Finding meaning, one death at a time

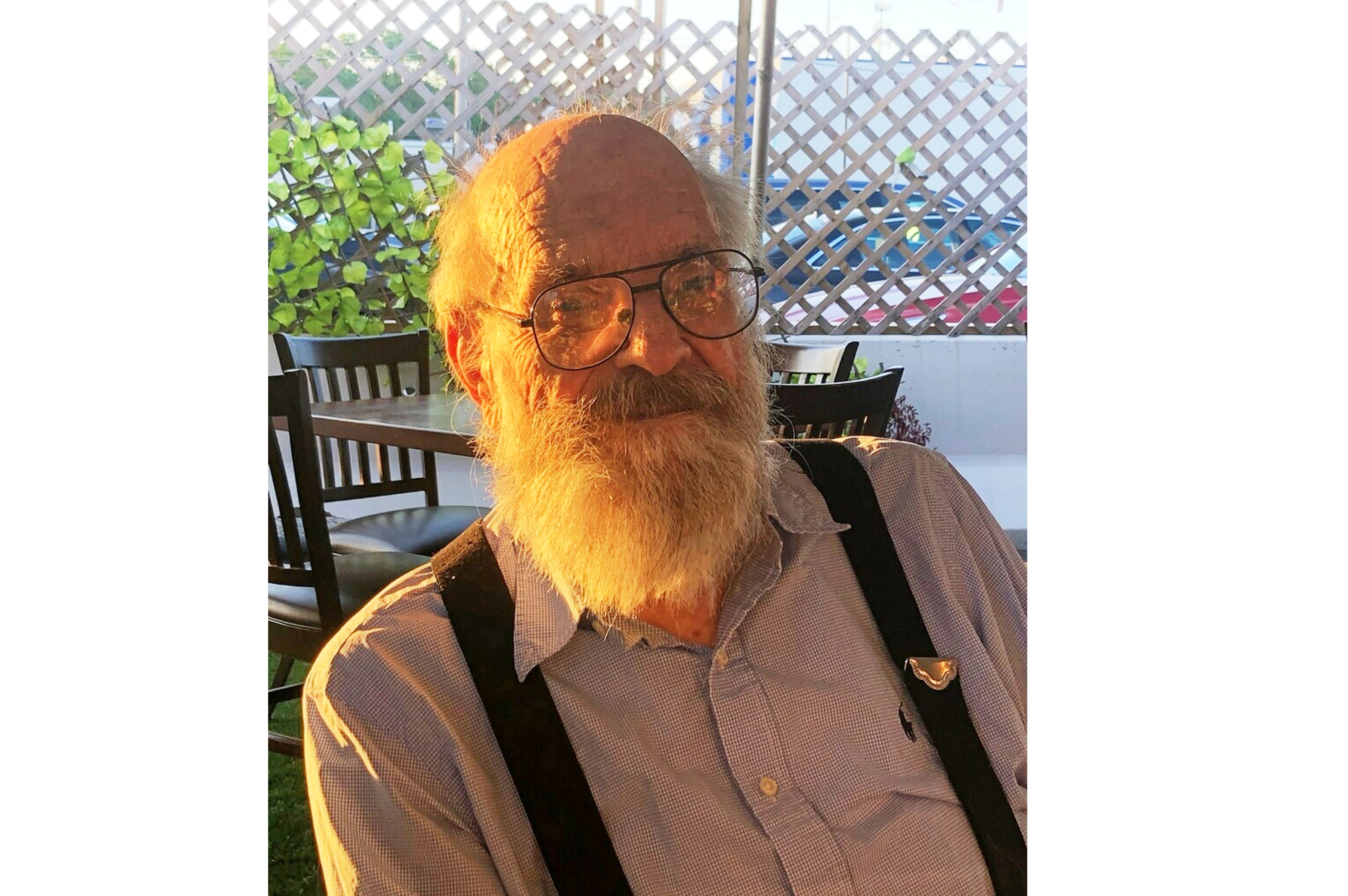

I often say my writer’s voice is my mother tongue for that is where I first heard my own stories: in my mother’s mouth. And this past month, which brought my mother’s passing and the heart-breaking spiral of death in Haiti, has taught me how valuable that gift of language has been.

