Morehouse School of Medicine building awareness, availability, trust

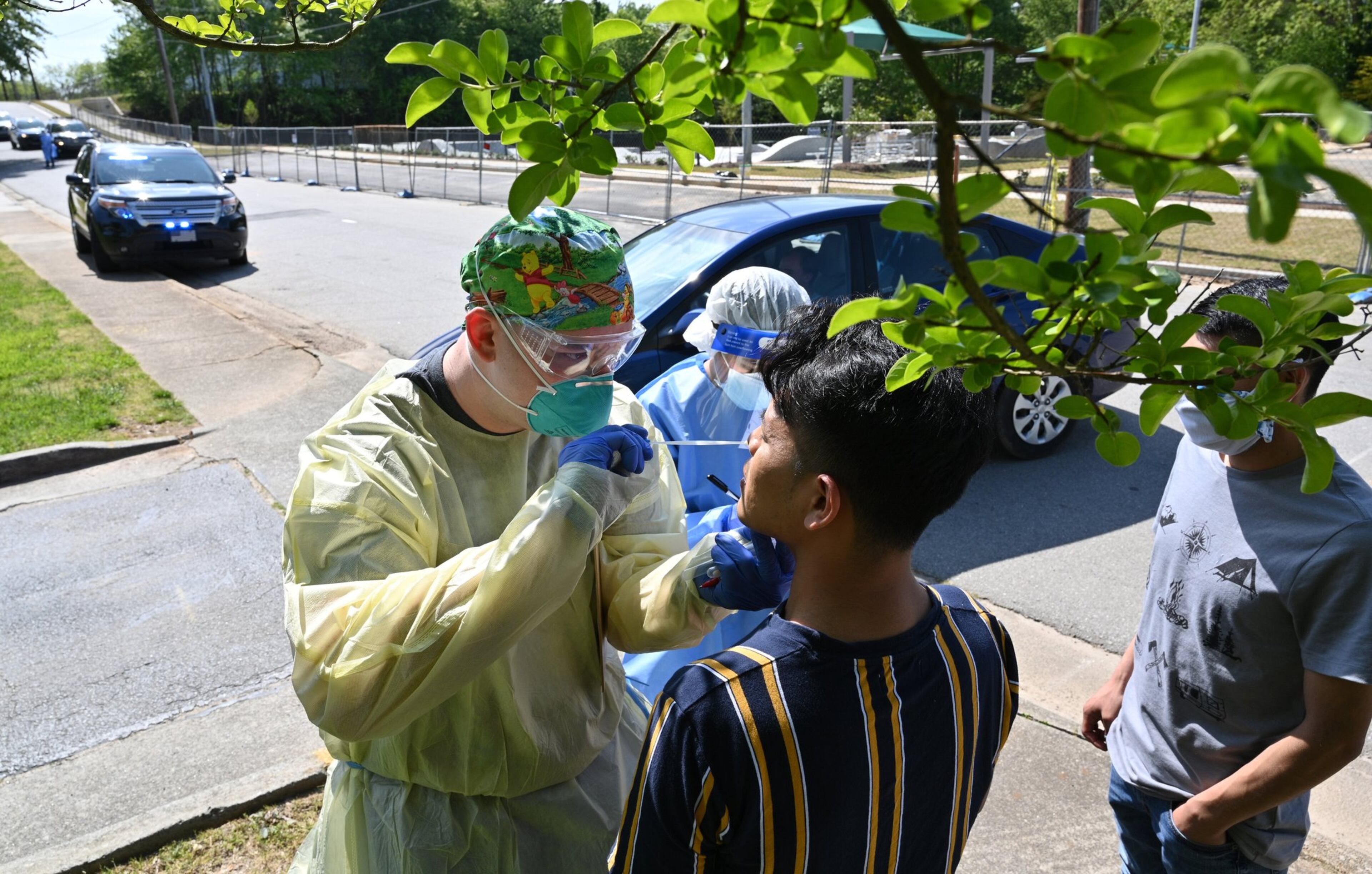

The Morehouse School of Medicine HEAL Clinic (Health Equity for All Lives) is bringing health care to those who need it through volunteering and grass roots community outreach. It’s a local effort for a national issue.

“There’s really not a single city in this country that really is spared by health disparities,” Dr. Harris Hooker, vice president and executive vice dean of research and academic administration, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “And what we know, and the country knows, is that there are social determinates of health that really directly impact those health disparities and what we are trying to get to in terms of health equity. But we also know now... (there are) not just social determinates of health... but also political determinates of health that really have a big impact on health. So it’s both the social and political determinates of health that we at Morehouse School of Medicine look to address that across the board.”

When it comes to the Peach State, nearly every county is considered medically underserved.

“We know that, unfortunately, that of 159 counties in Georgia, there are 148 that are designated as medically underserved,” she said. “Isn’t that tragic? What’s meant by that is there are not enough providers. There are not enough physicians in those counties to provide health services to those populations.”

While the pandemic has exasperated the health care industry, health inequity has plagued the country for decades.

“This has been the case for many years,” she said. “What it is, is the result of not having enough trained physicians to service our populations — which is one of the reasons why Morehouse School of Medicine came into existence. Generally, in those many small counties, you have to be focused on training those young folks in primary care, which is our key focus. I want to emphasize that we have many students that go into all kinds of specialties, but we were developed and came about to address the shortage of health care professionals within the state of Georgia.”

