The five-column headline that greeted readers of The Atlanta Constitution roughly a century ago is an eerie reminder of the parallels between the coronavirus and another debilitating pandemic that swept across the state.

“Public gathering places closed by city council for two months,” announced the front page of the Oct. 8, 1918 edition. “Unless otherwise changed, instructions will shut the doors of movies, theaters, schools, churches and pool and billiard parlors.”

The Spanish flu introduced Georgians to many of the scenarios that have come to define the state’s coronavirus response over the last month: a medical system stretched dangerously thin, pleas for social distancing and mask-making campaigns.

The stories that plastered the pages of the Constitution and its rival The Atlanta Journal show public officials were grappling with many of the same problems that have weighed down Gov. Brian Kemp, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and other local leaders in recent weeks, including limited directives from Washington and sometimes diverging business and public health concerns.

“Even with all of our technology and smarts we have going for us today, I’m not sure we’re reacting much differently than they did in 1918,” said Stan Deaton, senior historian at the Georgia Historical Society. “It’s difficult to get people to give up freedom and community.”

» COMPLETE COVERAGE: Coronavirus in Georgia

There are, of course, many differences between now and then. A world war was still being waged when the Spanish flu was recorded on U.S. shores in spring 1918, which siphoned resources from public health efforts.

Medical understanding of infectious diseases was still in its infancy. Scientists didn’t prove influenza was caused by a virus until the 1930s, and the first flu vaccine and mechanical ventilators weren’t developed until a decade later. That left many suffering Georgians to resort to alternatives with questionable benefits, including laxatives, bloodletting and even whiskey.

Georgia arrival

NOW: The first coronavirus cases in Georgia were announced by the Department of Public Health on March 2. They were attributed to a Fulton County father who had recently returned from a trip to Milan, Italy and his 15-year-old son.

THEN: Soldiers returning home from the trenches of World War I are believed to have caught the Spanish flu first. Military camps proved particularly fertile ground for the highly contagious virus.

Influenza was first reported in Georgia near Augusta’s Camp Hancock. In metro Atlanta, cases soon emerged at Camp Gordon, on the site of what is now the DeKalb-Peachtree Airport.

The Sept. 18, 1918 edition of The Atlanta Constitution reported that the entire Second Infantry Replacement Regiment was placed under quarantine within days of returning to Gordon from the rifle range at Norcross.

“No cause has been announced as to the possible source of the disease, and none of the cases have assumed a dangerous nature, it is understood,” the article stated.

