third overall pick of the 1974 NBA draft. He averaged a double-double in each of his three seasons at N.C. State.

In 1973-74, N.C. State compiled a 30-1 record, losing only to UCLA in the third game of the season. Burleson can recall even the date of the game (Dec. 15), an 84-66 loss in which Burleson broke his nose on an elbow to the face.

Despite the lopsided score, “David and I watched the tape, and we knew that we could play with them after that,” Burleson said. “We knew that they were a great team, but they weren’t really better than us.”

Three months later, they got their vindication by beating UCLA and Bill Walton 80-77 in double overtime in the national semifinals, ending the Bruins’ run of seven consecutive national titles. The win over Marquette in the final was practically perfunctory.

After Thompson turned professional, substance abuse led to the ruin of his career, personal life and finances. His life turned around, he said, when he made a commitment of Christian faith in 1988. He said he has been clean and sober ever since.

Married to his wife, Cathy, he has two daughters, Brooke, a professor at Gardner-Webb, and Erika, who works with Thompson’s agent and who received her N.C. State degree on the same December 2003 day that her father finally received his.

Thompson’s days are spent caring for Cathy, who suffers from diabetes, and with speaking engagements, often sharing the story of his recovery at schools and camps.

Of his playing days, Thompson said, “It seems like a different life. It really was.”

Burleson could say likewise. After his NBA career ended in 1981, Burleson returned home to North Carolina, where he raised three sons with his wife, Denise, and became an electrical contractor before he dove into local politics, serving two terms as a county commissioner from 1992-98.

Retirement looms in a few years. Besides limited involvement with the family Christmas tree farm, he intends to stay occupied with his Christian ministry, which supports a medical mission in Malawi that includes a hospital, clinics and an orphanage. He’s taking a team to Malawi in May that will take supplies and provide support. To Burleson, the connection between a country boy from North Carolina and a hospital in an underdeveloped southeastern African nation is miraculous.

“It’s got to be God’s work because I couldn’t have put it together,” he said. “There’s no way.”

Thompson and Burleson still follow college basketball and support the Wolfpack. But, once defined by a game and a moment in time, they have found greater meaning far from the court.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured