How changes in Henry, Rockdale helped Biden capture Georgia

Twelve years ago, Henry County Democrats couldn’t find anyone willing to lease them office space.

Members organized for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign and down-ballot candidates from volunteers’ homes, in neighboring Clayton County and even at a local Caribbean restaurant. When a local business owner agreed to let the party use his office after hours, his landlord gave him an ultimatum: boot the volunteers or lose his lease, according to Mike Burns, chairman of the Henry County Democrats.

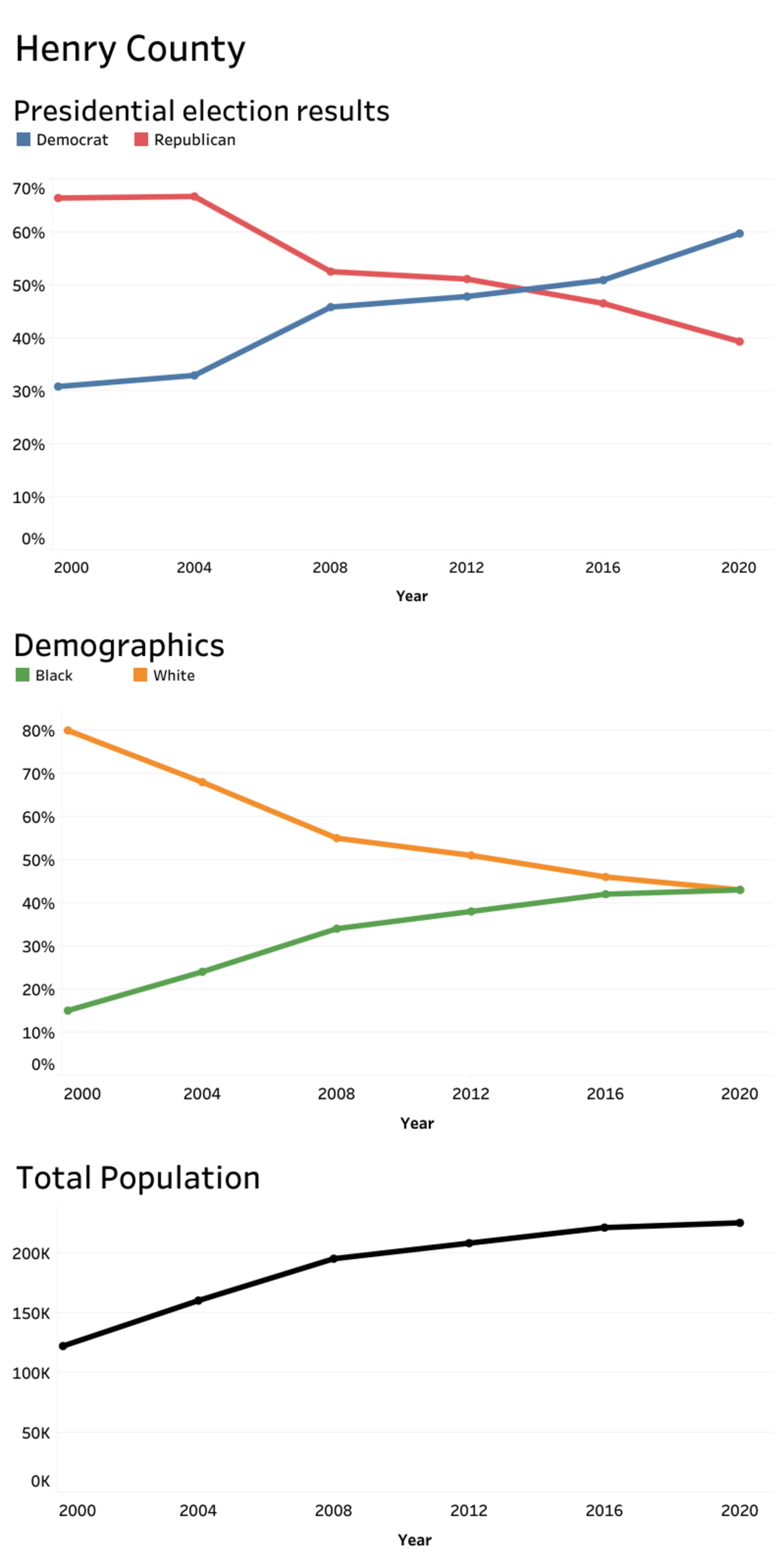

Neither clout nor office space was an issue in 2020. Democrats flipped the county chairmanship, the sheriff’s office and a fourth seat on the county commission, giving them a majority on the six-member panel. And where Obama lost Henry by nearly 8 percentage points in 2008, Joe Biden carried it by more than 20.

The political transformation of Henry County — a once rural, majority white, Republican enclave made famous by the late Herman Cain — is emblematic of the suburban population increases, demographic changes and broader cultural shifts that helped fuel Biden’s victory in Georgia last month.

An analysis by Democratic data firm TargetSmart found that of all the counties in the country, Henry had the single largest swing towards Democrats when compared to 2016. (Biden’s win over President Donald Trump in Henry was 16 percentage-points higher than Hillary Clinton’s.) Neighboring Rockdale County had the nation’s second largest, with a 14 percentage-point shift towards the Democrats.

Activists, longtime residents and observers say many factors contributed to the political metamorphosis.

Both Henry and Rockdale experienced seismic population growth over the last several decades, driven by an influx of new Black residents and exodus of some white ones. That enabled local Democrats to begin organizing in a way they hadn’t since Georgia’s political realignment in the 1990s.

Driving up vote totals in the majority-minority suburbs south and east of Atlanta will be essential for Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff on Tuesday, as they aim to unseat Georgia’s Republican U.S. senators, said Andra Gillespie, a political science professor at Emory University.

“This is going to be a close election, so Democrats and Republicans need to find every vote everywhere they can find it,” she said.

Early voting numbers in both counties show voter enthusiasm for Tuesday’s runoffs is high, especially in Rockdale.

Newcomers arrive

As he analyzed who voted in Georgia last month, Tom Bonier, CEO of the Washington-based TargetSmart, came across something different in Rockdale and Henry counties.

Statewide, turnout surged across every major demographic group. But that wasn’t the case southeast of Atlanta.

White non-college voters’ share of the electorate plunged a respective 8 and 9 percentage points in Rockdale and Henry when compared to their 2016 turnout. Black voters, meanwhile, grew to represent a plurality of the votes cast in Henry (48%) and the majority (60%) in Rockdale.

Those shifts correspond with the major demographic changes those counties have experienced over the last several decades.

Rockdale saw the largest percentage-point shrinkage in its white population of any Georgia county between 2010 and 2019, decreasing from 45% of the population to 32%, according to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution analysis of estimates from the Census’ American Community Survey.

Henry, meanwhile, had the state’s third-largest contraction of white residents, from 56% to 43% in 2019, even as the overall population exploded. As recently as 1980, Henry was 81% white.

When Democratic state Sen. Emanuel Jones first moved to Henry three decades ago, just about every elected position in the county was held by white Republicans. As a leader in the local Democratic Party in the mid-1990s, he struggled to recruit political challengers.

“We were kind of a party in name only,” said Jones, who was elected to the Georgia Senate in 2005.

But things began to shift about two decades ago. People of color began to move in, seeking larger homes, good schools and an easy commute to downtown Atlanta. Black celebrities flocked to the upscale communities in the northern part of the county, including basketball legend Shaquille O’Neal and comedian Chris Tucker.

Between 2000 and 2018, Henry’s Black population skyrocketed, from less than 18,000 to 104,000, according to data from the Atlanta Regional Commission.

A similar transformation was occurring next door in Rockdale, which attracted more middle-class residents due to its lower median home prices. Some were families seeking better educational opportunities for their children after Clayton County Schools lost its accreditation in 2008. A notable number of new Black residents were northerners who had family roots in the area, reversing the Great Migration of the early 20th Century.

At roughly the same time, some of the counties’ longtime white residents began to depart, a dealing a blow to the ruling Republican Party. Some died out. Others were turned off by the new traffic and rising property taxes. And some left for a different reason.

“Initially when the (demographic) changes happened, a few people just up and left,” said Jay Jones, a former reporter and editor for The Rockdale Citizen. “To me it was a (mark) of simply being racist — they don’t like living with Black people so they moved out.”

‘A new energy’

Local Democratic Party officials watched election results tighten year after year and jumped to take advantage.

“All the newcomers wanted to see people who looked like them (in elected politics) and who they could have a conversation with,” said Cheryl Board, the chairwoman of Rockdale Democrats.

The party amped up its efforts to recruit more Black candidates in 2006, but the “watershed year,” in Board’s eyes, came in 2008. Obama’s candidacy stirred up excitement in a way Democrats hadn’t been able to generate in decades.

“It was like a new energy,” said Jones.

Obama became the first Democrat to carry Rockdale in more than a generation. His win was coupled with one by Democrat Richard Oden, an Ohio transplant who became the first Black man elected chairman and CEO of the county.

Momentum was starting to build. In 2012, Oden and the party assembled what became known as the “slate of eight,” a group of Black Democrats that ran for every countywide office and often made joint appearances on the campaign trail.

That year, a white Republican member of Rockdale’s Board of Elections penned an editorial on a conservative website that described the county as a “little white plane” that became blacker over time and was eventually hijacked by liberals he predicted would bring “crime, incompetence, cronyism and corruption.”

The author insisted the piece was misunderstood and that it was not racist. Even so, the slate of eight swept all county offices, from sheriff and coroner to tax commissioner and magistrate judge.

JaNice Van Ness, a former Republican county commissioner in Rockdale who was unseated in 2014, said her party did not do enough at the time to reach out to newcomers.

“It was almost like if you want to join our party, come on, but you have to do the work on your end,” said Van Ness, who went on to serve in the state Senate and now works as an education administrator.

Henry’s political transformation took longer but also wasn’t without its flashpoints.

Stockbridge became host to a tense racial standoff in 2017 when residents of the affluent, majority-white Eagles Landing sought to peel off and form a new, more affluent municipality.

Clinton managed to narrowly carry Henry County in 2016, but that win didn’t transfer down-ballot. Still, it helped energize Democratic-allied groups on the ground to register and rally voters behind Stacey Abrams’ 2018 gubernatorial bid and this fall’s presidential contest.

“Now you’ve got people from all over the country sending direct mailers, making phone calls, sending text messages” for the runoff, said Burns, the Henry Democratic chairman.

“The turnout,” Burns predicted, “is going to be huge.”

Newsroom data specialist Jennifer Peebles and reporter Leon Stafford contributed to this article.

Changing demographics

This story on the gains Democrats have made in Henry and Rockdale counties is part of a series examining demographic changes that played a part in the November election and could affect the outcome of the Jan. 5 Senate runoffs.

Coming Thursday, a look at the conservative counties beyond metro Atlanta that Republicans see as their best chance of countering Democratic growth in the suburbs.