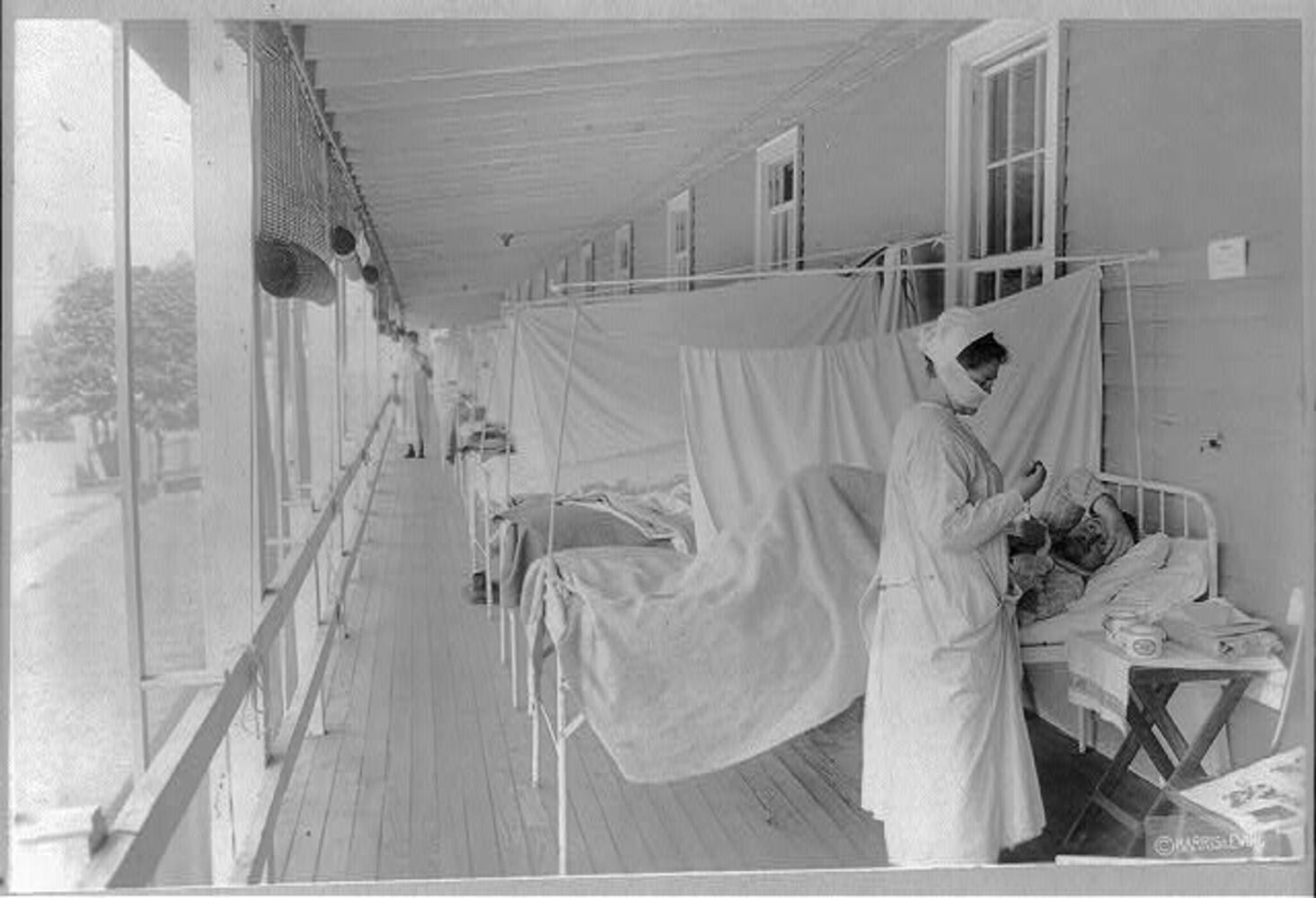

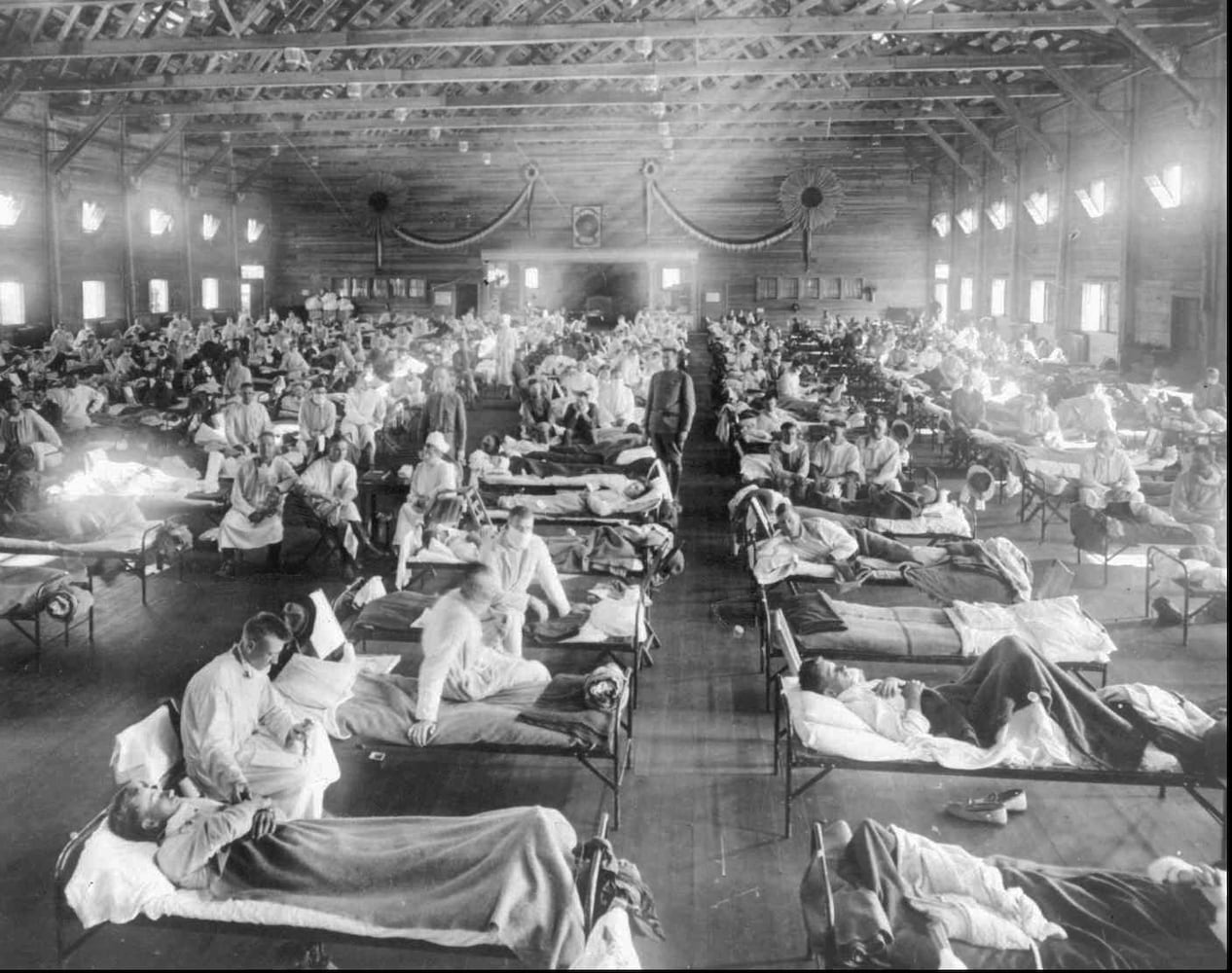

The illness, however, quickly spread. By early October, there were more than 1,900 cases reported at the camp, according to the University of Michigan’s Center for the History of Medicine, and overwhelmed medical officers