Torpy at Large: When old crimes kill a new man’s career dreams

Benjamin Paul was thrilled by the opportunity Atlanta afforded. The single father was a career adviser at Miami Dade College and, in June, was offered a similar gig at Georgia Tech. It was a ticket to the big time in an ascendant city.

The $50,000 job was not only career advancement, it was a poignant tale of redemption. Paul, a drug-selling ruffian in his teens, had steadily toiled to turn his life around and prove he would not become just another young black man who fell off the rails early on and was unable to recapture a sense of purpose.

The job’s start date was Aug. 1, so Paul found an apartment in the gentrifying area around Howell Mill Road. It was near his job and, more importantly, would allow his third-grade daughter to attend a “winning school.”

Well, it didn’t work out that way. Earlier this month, Georgia Tech’s HR office sent him a letter saying thanks, but no thanks. A background check had disqualified him.

Never mind that Paul’s crimes — felonies that he had admitted to the university — were 12 years ago or earlier, occurring when he was 17 and 18. He is 30.

Never mind that Paul moved to Miami to escape bad influences in his native Tampa. Never mind that he worked to get a GED, an associate’s degree, a bachelor’s and finally a master’s. Or that he dutifully worked at Miami Dade College for four years and erased early suspicions to earn rave references from supervisors. Or that he’s an ordained minister. Or that he pieced together school, work and child care to raise a young daughter who is said to be a delight.

Paul admits his criminal record “looks real messy on paper.” The background check found convictions for sale of cocaine, being a delinquent in possession of a firearm, and two robberies (without a weapon).

He admits he sold small amounts of coke and “tried to shake down some junkies for cash. That didn’t go well.”

Paul served less than a year and then left Tampa. Getting a job is crucial for probationers to turn their lives around. It also proves to be difficult. He applied for entry-level jobs with Kroger, Target and UPS. But after background checks, the answer was nope, nope and nope.

He has noticed that companies increasingly perform background checks for most jobs. Atlanta employment lawyer Jeffrey Sand says, "That's become the norm. It's become cheaper to order background reports. You can get one for your babysitter."

Tech would not comment on Paul. The University System of Georgia’s hiring guide says schools “will consider the specific responsibilities of the position for which the candidate is being considered, the nature, number and gravity of crimes for which the candidate was convicted and the amount of time that has passed since the conviction.”

I suppose Tech, which otherwise hasn't been good about policing in-house shenanigans with administrators, wants another decade or two of Paul's good behavior to roll by.

» IN-DEPTH: Lax oversight allowed high-paid Georgia Tech officials to misuse tax money

» RELATED: Georgia Tech dragged its feet on investigation, tipster complained

» MORE: Georgia Tech president fires another administrator

After moving to Miami, Paul worked under-the-table jobs until he caught on with AmeriCorps, where he established a food pantry at Miami Dade College. Supervisors and co-workers liked his initiative and energy. He then told them about his past.

“I’ve done this 100 times; I’ve learned don’t bring it up until you have to,” he said.

Nathaniel Gomez, then a college supervisor, said several managers, including the dean, met to discuss Paul. They decided to keep him. By then, he had formed relationships and “had made a name as a positive, dedicated, professional employee,” Gomez said. Paul later got a couple of promotions.

“He earned everything he got,” said Gomez, one of his references to Tech. “He’s one of those people I could put my name out there for.”

Paul said, “Miami Dade College was my moment of redemption.”

After being allowed to stay, he said, “I gave them my best.”

But he was making just $30,000 and could only afford to live in a “hole-in-the-wall” efficiency apartment for him and his daughter.

“With the master’s degree (earned this summer) I had the confidence to venture out. I have experience. I have an education. Georgia Tech told me my references were stellar.”

But then his past, 12 years in the mirror, caught up with him. Again.

In recent years, society has increasingly pushed criminal justice reform after years of a tough-on-crime approach that has left offenders stacked up like cord wood.

Gov. Nathan Deal created the Council on Criminal Justice Reform to try to move thousands of Georgians from prison bunks into society as productive citizens.

