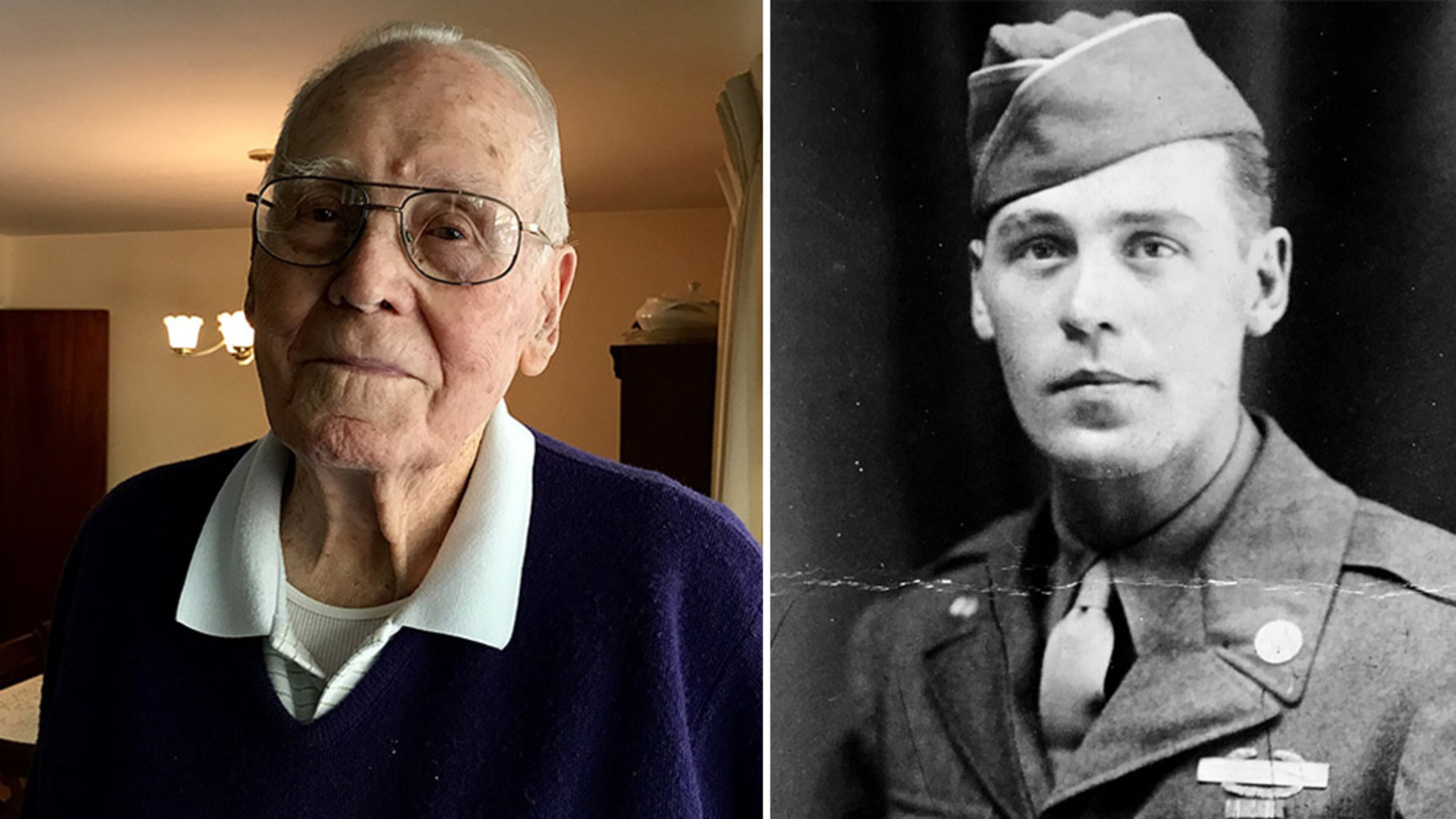

On Veterans Day, foot soldier’s memory marches on

Things were fine. Elbert Dobbs had a job that was important to the war effort, if perhaps repetitive. Folding parachutes for the guys who were dropping into battle zones? Things could be worse: He could be one of those guys.

Then he got the notice. Dobbs came home and told his wife, Daisy: The Army needed him.

“I had a wife and two little children,” said Dobbs, now 96. “You can imagine how I felt about that.”

You also can imagine that the Army said, too bad, soldier. A war needed winning, and that called for soldiers to replace those who weren’t coming home.

Dobbs, 24 at the time, kissed Daisy goodbye. He became one of millions — those who have served our nation in good times and bad.