issued a call for 75 trained nurses from Atlanta to volunteer.

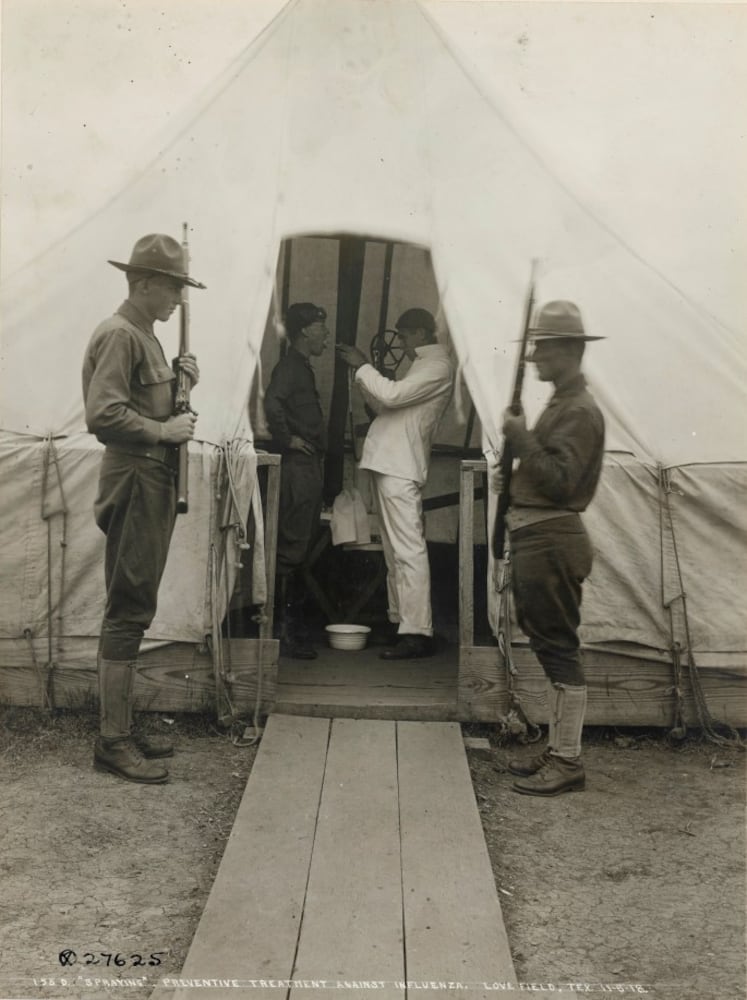

The camp’s leadership eventually bolstered sanitary measures in the barracks. Soldiers and officers were ordered to wear masks and sleep outdoors, since fresh air was believed to help avoid transmission.

