The NFL’s tentative $765 million settlement over concussion-related brain injuries was deemed inadequate by several former NFL and Atlanta Falcons players involved in the litigation.

In addition to the money, the league agreed to compensate victims and pay for medical exams and research. With the 2013 regular season set to start, a federal judge announced the agreement, which covers 18,000 players, on Thursday.

“It just doesn’t seem adequate enough for me, seeing that the NFL is projected to make between $12 (billion) and $18 billion in the future,” said Dorsey Levens, a former Georgia Tech star who went on to play in three Super Bowls over his 11-year NFL career.

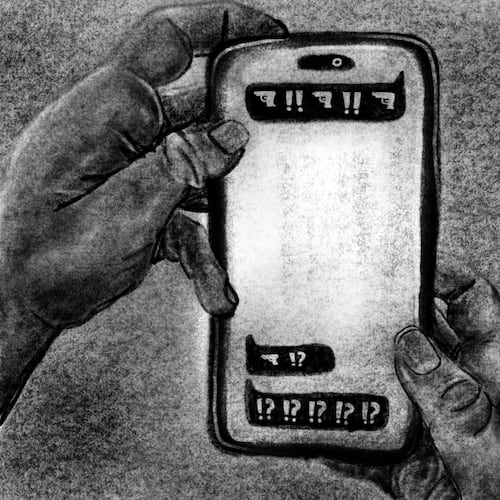

Kevin Mawae, a former National Football League Players Association president, tweeted: "NFL concussion lawsuit net outcome? Big loss for the players now and the future! Estimated NFL revenue by 2025 = $27 billion."

The class-action settlement, which is considered unprecedented by some sports law attorneys, is subject to approval by a federal judge. It came after two months of court-ordered mediation conducted by the Alternative Dispute Resolution Center in Newport Beach, Calif.

Levens, 43, who produced a documentary titled "Bell Rung," knows the pain first-hand from his collisions — he has black outs and memory lapses — and from the nearly 35 former players he has interviewed for the project at his Buckhead home.

One of the key terms of the settlement is that the agreement “cannot be considered an admission by the NFL of liability, or an admission that plaintiffs’ injuries were caused by football.”

In addition to wanting a more lucrative cash settlement, the lack-of-admission-of-liability clause doesn’t settle well with some former players.

“That’s a lot of money and that’s good, but it should have been more, with the possibility of letting the cat out of the bag so to speak,” said Levens, a plaintiff in the lawsuit. “Letting all of the information (about concussions) get out there. I think this is just a slap on the wrist.”

Gerald Riggs, 52, a star running back for the Falcons from 1982-88 and still the franchise's career rushing leader, said he was disappointed by the size of the settlement.

“I’m kind of shocked from the players’ standpoint that they settled for this,” said Riggs, a plaintiff in the case. “I think the NFL certainly could have done a lot more than that. … It’s kind of a drop in the bucket with the NFL and all the billions of dollars it makes.”

Riggs declined to discuss the effects a decade in the NFL had on him physically. After seven seasons with the Falcons, he played three years with the Washington Redskins.

He said he felt the league, which admitted no wrongdoing in the settlement agreement, was motivated by a desire to make the matter go away.

“The NFL is not going to say, ‘Guys, we botched some things, we did some things wrong.’ That will never be said,” Riggs said. “I think that’s the whole premise around this settlement: Give some money, make the whole thing go away, don’t say anything else about it.”

On Friday, a spokesman for the league said Commissioner Roger Goodell would not comment about the settlement. Falcons officials also declined to comment about the case.

“This agreement lets us help those who need it most and continue our work to make the game safer for current and future players,” said NFL Executive Vice President Jeffrey Pash. “Commissioner Goodell and every owner gave the legal team the same direction: do the right thing for the game and for the men who played it.”

Pash said that it was critical for the league to move on with helping the players, as opposed to spending millions more dollars and time fighting in court.

David Cornwell, an Atlanta-based sports attorney, also saw the settlement as “a very productive result.”

“When the cases were being filed, I thought that there was a substantial risk that the most money would be spent on legal fees and litigation costs and not on solving the problems for the guys who are suffering,” Cornwell said.

The league has taken several steps in recent years to eliminate helmet-to-helmet contact, they’ve expanded the definition of defenseless players and reduced the number of kickoff returns in the name of player safety.

Legal analysts see the league as the clear winner.

“They can move on from the general acrimony that existed between the former players and the league, said Timothy Liam Epstein, a professor of Sports Law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law. “It’s certainly a good deal for the league.”

There’s some validity to the contention that the league could have been exposed to a much higher damage award if the class action lawsuit went to trial.

“There were estimates that if this continued on past the discovery stages, there would be some potentially incriminating documents against the league that would push the value of the suit well over a billion dollars,” Epstein said.

For a former player in immediate need of help, the case has been termed a win. “The money is going to come to them a lot quicker,” Epstein said.

But for players such as former Falcons Ray Easterling and Shane Dronett, and NFL stars Junior Seau and Dave Duerson, the settlement is too late. They all committed violent suicides when the pain from alleged brain diseases took over their minds.

The rash of suicides led to the call for brain studies to determine the role chronic traumatic encephalophathy (CTE). It’s a condition thought to be triggered by repetitive head trauma or multiple concussions.

“I have seen players who were dying,” said Hall of Fame running back Eric Dickerson on ESPN’s SportsCenter. “Some guys could not afford health care at all,” said Dickerson, who was briefly with the Falcons in 1993.

Former Georgia State coach Bill Curry, who played in the NFL from 1965-74, has closely followed the case. He was not a plaintiff.

“It’s a very emotional subject for me. … Great friends like John Mackey and Larry Morris are no longer with us because of brain trauma possibly caused by football,” Curry said.

Kevin Turner, one of the lead plaintiffs in the lawsuit, also played for Curry when he was the coach at Alabama, and he has been diagnosed with ALS.

“All of those people are dear to me,” Curry said. “It’s too late for the first two, but Kevin seems to be encouraged.”

Ryan Stewart, 39, a former Georgia Tech star, played five seasons with the Detroit Lions. He was a plaintiff in the case.

“I’m pleased because there are a lot of people that are in some dire situations that didn’t have any help,” Stewart said. “They were being ignored and it was like they didn’t exist. Now, thanks to the settlement, the world knows about them and they’ll be able to get some assistance eventually.”

Stewart, who doesn’t plan to let his two sons play football, also wishes that the league had to present all of its information on concussions. As for his own history of injuries, Stewart said, “I know of about 10 to 15 (concussions) that I may have had. But now knowing what it actually is, I’m sure that I’ve got more.”

Jamie Dukes, 49, who played 10 seasons in the NFL and with the Falcons from 1986-93, believes the settlement is a starting point for change in the relationship between the league and its former players who helped build the billion-dollar empire.

“We’ve got players who are uninsurable, and they are dying because they are uninsurable, and they are having issues and challenges,” Dukes said. “Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of football players.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured