Democrats aim for suburbs in Alabama ahead of Deep South votes

Amanda Wilson has watched with a mix of glee and uncertainty as the imposing homes along this wealthy suburban town’s zigzagging streets has suddenly sprouted Democratic signs.

“I’m a blue dot in a big red state,” said Wilson, a 64-year-old retiree. “But I don’t feel as lonely anymore.”

Republican U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore’s struggles have transformed Alabama’s conservative-leaning suburbs into the latest political battleground, and Democrats are racing to establish a toehold in affluent communities such as this one ahead of big votes next year in Georgia and across the Deep South.

Fresh off victories in Virginia and a trio of surprising wins in legislative races in Georgia, Democrats are now set on a prize that was nearly unfathomable in a state Donald Trump carried by nearly 30 points: flipping a Republican-held seat in Alabama, which hasn’t elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 25 years.

Moore had already alienated some voters with his outspoken conservative views and his two ousters from the Alabama Supreme Court. But a spate of sexual misconduct allegations from women claiming Moore pursued them when they were teenagers and he was in his 30s has put Alabama Republicans on the defensive.

“He’s being unjustly lynched by ideological enemies,” said Elizabeth Johnston, a conservative activist and friend of Moore’s for 15 years. “Alabamans — they smell a rat. They know their favorite judge has been ousted more than once because he’s not a yes man. He’ll always stay true to their principles.”

Even as conservatives rally around Moore, who calls the claims “scurrilous,” his Democratic opponent, Doug Jones, is making a beeline for GOP turf. Jones has centered his low-key campaign on connecting with conservatives in places such as Mountain Brook, trying to woo voters who haven’t voted for a Democrat in decades.

Still, even as the polls tighten, the odds are daunting. About one-third of Alabama's voters are white evangelicals — a bloc that overwhelmingly supports Republicans — and 4 in 10 Alabama residents live in conservative-leaning rural areas.

Moore’s last race for public office, the 2012 vote for Alabama Supreme Court chief justice, offers a reminder of the steep electoral challenge. About 200,000 Republican voters cast ballots for Democrat Bob Vance in that vote, but Moore still won by 75,000 votes. Making up that deficit won’t be easy in a lower-turnout special election.

“Where do you find those people? I just don’t know. I thought digital targeting was the answer. It wasn’t,” said David Mowery, the Montgomery consultant who helped run Vance’s 2012 campaign. “There are votes in the suburbs, but are there enough of them? I just don’t know.”

‘I just can’t do it’

The suburbs of Alabama don’t have the kind of sway they do in Georgia, where about half of the state’s roughly 10 million residents live in metro Atlanta. Still, Alabama’s eight most populous counties account for as much population as the other 59 counties combined.

And Moore struggled mightily in some suburbs of those densely populated areas. He lost the counties surrounding Birmingham and Huntsville to incumbent U.S. Sen. Luther Strange in the September GOP primary, relying instead on a wave of rural support elsewhere to easily win the nomination.

Jones has kept the national Democratic Party at arm’s length as he takes aim straight for the hearts of wavering conservatives. His latest ad underscores his message: It features a string of older white voters voicing their support for him — and no mention of the word “Democrat.”

“I’m a lifelong Republican, but I just can’t do it,” one voter says. “I can’t vote for Roy Moore,” another adds.

They might as well have been speaking to Marc Labovitz, a 36-year-old who admits he once rarely looked across the ballot. After all, he was in middle school the last time an Alabama Democrat was elected to the U.S. Senate. This race, he said, “is the first time in my adult life where there’s a viable candidate on each side.”

And he’s made up his mind: He planted a Jones sign on his lawn.

“We don’t like feeling like we are a punchline. We don’t want to be embarrassed. We’re tired of being on Jimmy Kimmel every night,” said Labovitz, an executive at a family-owned steel firm in Montgomery. “We want to be a state that’s proud of our senator. And Jones will make us proud.”

In the working-class suburb of Trussville, where a string of boarded-up shops shares space with fancy retail outlets, Dave Honeycutt is a reminder of Moore’s deep well of support a bit farther outside city limits. The 53-year-old owner of a home security firm scoffed at the claims against Moore and predicted a blowout victory.

“Where have these women been for 40 years? I’m not sure where I was 40 years ago, but I’m sure fornication had something to do with it. And what about Bill Clinton?” he asked. “I’m voting for Moore. And everyone I know is, too.”

Barbara Cady wrestles with the same concerns as her relatives and friends in north Alabama. She’s optimistic that this campaign is energizing some of them, particularly women, to give Democrats another look. And she bubbles with frustration over the allegations against Moore. But she’s keeping her hopes in check.