Among the nearly 2,000 men admitted to Gordon’s infirmary for influenza or pneumonia during the pandemic, 94 died, according to the University of Michigan.

Elected officials respond

NOW: State leaders were initially hesitant to impose large-scale restrictions on movement and business operations to fight the coronavirus in February and early March as the White House sent mixed messages. Atlanta's Bottoms ordered the city's residents to stay at home on March 23. Gov. Kemp wrestled even longer with whether to impose a statewide shelter in place but did so on April 1.

THEN: The flu was already taking its toll on Northeastern metropolises like Boston and Philadelphia by the time Georgia officials sprung to action in October 1918.

Without public health bodies like the World Health Organization or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help issue guidelines – both were created in the aftermath of World War II – state and local governments had little national or international direction on how to act.

On Oct. 7, the U.S. surgeon general urged state health officers to consider social distancing. Georgia’s top health official at the time, T.F. Abercrombie, said localities should make their own decisions.

J.P. Kennedy, Atlanta’s health officer, moved quickly. That same day, he and the Atlanta Board of Health issued an order shutting down movie theaters, schools, churches, dance halls and pool and billiard halls for two months that was quickly replicated by the city council. All passenger vehicles, including trolleys, were directed to keep their windows open at all times unless there was a downpour, the Constitution reported the following morning.

Medical care

NOW: Scientists have urged people to avoid gatherings, stay at least six feet apart and, more recently, wear face masks in public. Hospitals across the nation, including Atlanta's Grady Memorial, have warned they're operating at or near capacity, and governors issued pleas for ventilators and protective equipment such as masks and gowns. Kemp announced April 12 the state would convert part of the sprawling Georgia World Congress Center into a makeshift 200-bed hospital and some hospitals have created more bed space in their parking lots.

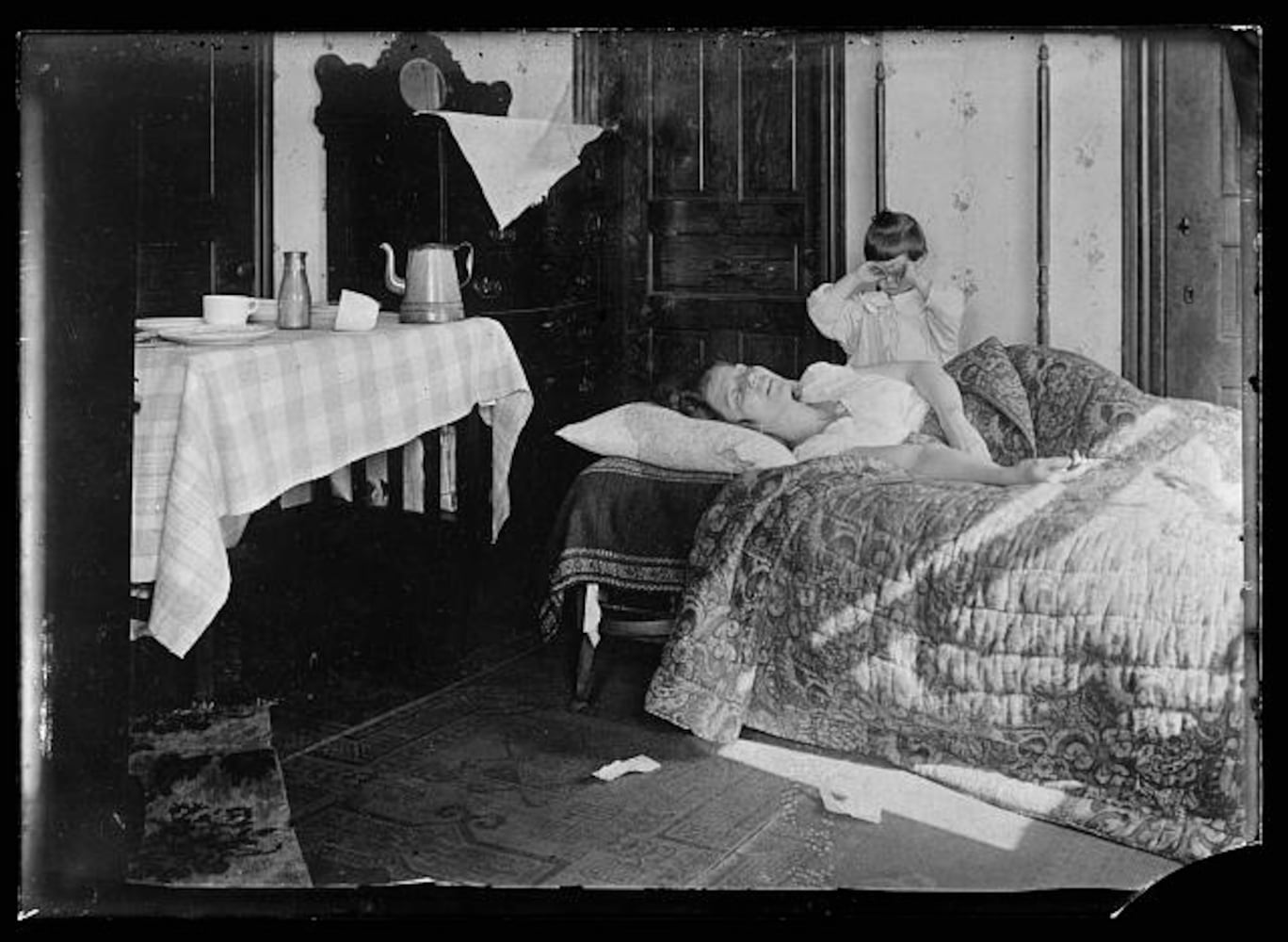

THEN: Doctors had a basic understanding of germs and the benefits of good hygiene. Georgians were urged to wash their hands, refrain from touching their face, observe proper coughing etiquette and stay home if they felt sick.

They also utilized quarantines and social distancing, although the latter was called “breaking the channels of communication,” according to Louise Shaw, curator of the CDC’s David J. Sencer Museum, and whose team has spent the last several years compiling an exhibit about the flu that will debut soon.