My mother, Nellie M. McElroy, until the day she died, had a facility with language. Once when I was a child, my beautiful mother made an ugly face and told me she couldn’t “bear to eat oatmeal” because, “It multiplies in my mouth.”

She would constantly throw off goodies like that without batting an eyelash. And I, the baby of the family, the youngest of five, just soaked it up.

Southern stories, superstitions, black folks’ pronunciations, family lore flowed from my mother to me. Without all those seeds she sowed in my life, my mind, my heart, my memory, I could never have written my own novels. Without her generous sharing of truth, I never would have known that all the human beings in all the families in the world were alike in some ways. How else could I write universal stories about families?

My mother not only had a way with language and stories. She also loved reading that language and those stories. She was enthralled with stories, seduced by words, captured by books.

One of the first memories I have of my mother is of her sitting in her pink reading chair in the living room with a hard book in her hand.

At age 5 or so, I’d come running up to show her something I’d found out in the yard.

She would stop, look me in the face and say softly yet sternly, “Not now, baby, Mama’s reading.” Then, she would go back to her book.

I would stomp off for a couple of minutes, probably seconds, and return with the same request, “Hey, Mama, look at this leaf I found. Smell it!”

She would put the book down in her lap again, her manicured finger holding her page, and patiently repeat her rule.

“Not now, baby. Mama’s reading.”

And I would storm off wondering what magic was there in between the pages of those books. Because of my mother, I soon discovered that magic.

My mother not only cherished books and stories and tales and wisdom. She taught me to do the same. Not by telling me, but by showing me. One of her favorite sayings was, “You can show a Negro quicker than you can tell ’em.”

And she did. She showed and taught me by example. She had books she was reading all over the house. Books by her reading chair. Books in the bathroom. Books on her bedside table. Books on the screen porch by the rocking chairs.

And my mother taught me and my siblings the importance of reading good books and engaging stories with the power of her purse. For Christmas, birthdays, summer vacation, road trips my mother bought us the usual toys, shorts sets, underwear, socks and games. However, there were also always gifts of books mixed in with the other goodies and staples. In the 1950s, my mother introduced us to the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew and James Weldon Johnson poetry. In the ’60s, she shared her own books with us and we with her: James Baldwin, John O’Hara, Maya Angelou, Mario Puzo.

My mother fed us wonderful books in just the way she fed us fried Silver Queen corn in summer and chitlins and rich vegetable soup in winter.

This sharing of books was our family practice initiated by my mother until her death. Just weeks ago, one of Mama’s granddaughters shared the memoir of Diahann Carroll with her, and they discussed it over the phone.

Now, I sit and look at the heart-breaking pictures from Haiti and feel for each of the human beings, not one untouched by the natural disaster, who are experiencing true deep loss. I see the bodies lined up on the side of the roads, a soiled white shirt draped over the tiny lifeless body of a dear child. And although my own mother died in a modern anticeptic hospital and was lovingly cared for at the premier African-American funeral home in her community in Macon, I feel a connection with every one of those Haitians kneeling in the rubble moaning over the broken corpses of their loved ones and neighbors, then dragging sticks and shovels to the graveyard to dig holes for them.

Seeing these images at this time has shown me a stunning truth: Suffering, mourning, grief, loss are all universal experiences, yet they are all also personal and specific experiences as well. I realize that this is a dictum I have learned from writing: Write universally so every reader recognizes and understands your story. At the same time, create stories that are so specific that readers are drawn into a world that is unique and surprising.

Between phone calls to Mama’s parish for nearly 70 years concerning the prayers of the faithful for her memorial service, I read the predictions that put the death toll in Haiti at 50,000, a number that has since swelled to maybe 150,000. Perhaps, because of the confluence of my mother’s death and the Caribbean earthquake, for the first time I understand both the global impact of so many human beings — wayfarers on this planet with me — perishing at once and the specific pain of one individual losing another.

My mother gave me words. My writing taught compassion. My mother died. Tens of thousands of Haitians are killed. And, because of my mother, I know how it feels to mourn for all of them and for each of them. Universally and specifically.

Tina McElroy Ansa, a novelist, lives in St. Simons.