“Something like this should galvanize voters. But I’m not sure,” said Cady, a speech pathology professor at Alabama A&M University. “Changing belief systems is not easy, and that’s what Democrats are trying to do. It almost has to hit home, to each and every one of his supporters, to change the debate.”

She’s certainly not shying away from the Democratic label: Her suburban Huntsville home sports a sign proclaiming her to be a Yellow Dog Democrat; her front porch and her car are adorned with Jones placards.

Some of those lifelong Republicans might just sit out the race. Turnout in special elections is notoriously hard to predict, and the lack of other statewide Republicans on the Dec. 12 ballot may entice some conservatives to skip the vote without feeling like they are abandoning their party.

Jimmy Brittain, a part-time truck driver who lives outside of Birmingham, seems ready to wash his hands of the race.

“The whole thing is an embarrassment to our state. I don’t know if he’s guilty or not, and I still believe in the presumption of innocence until proven otherwise,” said Brittain, 68. “But I’m just going to wait and see. This whole thing is a cluster.”

‘Not going anywhere’

Jones’ path to victory hinges on more than wooing over college-educated white voters in the suburbs. It also requires driving up the state’s African-American vote — about one-quarter of Alabama’s electorate — and cutting his margins of defeat in the arc of rural counties that Moore won by landslides.

“Democrats always get swamped in rural areas, but this problem goes to his core branding as a Christian conservative,” said John Anzalone, a Montgomery pollster whose firm has worked for Barack Obama. “This collapse of Moore goes deeper. Alabamans aren’t just outraged in the suburbs — you’ll see it everywhere.”

A Fox News poll released shortly after The Washington Post first reported allegations that Moore had initiated sexual contact with a 14-year-old girl in 1979 hinted at the Republican's struggles with some religious conservatives. The poll found that evangelicals still overwhelmingly support Moore, but that Jones had cut his advantage by 5 points.

And Jones also must steer clear of the national Democratic Party and its tarnished brand in Alabama. Jones’ campaign is heavy on his biography, particularly his role in prosecuting two Ku Klux Klan members who bombed a Birmingham church in 1963, and it relies on little public help from high-profile figures. U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia is one of the few outsiders to campaign for him in Alabama.

Local operatives can’t help but see similarities to Democrat Jon Ossoff’s unsuccessful campaign for Georgia’s 6th Congressional District seat, a stretch of suburban territory north of Atlanta where Republicans have also long held sway. Trump only narrowly carried the Georgia district, though previous Republicans had won by huge Alabama-like margins.

Ossoff also kept national Democrats at arm’s length, though the flood of money and volunteers from liberals in the Georgia race helped energize Republicans. Alabama Democrats have made a point of asking national Democrats to steer clear of the race.

“The suburban element is now key for both parties,” said Zac McCrary, a Montgomery political operative who also worked on Ossoff’s bid. “Democrats and Republicans in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia — they all need to reach voters in the suburbs.”

Moore has zeroed in on his rural base as he tries to refocus his campaign away from the allegations. The Republican has slammed Jones’ support for abortion rights as an “outrageously extreme position” and criticized his backing of same-sex marriage, both popular issues among the party’s conservative supporters.

“After forty-something years of fighting this battle, I’m now facing allegations, and that’s all the press want to talk about,” Moore said at a stop early last week in Jackson, a town of about 5,000 in southeast Alabama. “I want to talk about the issues. I want to talk about where this country’s going. And if we don’t come back to God, we’re not going anywhere.”

A ‘different’ vote?