Friday is Veteran’s Day, a holiday set aside to honor those men and women. This is no small thing: America is home to more than 20 million veterans — an estimated 750,000 in Georgia. Of that total, a rapidly dwindling number served in World War II. A count last year estimated that fewer than 700,000 survive out of the 16 million who served in that 1941-45 conflict. About 20,000 call Georgia home.

Some, like Dobbs, were reluctant soldiers. In late 1944, he reported to Camp Blanding, a training facility in central Florida. There, the Army taught him how to use the M-1, a weapon found in every battle theater on the globe. He’d become intimately familiar with it.

“It was a good rifle,” said Dobbs, who’d learned to hunt while rambling the woods of Walton County as a teen.

The year passed, and 1945 bloomed with the hint of an Allied victory. Dobbs and other troops boarded the troop ship S.S. Brazil in New York for a restless passage to the coast of France, taken in D-Day months earlier.

“I was scared from the moment I got on the boat to the moment I got home.”

They landed near a coastal village whose name he cannot recall. There, he joined other soldiers in “cigarette camps,” temporary camps named after cigarette brands in an attempt to confuse any enemy ears eavesdropping on Allied radio chatter. An officer assigned him to a tank battalion, where others discovered the error. He was trained to fire a rifle, not drive a tank.

A day later, he was sent to the 42nd Infantry Division, the “rainbow brigade.” Its insignia then, as now, is a quarter rainbow, a cascade of color.

The 42nd was far to the west, near Wurzburg, Germany. To get there, “I walked, rode on trucks, rode on tanks.” He smiled. “I’d do anything to keep from walking.”

With him was a North Carolina boy named Kenneth Blanton. He was 18, and they’d been pals since meeting in Florida.

They were buddies for the rest of Blanton’s life, which ended on the road from Wurzburg to Munich.

“I was on a truck when some Germans started shooting,” he recalled. “I jumped off and rolled down a hill.”

Blanton, just behind him, also jumped. Three bullets found the boy from North Carolina. The teen rolled down the hill to where his friend lay. “He was dead when he got to the bottom of the hill.”

Arriving in Munich, the soldiers of the 42nd readied to take another target — Dachau, the Nazi death camp. The camp housed Jewish prisoners, political dissidents and others deemed enemies of Hitler’s Third Reich. The camp operated from 1933 to its liberation in spring 1945. Anywhere from 32,000 to nearly a quarter-million people died there; the estimates vary that much.

Dobbs remembers standing outside its walls. “You could see bodies,” he said. “Dead bodies. Everywhere.”

The living hardly looked better. “They were just skin and bones.”

An officer told him and a handful of other soldiers to patrol the road from the camp to Munich. To his relief, Dobbs never passed through the gate that, for so many, had opened only one way.

The war, and the 42nd, moved on. Dobbs eventually found himself in the Bavarian Alps, staying in an old apartment building. In the distance, atop a mountain, was Berghof. It was Hitler’s vacation hideaway, a place where evil surely flourished.

“Some soldiers went up there and visited it,” said Dobbs. “But I never did.”

Instead, he stayed busy helping process German prisoners of war. He escorted one, an SS officer, to another town. There, officials released the POW. Dobbs thought he’d never see the man again. He was wrong.

“Two days later he came to see me,” said Dobbs. “He gave me a bottle of schnapps.” A gift, presumably, for humane treatment.

The war didn’t last much longer for Dobbs. He got an early discharge to return home to a wife and two little girls. In November 1945 he was back where he began at his home in Atlanta.

He resumed a civilian’s life. Dobbs got a job driving trucks, logging 3.5 million miles delivering refrigerated food across the Midwestern United States. Retiring as a driver, he then trained other truckers for the company that hired him when he was not long out of the Army.

He and Daisy added three more girls to the two they already had. They were married 58 years, until her death in 1998. “I don’t think you would find a more perfect person than her,” he said.

These days, Dobbs lives in a ranch house on a shady street in Peachtree City. It’s a quiet place whose rooms are filled with photos of family. One wall in the dining room features a framed map detailing the rainbow division’s push into the heart of World War II Germany.

Out back, he keeps a bowl of food for a feral cat he’s been trying to tame for three years. They’ve reached an agreement: Dobbs can feed the cat; the cat will let him watch.

Every week, one of his daughters visits to take Dobbs shopping and to eat lunch. Just as regularly, a granddaughter stops by with the old man’s great-great-granddaughter. Come December, that child will be 4. He cannot talk about her without smiling.

Nor can he recall that long-ago war without a sober pause, a moment’s reflection. He recently attended a reunion of World War II veterans at First Baptist Church in Peachtree City. Eleven came. Another reunion, he knows, may not attract as many. Mortality is always on the march.

But that’s a worry for another time. This old foot soldier is happy for this life, this now, this Veteran’s Day.