Should state oversee handling of coal ash? Public gets its say now

Georgia is positioned to become the second state in the nation to assume oversight of how it disposes of its coal ash through a statewide permit program.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says a state management program, first approved in Oklahoma, puts decision-making in the hands of those who best understand local issues surrounding coal ash. But local environmentalists are concerned that state oversight could make it harder for citizens to hold utilities accountable and challenge plans that could have long-term consequences on human health and the environment.

The federal agency is holding public hearings Tuesday in Atlanta about the proposed state permit program.

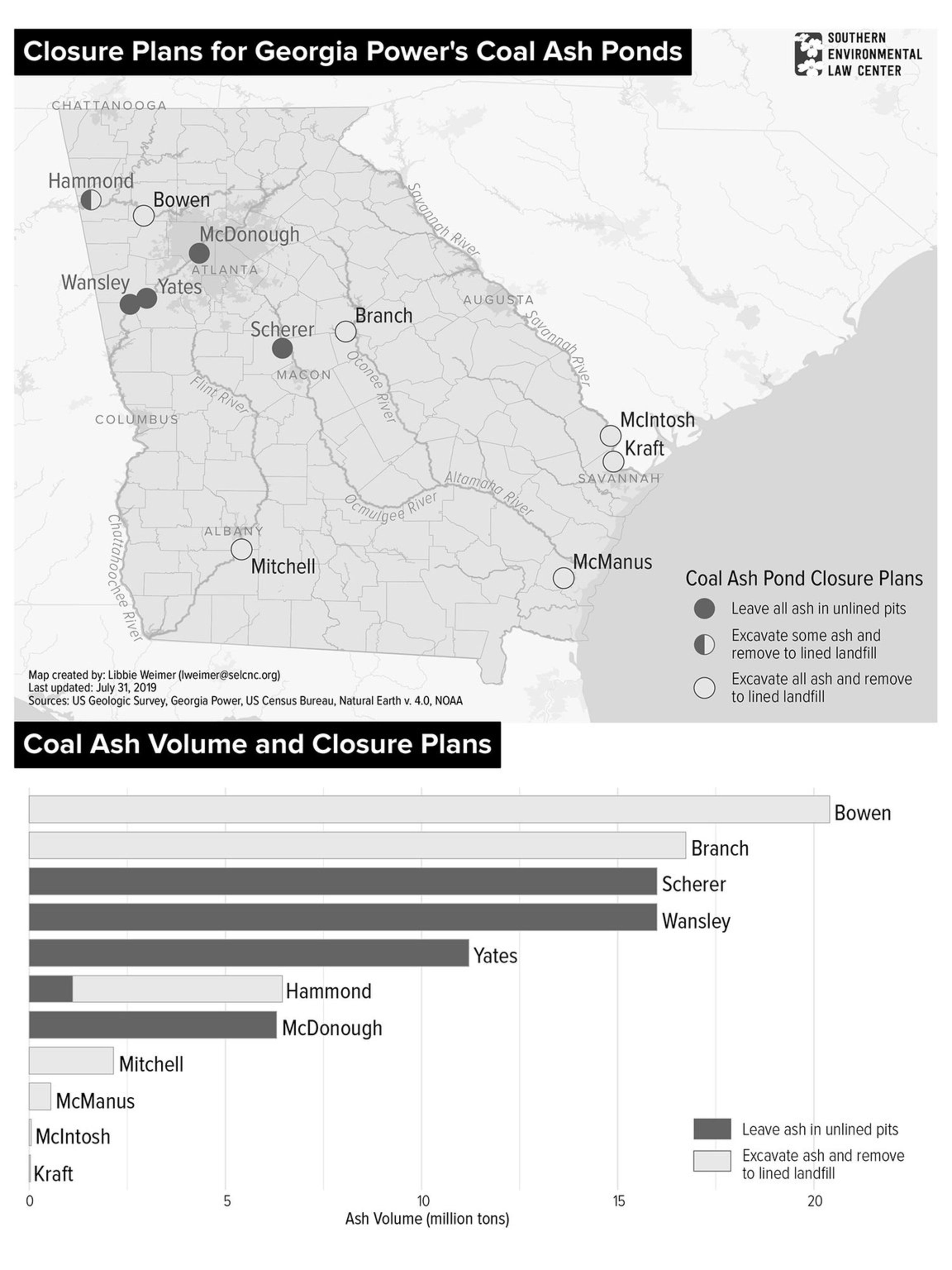

Georgia is one of the top coal ash-generating states, producing more than 6 million tons of coal ash each year. Most of Georgia’s coal ash has been generated by Georgia Power at 11 coal-fired power plants stretching from Rome on the north to Brunswick on the coast.