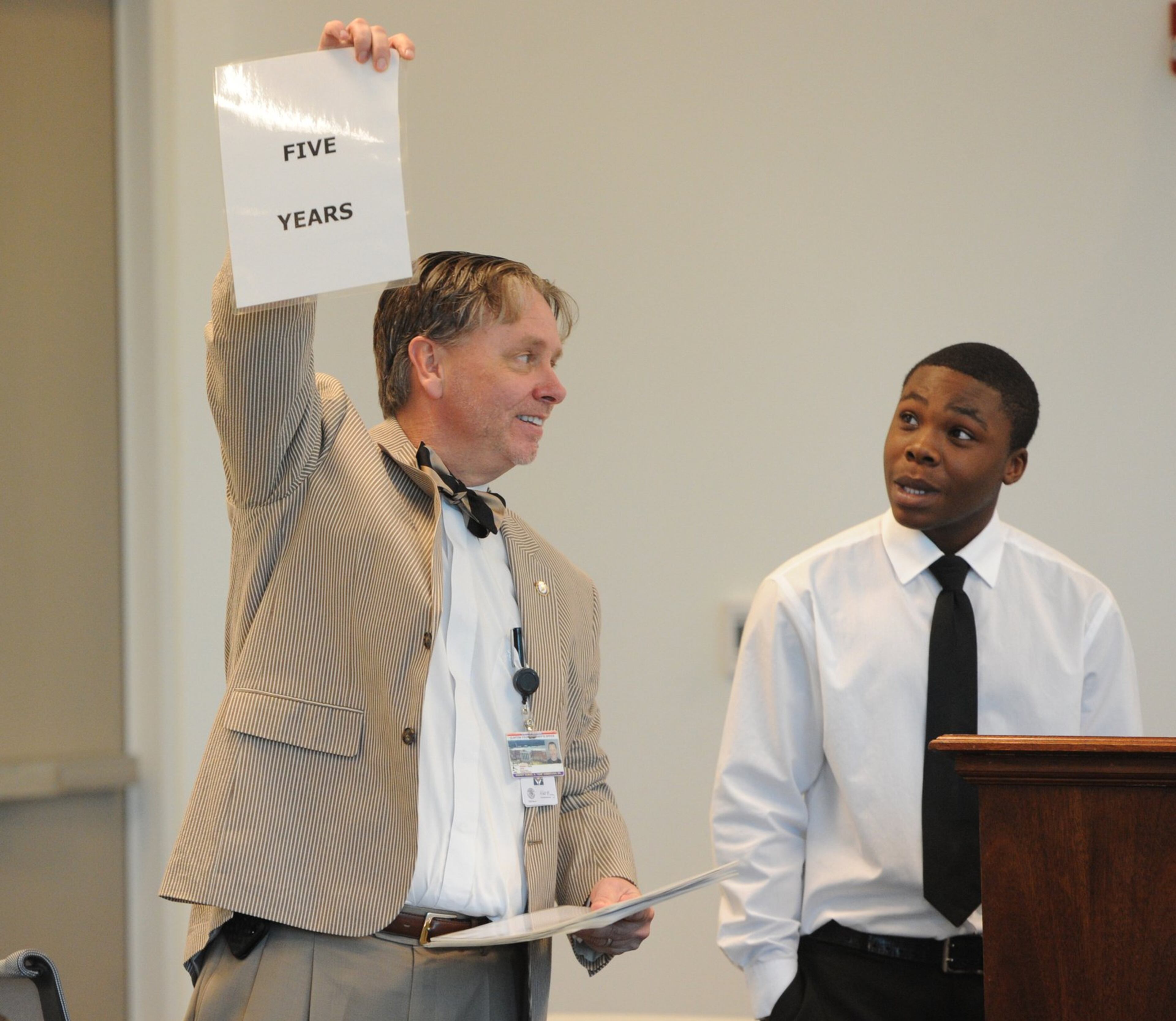

I reached out to Deal’s son, Jason, a Hall County judge who has been an advocate of drug court, which tries to find ways to give people second (and third) chances. When I called Jason Deal, he thought I was a drug court “graduate” he was trying to get enrolled in college.

He said cases such as Paul’s are not uncommon. “Unfortunately, I see that fairly often in drug court. They get a job and are working the job well, and after 30 days they do a background check and they lose the job. The company says, ‘Well, that’s the policy.’”

Steven Teske, chief juvenile court judge in Clayton County, said, “This creates a very heavy yoke around ex-offenders. And who it hurts most is people of color.”

Georgia is a “right to work state,” meaning companies largely have free rein to do as they please. Companies argue they want to know whether their employees are a threat to other employees. And they worry about liability.

“But at what point is it necessary to keep an ex-offender on a list?” asked Teske. “This guy for the last 12 years has lived an ideal life, but his name continues to be on a list that serves no purpose for society.

“What pisses me off,” Judge Teske said, “is many of the people (who are hard-liners concerning second chances) go to church and read the Scripture that says, ‘Forgive seven times 70 times.’ But they don’t live it. It’s hypocrisy.”

Maybe someone will give the teachings of the Good Book a shot for this man named Paul, who, like the Apostle Paul, has undergone a life change on a “street called Straight.”