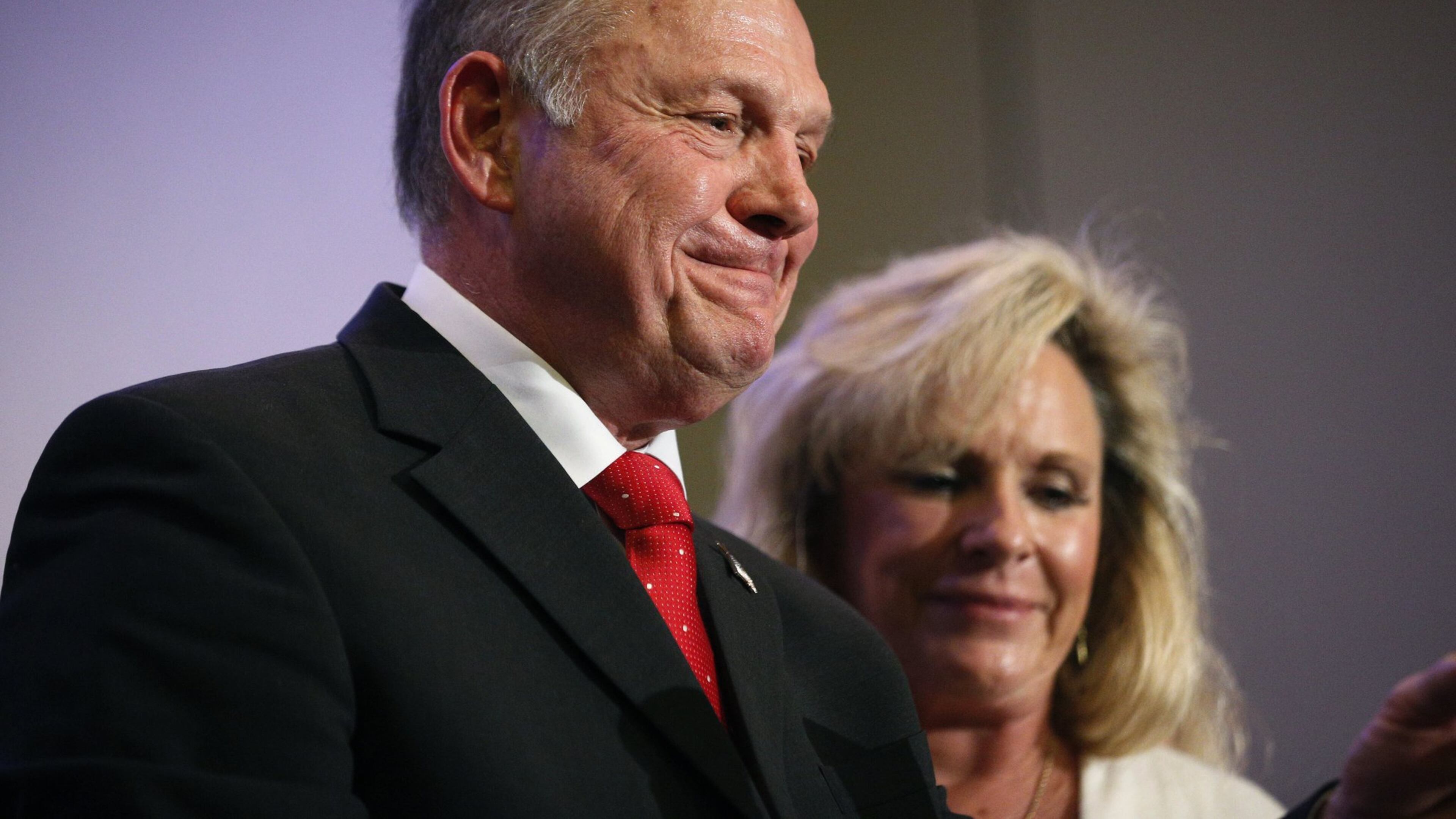

A few days later, about a dozen conservative activists and clergy members gathered at a Birmingham hotel as Moore watched from the front row to relay the same message: Moore was unfairly targeted by defenders of the status quo who manufactured false claims with the help of a complicit media to try to force him out of the race.

When one speaker asked a room full of supporters to raise their hands if any thought he would drop out of the contest, laughter erupted when not a single arm went up. Janet Porter, a friend and supporter of Moore’s who organized the event, presented the vote as nothing short of a battle against “the enemies of faith and liberty.”

“If the left can try to assassinate the character of Roy Moore,” she said, “then none of us are safe.”

And Moore, again, defied calls from a growing number of Republican leaders to step aside, singling out U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

“This is an effort by Mitch McConnell and his cronies to steal this election from the people of Alabama, and they will not stand for it,” Moore said.

Watching from the audience at that event was Brant Frost V, the chairman of the Coweta County GOP who had trekked from Georgia to lend Moore his help. He came armed with a Georgia analogy centering on former state Sen. Vincent Fort, a liberal Democrat who won sweeping victories in the state Senate for two decades.

“What would it take to get a Fort Democrat to vote for a Republican who got his picture taken with Richard Spencer?” he asked, citing the white nationalist. “Because that’s what it’s like to get your average Republican voter in Alabama to vote for Jones. And that’s why Jones won’t win.”

And some Alabama Republicans, too, are cautioning against a panic even as several public polls show Jones with the upper hand. The RealClear Politics poll of polls shows the race is deadlocked.

Brent Buchanan, a GOP political consultant, said Moore will inevitably struggle in some suburban areas that Republicans once easily carried. But that won’t make up for Moore’s wall of support across the deep-red rural spine of Alabama, he said.

“Polling that I trust shows Moore is still ahead,” he said. “I feel that will hold through Election Day because these allegations are solidifying his support among the base.”

Jones’ backers hope Moore is lulled into a false sense of security.

“If you had asked me if Jones had a chance a few weeks ago, I’d say he didn’t have a chance,” Labovitz said. “But this is serious. And this election is different.”

More Stories

The Latest