Historians and scholars assign monikers to historical figures.

Henry Clay, the first and only United States Congressman to be elected Speaker of the House of Representatives on his first day in the Lower Chamber (an accomplishment that was unprecedented, and, still, unsurpassed), is known as “The Great Compromiser” due to his deft handling and skill at negotiating agreements between ideologically opposite parties.

Ronald Reagan, the 40th President of the United States, whose speeches to the nation during moments of sadness and tumult, earned him recognition as “The Great Communicator.”

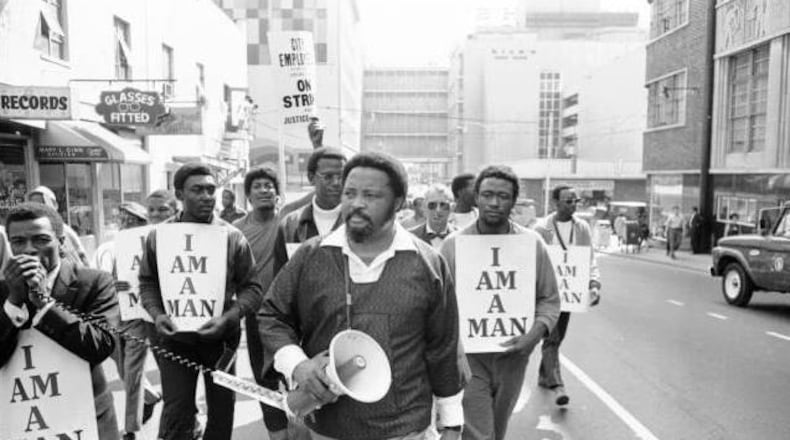

Hosea L. Williams, the bombastic, belligerent and barrel-chested field general in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent army, who relentlessly employed his arsenal of agitation in cities throughout this nation, was a complex non-conformist.

Credit: BOB DAUGHERTY

Credit: BOB DAUGHERTY

The campaigns he led in Savannah, St. Augustine, Selma, and Atlanta as an activist-legislator in the Georgia General Assembly, Atlanta City Council and the Dekalb County Commission, called for him to resist the temptation to play respectability politics. Hosea Williams was “The Great Defier.”

He defied what his civil rights brethren thought was logical or possible. He defied governors and future United States presidents. Williams even defied Martin Luther King Jr. when he refused to postpone the initial trek from Selma to Montgomery on Sunday, March 7, 1965. Conforming to King’s order would have invariably altered American history. “Bloody Sunday” does not happen if Williams follows King, his immediate supervisor’s, directive.

The title of my book, “Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest,” published by the University of South Carolina Press, is a contract with the reader.

Credit: University of South Carolina Press

Credit: University of South Carolina Press

Williams defied the odds assigned to him at birth. He was Black and born to blind, unwed parents in Attapulgus, Georgia, three years before The Great Depression.

As a teen, he defied the social mores in the Deep South by engaging in a sexual relationship with a white girl who was four years older than him. He was forced to leave town after the girl’s father had convened a mob to lynch young Hosea. He joined the United States Army shortly thereafter when he was 19 years old.

He defied death as a soldier in World War II, only to be beaten within inches of life by a white man over a cup of coffee upon returning home from the European Theater as a disabled veteran.

Williams’ education at Morris Brown College led to his enlightenment. After teaching chemistry in Conyers, he accepted a job as an analytical chemist in Savannah with the United States Department of Agriculture – one of the first Black chemists with the federal government below the Mason-Dixon. Williams and his wife Juanita enjoyed relative material comfort.

Williams thought that he was poised to live the proverbial American dream until he realized that he was the Bureau of Anemology and Plant Quarantine’s token Black employee.

The killing of an unarmed Black male by white police officers in Savannah thrust Williams into a life of civil rights activism.

He was henceforth completely committed to defying any entity or person that denied civil and voting rights to Blacks as an officer with the Savannah Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Scholars and some of Williams’ contemporaries recognized the old warhorse’s contributions to the Black freedom struggle. According to David Garrow, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference,” in the 1964-1965 timeframe, “Hosea was as valuable as anyone in SCLC to Dr. King because of his courage and willingness to lead dangerous demonstrations…People may remember Andy Young and John Lewis, but…Hosea was just as important to the movement.”

Credit: AP file

Credit: AP file

John Lewis, a founder of SNCC who participated in the Freedom Rides and marched shoulder-to-shoulder with Williams on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday,” called the fiery activist an authentic hero.

“Hosea Williams must be looked upon as one of the founding fathers of the new America,’’ he said. “Through his actions, he helped liberate all of us.”

Joseph Lowery, a founder of the SCLC and Williams’ former boss who fired him as Executive Director of the SCLC in 1979, portrayed the old warhorse of the movement as fearless. ‘’Hosea wasn’t afraid of Goliath,’’ he said. ‘’In fact, I was thinking about it, and I don’t think there was anything he was scared of.’’

None have lionized Williams in the same way as some of the aforementioned iconic activists.

Credit: University of South Carolina Press

Credit: University of South Carolina Press

Williams deserves recognition as a first-ballot Founding Father of a newer, better America. Lewis, Lowery and C.T. Vivian, towering timbers who fell during the last three years, were all awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama.

It is time for Williams to posthumously receive the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Rolundus R. Rice is the vice president for academic affairs at Rust College and the author of “Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured