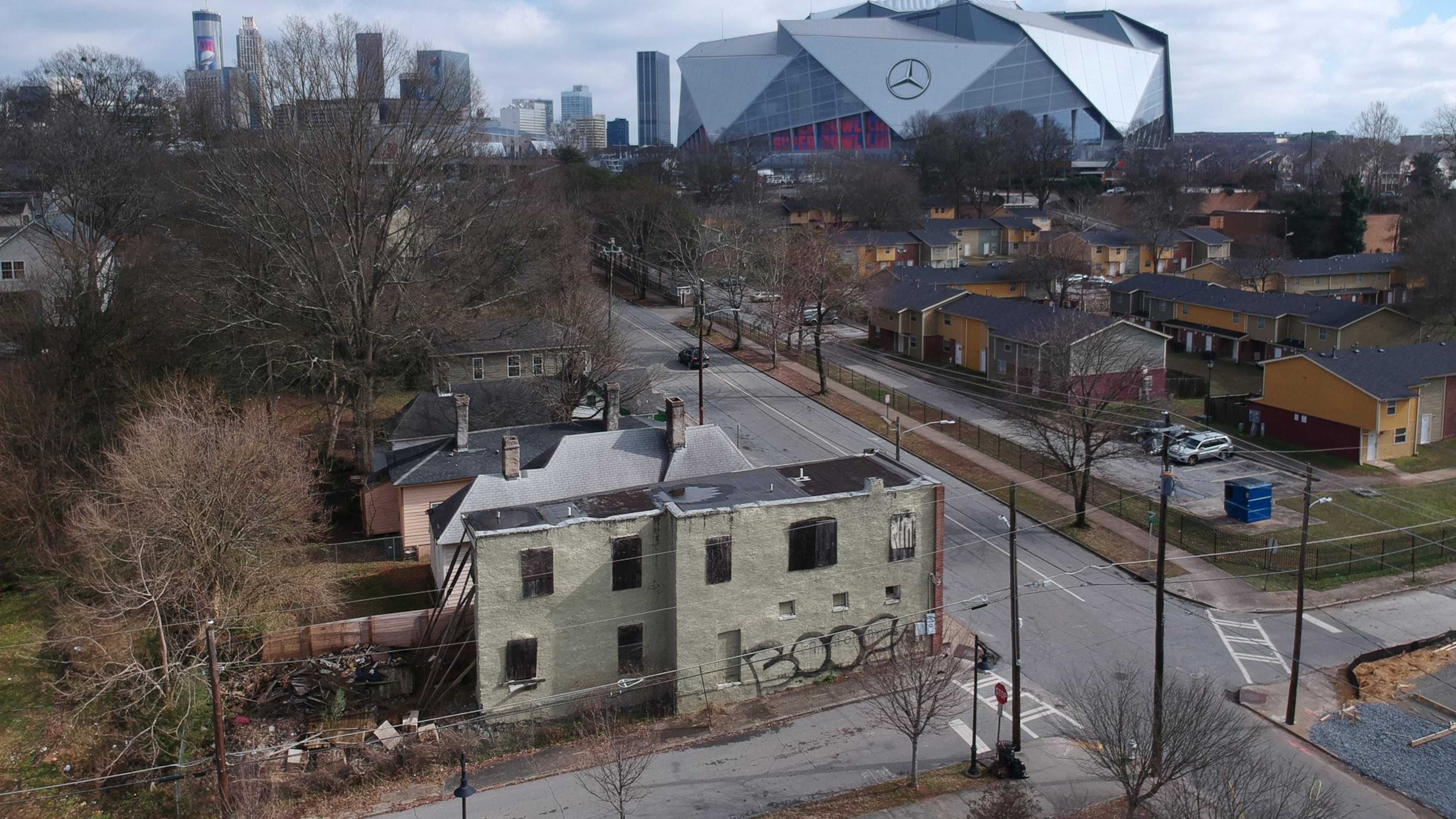

Old neighborhoods around Mercedes-Benz Stadium remain work in progress

Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank and city leaders made many promises in 2013 about what would become the $1.5 billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium, home to Sunday’s Super Bowl.

For $200 million in upfront public financing, and several hundred million more taxpayer dollars for upkeep for three decades, the new stadium would help Atlanta land the big game and keep the city competitive in the arms race for major events such as Final Fours and perhaps the World Cup. In exchange for the public money, Blank, the city and civic leaders also promised Mercedes-Benz would do what other arenas had failed to achieve in Atlanta — revitalize the largely poor and black neighborhoods around it.

When the New England Patriots and Los Angeles Rams face off in the first National Football League title matchup Atlanta has hosted since 2000, the stadium will have delivered on boosters’ Super Bowl promise. The Benz also has played host to a national college football title game and other marquee events, including Major League Soccer’s championship game last December, which drew more than 70,000 fans.

The effort to bring renewal to neighborhoods such as Vine City, English Avenue and Ashview Heights, however, remains a work in progress. Development pressure, from the mammoth mini-city in downtown’s Gulch to plans for mixed-use development along the Beltline’s Westside Trail, also has raised the specter of real-estate speculation pricing out the poor.