Across the state, community members are driving significant distances just to see a health care professional. Morehouse School of Medicine is training primary care health professionals to go to those counties — bringing the health care straight to the where it is needed.

“When we start talking about underserved populations, we need to talk about things like poverty…access to healthy food, lack of quality educational systems and then access to health care,” Hooker said. “All of those are factors that really make up health disparity. As I said, we came into existence to address the shortage in health professionals. That’s not just medical doctors. Many don’t know that in addition to the M.D. degree, we have programs with physician assistant programs. We have programs that train and develop our public health folks. We have robust programs in developing researchers. We have designed our research programs to address those disparities in health. We’re talking about blood pressure. We’re talking about hypertension. We’re talking about heart disease. We’re talking about stroke. We’re talking about the prevention of HIV and AIDS. And we are recently talking about COVID-19.”

While Hooker handles the research that pushes the school of medicine’s missions forward, Dr. Christopher Ervin, program manager for community engagement at MSM, is helming the school’s HEAL unit.

“I’m itching to get our mobile health services even more mobile,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “More mobile and more visible within the community.

“When an organization, community or institution says ‘We would like a health fair and would like Morehouse School of Medicine to be present,’ that usually falls under my purview with the clinic and with the mobile health team.”

Once they are on site, the HEAL Clinic has one mission in mind — free health care.

“There’s been many occasions where we’re checking someone’s blood pressure,” he said. “They turn out to have high blood pressure, or we’re checking someone’s blood sugar and it turns out they have high blood sugar. First they call me over... and invariably it ends up being, ‘I don’t have health insurance,’ or ‘I ran out of my medications,’ or ‘I don’t have access to a doctor,’ and we can immediately say you can be seen in our clinic.”

Operated by students and volunteers, it’s a clinic that’s making a difference.

“The students you see around you, they’ll be taking care of you in the clinic,” he said. “That is rewarding for us because this is the purpose of doing the screenings, to identify people that need care. I think it is rewarding for the students because they can now see the benefit of the activities, because sometimes it’s difficult for students to say, ‘Why am I giving up my Saturday to be out here to do a health fair?’

“And then they realize that I can now see this patient in the clinic. And for the community members, they feel hopeful that now they can get the health care that they’ve been lacking for weeks or months.”

Mobile Healthcare Association executive director Elizabeth Wallace said mobile health clinics like Morehouse’s are an important tool in the fight against health inequity throughout the country.

“That’s what makes mobile health care interesting and exciting,” Ervin said. “Prior to joining Morehouse School of Medicine, I did a lot of community-based working activities. And in one of my discussions, we were talking about health inequities and health access. I think I’m the one who coined it first, so I’m going to claim it — what I call health actuality, that access means nothing without actuality.raditional health care delivery models.”

It all comes down to three important values: access, awareness and trust.

“That’s what makes mobile healthcare interesting and exciting,” Ervin said. “Prior to joining Morehouse School of Medicine, I did a lot of community-based working activities. And in one of my discussions, we were talking about health inequities and health access. I think I’m the one who coined it first, so I’m going to claim it — what I call health actuality, that access means nothing without actuality.

“It does not matter if someone has insurance. I live on the Southside, so I live in South Fulton. So it means if I have health insurance in South Fulton, but I have to go downtown or to Gwinnett for health care … because I don’t have a car … . If I don’t have reliable transportation, if my job requires me to be on site from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. ... what does access mean? Because I still don’t have actual health care.”

Donations are ultimately what get the HEAL Clinic to where it is needed.

“This is why we need donations,” he said. “So we’ve always had the large 39 foot unit. So that’s the one that is the size of a MARTA bus, but we are also waiting on the receipt of two sprinters. Basically the Amazon delivery vans are like the iconic sprinters. Those are great, particularly for urban-based mobile health care.

“I’m about to pack up a Chevy suburban, seriously,” Ervin added. “So the sprinter vans will allow us to do screening activities and some point of care services, vaccination services. And so definitely looking forward to having those sprinter vans, because we had to cut back on our rural presence.”

While the HEAL Clinic is looking forward to those sprinter vans, Hooker said the school is reaching toward other milestones as well.

“We started Morehouse School of Medicine with approximately a class of 24,” she said. “We moved, about three years ago now, to a class of about 56. We are proud to say three weeks ago now we brought on a class of 125 students.”

The school is also making strides in its research.

“We want to continue to build our clinical research enterprise,” she said. “What that means, in terms of a goal to impact these health disparities, is that the more trials we bring on, the more folks of color that we can reach out and enroll in trials, and the more we will be able to educate those that are reluctant to participate in clinical trials. That has to do primarily with the trust factor. We are talking about years and years ago, but folks have basically not forgotten Tuskegee. So we have built a level of trust with these communities that took time over the years. As we move forward, we want to continue to build on that trust to educate them in terms of what it means for them to participate in a trial that is looking at a certain drug or what have you. If it’s not even about them being impacted by it — it’s their children and their grandchildren ... their families. It’s generational.”

Partnering with CommonSpirit Health, which has more than 1,000 care sites and 140 hospitals across 21 states, Morehouse is now also bringing its services across state lines.

“What they bring to the table is the array of health systems across the country,” she said. “So Morehouse will have regional campuses in several of the cities where CommonSpirit Health already has a health system.”

For more content like this, sign up for the Pulse newsletter here.