>> SEE MORE: Map of Georgia Coal Ash Ponds

Though the EPA treats coal ash as nonhazardous waste, it may contain arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury and other heavy metals that can be toxic to humans. It can leach into the environment if the ash ponds or landfills where ash is stored come in contact with groundwater, surface water or precipitation.

>> RELATED: Georgia Power coal ash ponds leaking toxins into groundwater

The federal government began regulating the disposal of coal ash after a 2014 spill dumped 39,000 tons of toxic coal ash into a North Carolina river. A year later, federal rules required unlined ash ponds and landfills to be closed in place or excavated.

The case for state permitting

In April 2018, the Georgia Environmental Protection Division applied for a state permit program. “A permit program is used because it provides for the direct oversight, review and approval of the utilities’ monitoring, closure and cleanup activities,” said Kevin Chambers, spokesman for EPD.

After EPD determines that an application meets requirements for siting, design, and operation standards, it will post a draft online with a 30-day public comment period. EPD reviews comments and makes any necessary changes before issuing a final permit, which then goes through the same process and may be subject to judicial review. Over time, if violations of the permit are identified, EPD would follow its standard enforcement policies, Chambers said.

With federal oversight, citizens can file a lawsuit to challenge how a utility is managing coal ash. With state permits, the process is not as straightforward.

“State control tends to tip the balance of power away from citizens who want to do some of their own oversight,” said Abel Russ, senior attorney at the Environmental Integrity Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for better enforcement of environmental laws. “The opportunity for ongoing enforcement of things like failure to post data required by the permit would be harder. The legal foundation for challenging those things is harder.”

>> READ MORE: Sierra Club says Georgia Power's coal ash plan illegal

Georgia Power is in the process of closing its 29 ash ponds, with plans to excavate 19 and close 10 in place, said Aaron Mitchell, general manager of environmental affairs for Georgia Power. Some plans for closing the ponds in place would leave the coal ash in unlined ash ponds.

Environmental advocates are most concerned about in-place closures that may impact groundwater. “Georgia groundwater and surface water do not belong to Georgia Power; they belong to Georgia citizens. New evidence confirms they are grossly polluting Georgia’s environment,” said Chris Bowers, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, which has used legal challenges to support the environment in the region.

Under state oversight, the problems could go unchecked, they say.

Challenges to coal ash disposal plans

In a letter released Monday, the Southern Environmental Law Center asked EPD to deny Georgia Power’s permit applications for in-place closures of coal ash ponds and landfills at five plants.

At Plant Scherer in Juliette and Plant Yates near Newnan, unlined coal ash ponds would lie within a 2-mile restricted area where unlined municipal solid waste landfills are prohibited by law, Bowers said.

At Plant Wansley near Carrollton, closure in place plans for one 343-acre pond would leave ash 80 feet deep in groundwater located on the floodplain of a former creek. Plant Hammond near Rome features a 25-acre landfill to be closed in place where decades earlier sinkholes were reported in the ground below.

And at Plant McDonough in Cobb County, a stream routed though a corrugated metal pipe would sit just 50 feet from an unlined coal ash storage area, potentially carrying coal ash pollution into the stream, the environmental group claims.

Georgia Power has said the closure plans meet the requirements of both state and federal laws. “We are being very aggressive in closing these ponds in safe ways,” said Mitchell of Georgia Power. “All of those details have been put into a package in an application for Georgia EPD to review. They are doing that now and will ask us to make changes.”

Mitchell said Georgia Power utilizes 500 groundwater monitoring wells across all of its power plants. “In limited cases, we have had detection of substances that we have been required to monitor, and we have elected on our own to go beyond the monitoring point to be sure we haven’t impacted anyone,” Mitchell said. “Based on the extensive data collected, the company has identified no risk to public health or drinking water.”

But citizens want to be sure their concerns are heard. “There should be a public process for permitting of these unlined coal ash pits,” said Rep. Mary Frances Williams, D-Marietta, who earlier this year introduced a resolution that called for liners in the ash ponds at Plant McDonough. “I think the only chance of doing anything about it is in the court of public opinion.”

PREVIEW

Public Hearing on Georgia’s Coal Combustion Residuals Permit Program

8 a.m.-noon; 1-3 p.m.; and 3:30-5:30 p.m. Tuesday, Aug. 6. Georgia Environmental Protection Division, Tradeport Training Room, 4244 International Parkway, Suite 116, Atlanta.

WHY IT MATTERS

In 2015, the U.S. federal government began regulating the disposal of coal ash after a spill in 2014 dumped 39,000 tons of toxic coal ash into a North Carolina river. Georgia Power announced the closure of all 29 of its coal ash ponds across 11 plants, but local environmentalists object to their plans to close 10 in place without a bottom liner, which could impact groundwater for years to come. Opponents of a state permit program say it could make it more difficult for citizens to challenge the company’s plans.