Rebuilding these historic but blighted communities — where the Georgia Dome, the Olympics and more than $100 million in grants failed to make much difference — is likely to be a two-decade effort, said Frank Fernandez, an executive with the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation who oversees Westside investments for the nonprofit.

Blank has committed $30 million and Invest Atlanta committed $15 million for neighborhood revitalization. Other federal, corporate and nonprofit grants have contributed tens of millions more.

Over the years, as the emerging black middle class left the city for the suburbs, the neighborhoods combined lost about two-thirds of their population from a peak of about 50,000 in the 1960s, when they were vibrant mixed-income communities and home to much of the city’s civil rights leadership, said John Ahmann, executive director of the Westside Future Fund. The Westside Future Fund is a nonprofit created by some of Atlanta’s biggest corporate titans and then-Mayor Kasim Reed to help steer revitalization in the stadium neighborhoods.

Real-estate speculation before the economic collapse and the foreclosure crisis that followed only worsened the effects of depopulation. English Avenue and Vine City, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. lived when he was assassinated in 1968, are dotted with abandoned and boarded-up homes. Drugs and crime are rampant.

But supporters point to collaboration between the Blank Foundation, the Chick-fil-A Foundation, the Westside Future Fund, the city and a host of other nonprofit groups that dwarf community improvement efforts that fizzled out during the 1980s and 1990s when the Georgia Dome was built.

They note early wins in workforce development, public safety and early childhood education. Crime, while still high, is down 43 percent in the past two years. Some 650 residents that received workforce training at the Blank-supported Westside Works have found full-time employment, and several hundred helped build Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

“We’ve really tried to use the stadium as a lever to connect people to jobs and economic opportunity,” Fernandez said.

Santecia Bynum, 30, has felt the excitement. Bynum grew up near the Atlanta University Center but moved away years ago. She was selected to purchase a Habitat for Humanity home and picked a lot on Parsons Street about a mile and a half west of the stadium. Some 40 volunteers, organized by Habitat and the Future Fund, scurried about with paint and power tools on a recent rainy Saturday inside the three-bedroom bungalow where Bynum will raise her 10-year-old daughter.

“People are coming together more, sticking together and being involved in the community,” Bynum said. “I see the gardens, the renovations, everything.” It wasn’t long ago that “people were scared to come by” but now there are Airbnbs, she added.

A federal-backed drug task force has helped reduce crime along with a grid of security cameras. The At-Promise Youth and Community Center, an Atlanta Police Foundation program along Cameron Madison Alexander Boulevard, is helping to get young people off the street.

In the meantime, a hot housing market and renewed real-estate speculation threatens to displace residents, many of whom are vulnerable seniors and working families who live well below the poverty line.

“We don’t have a lot of time,” Ahmann said.

On a recent drive through English Avenue, Ahmann said nonprofits and the city working on the Westside need to obtain more land to preserve affordability. Most residents of Vine City and English Avenue have incomes that can only support about $350 to $450 a month in rent, a class of affordability that is vanishing in Westside communities.

“Concentrated poverty doesn’t work,” Ahmann said. “But keeping people in place is our imperative.”

He said a mixed-income approach will be key to restoring Vine City and English Avenue and the Atlanta University Center area to what they once were.

The Westside Future Fund and its allies have acquired boarded-up homes and smaller apartment complexes. Some will be torn down and rebuilt. Others, like a pair of abandoned apartment buildings on James P. Brawley Drive, will be rehabilitated with the vast majority of units preserved as affordable for low-income residents.

Two Fridays each month, the Westside Future Fund holds gatherings to connect churches, nonprofits and business leaders and share community news. The room is packed each meeting with Westside residents and a who’s who of Atlanta business and philanthropic elite.

Developers, seeing signs of downtown’s vitality and tantalized by the western leg of the Atlanta Beltline, have pitched grand mixed-use projects, but that speculation is driving up prices. There’s buzz about a giant new public greenspace, Rodney Cook Sr. Park, that will honor Atlanta’s civil rights heroes and tackle flooding issues that have plagued parts of the community for decades.

The interest of developers and newcomers frightens many Westside residents, fearful they could be pushed out. Some point to city investments, such as a futuristic-looking pedestrian bridge that’s little used other than game days, as misplaced when buildings within sight of the glistening stadium are crumbling.

Crime remains a problem. Addicts often find their way into abandoned homes to get their fix.

Kelly Brown, who lives in English Avenue, started filming Westside Future Fund meetings a few years ago for neighbors who couldn’t attend. She said changes are happening in the community, but the risk of displacement is still high.

A neighbor recently lost the family home because of rising housing costs. Another family on her block could soon be displaced.

She credited Ahmann and the Westside Future Fund for being conscientious and trying to make inroads with the community. The nonprofit pays Brown to help with the time and cost of producing her videos for the neighborhood.

The promises made to help the Westside are being met but more needs to be done to help people addled with addiction to alcohol and drugs, she said. Rats from vacant homes still terrorize the community.

Last week, Brown said she found a white man in a pickup with a Gwinnett County tag trying to inject himself in the stomach with what she assumed was heroin.

“Yes, I do see change, and yes, I can see a positive influence,” she said. “But are any of us satisfied?”