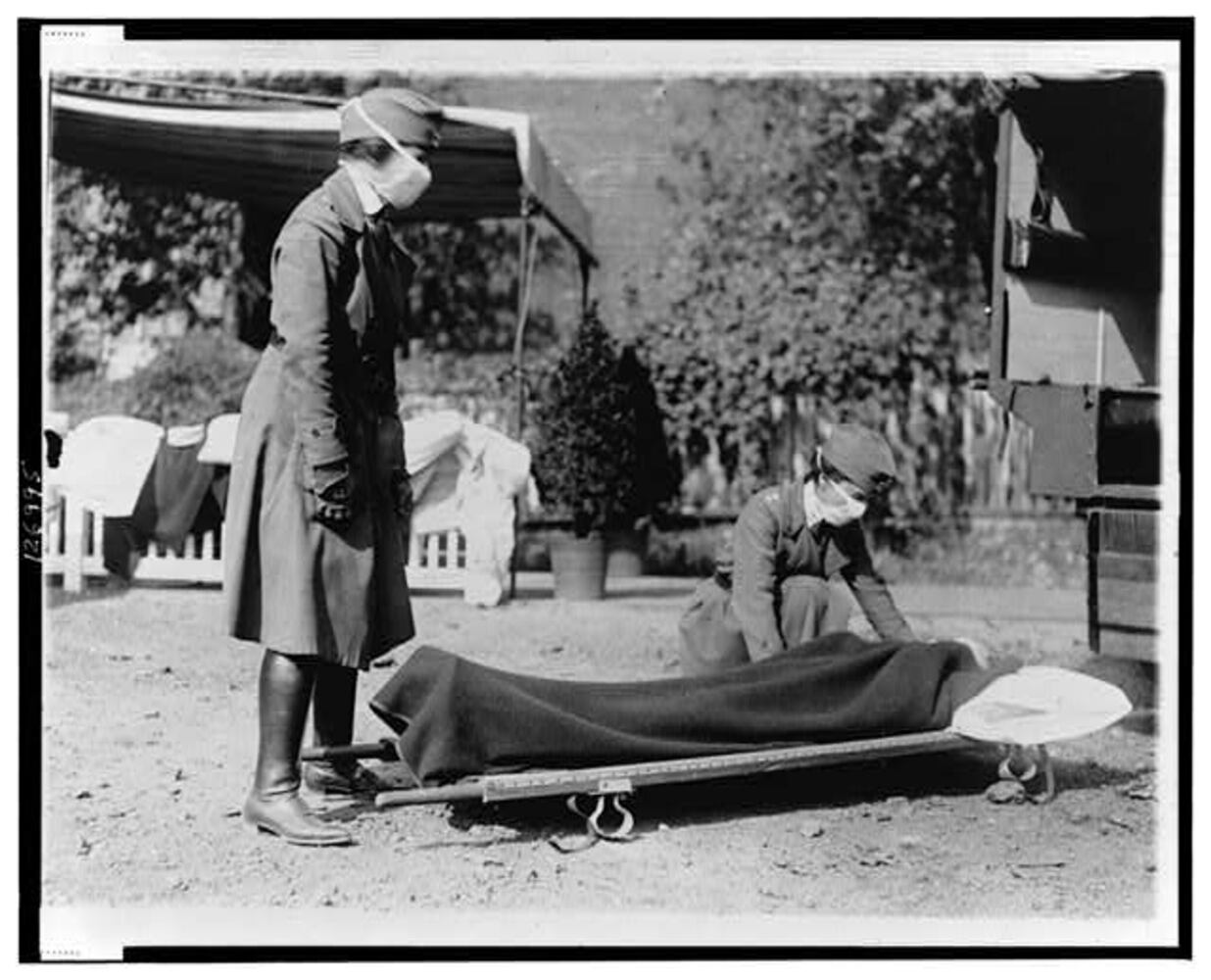

The state’s medical infrastructure was stretched thin by the war and the flu. Authorities set up makeshift field hospitals to help care for the influx of patients.

“They didn’t have mechanical ventilators or intensive care. Really all they could do was treat symptoms and try to make people comfortable,” said Deaton at the state historical society.

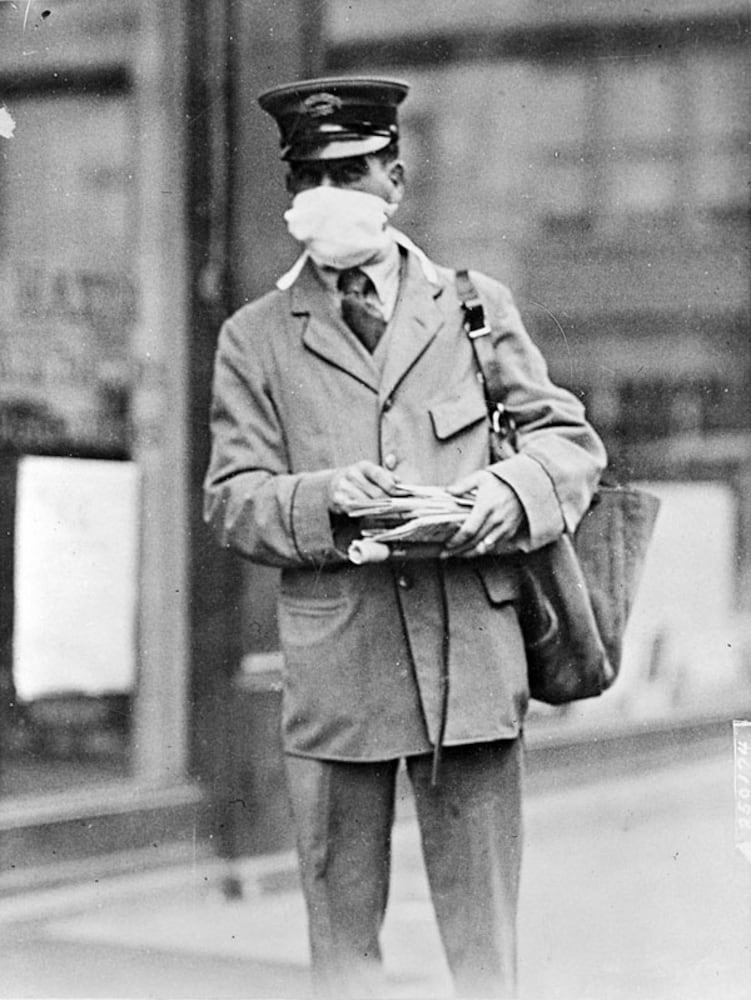

Personal protective equipment was in short supply. The Oct. 4, 1918 edition of the Constitution issued a call for female readers to make 100,000 influenza masks for Camp Gordon out of cheese cloths or similar materials. The local Red Cross opened work rooms for the women to gather and sew the masks. At the time, the organization blocked many African American women from volunteering, prompting some to organize their own efforts.

Without a vaccine to protect against the flu or antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, some Georgians relied on superstitions and folk remedies to help with the pain. Garlic and onions were common countryside treatments, and one Atlanta doctor had patients sprinkle sulphur in their shoes, according to Shaw.

The moment helped bring one regional product a national audience: Vick’s VapoRub. First developed by a pharmacist in North Carolina, it was a common treatment in the Southeast but saw its sales more than triple between 1918 and 1919.

Life in Georgia

NOW: With the exceptions of buying groceries and medicine, exercising and reporting to work at an "essential" business, Georgians have been directed not to leave their homes. Learning, work, social events and even worshipping have moved online, and concerts, sporting events and street fairs have been canceled.

THEN: Life was similarly turned on its head. Public transportation still continued via streetcars, but many trolley drivers refused to let passengers board who weren't wearing a mask.

Since fresh air was believed to help with the flu, some social activities were allowed to continue outdoors, including church services.

“The weather man promises to be kind and continue the present balmy, spring-like sunshine, and it is pointed out that the people not only will not be inconvenienced, but their health will actually be improved by gathering under the skies,” the Constitution reported on Oct. 12, 1918.

Atlanta officials allowed at least one major gathering to continue: the Southeastern Lakewood Fair. But visitors had to wear masks, prompting the Constitution to declare the event would look like a “great harem.”

“Think of the woman whose teeth fail to fit — she may be beautiful in a mask; think of the man whose wife knocked out a few of his front teeth — he may be handsome once again, in a mask,” posited an Oct. 15, 1918 front-page article about the fair.

Upwards of 20,000 people were drawn to the event, which featured bands, circus acts, horse races, fireworks and movie stars like Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford, according to the University of Michigan.

Lifting restrictions

NOW: Kemp has not said when he'll lift his shelter-in-place order, which he recently extended through the end of April. President Donald Trump and some Cabinet-level officials have called for an end to some restrictions by May to cut down on economic harms, but many public health officials say lockdowns will likely be needed for longer to halt the virus's spread.

THEN: By mid-October 1918, Atlanta's theater owners were beginning to chafe against restrictions, especially after officials allowed the Southeastern fair to move forward.

“There was push-pull between the medical establishment, the city and businesses,” Shaw said.

Some Atlanta officials, including Mayor Asa Candler, began suggesting the worst was behind. On Oct. 25, less than three weeks after the two-month closures were mandated, Candler announced a special session of the city council, which opted to overrule the Atlanta Board of Health and allow public gatherings to resume.

New flu cases declined for a while before spiking around Thanksgiving and through the winter, but health officials decided not to approve a new set of sweeping restrictions.

The Spanish flu killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including 675,000 in the U.S., according to the CDC. Atlanta appeared to walk away in better shape than many other American cities. Citing Census Bureau figures, the University of Michigan said 829 Atlantans died of the flu through February 1919.

Many experts believe Atlanta undercounted its death rates. Reporting was spotty and there wasn’t a test for the flu.

Timothy Crimmins, a Georgia State University history professor, said there’s another reason the city likely under-reported its flu rates: it was trying to lure businesses to the region.

“Atlanta promoted itself as a healthy city that wasn’t susceptible to the yellow fever that devastated coastal cities in the South,” he said.

Crimmins believes two factors did tamp down the region’s infection rates: light rainfall and the military’s demand for hydroelectric power generated from a dam on the Tallulah River. That led to brown-outs in Atlanta and forced movie theaters, the streetcar system and others to cut back operations even after they were reopened.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured