Minute by minute in the Justin Ross Harris trial (Oct. 28)

This is a running account of the hot-car death trial of Justin Ross Harris, the Cobb County man accused of intentionally leaving his 22-month-old son, Cooper, to die in the back of Harris's SUV. The prosecution rested its case today after 15 days of testimony by 51 witnesses.

Lumpkin asks the judge to declare a mistrial, saying the prosecution has sought, in the presence of the jury, to shift the burden of proof from the state to the defense. Prosecutor Evans strongly asserts that the state knows where the burden of proof lies and denies the prosecution has engaged in "burden-shifting." Staley Clark, apparently without ruling on the motion for a mistrial, declares the court in recess for the week.

The jury comes back into the courtroom for brief re-cross by Evans. Lumpkin does an even briefer re-direct, and the witness is excused. There is a quick conference at the bench. "We have accomplished what is available to be accomplished for today," Staley Clark tells the jury. "It is Friday after all." She dismisses the jury and hears additional arguments about the motion to exclude testimony by Det. Shawn Murphy.

Jesse Evans rises to argue against the defense request that the judge reconsider her ruling on Murphy's testimony.

Lumpkin cites occasions on which Murphy made false statements on multiple warrant applications. Several of the applications contained variations of the statement that Harris had admitted to conducting web searches to learn about "child deaths inside vehicles and what temperature was needed for that to occur." Lumpkin reads these statements, which all proved to be untrue but were all used as grounds for obtaining the search warrants. "These," Lumpkin said, "(are) personal statements made by this witness (Murphy), under oath, to the magistrate."

He complains that these were actions taken directly by Det. Murphy but that the court, agreeing with prosecution motions, will not permit the defense to ask questions about it.

"We respectfully disagree with the ruling on legal grounds," he said, adding later: "This defendant has constitutional rights, and this court is in place to uphold those."

Back from the break. Defense attorney Bryan Lumpkin, outside the presence of the jury, explains in detail to the court what the defense wants to know from Det. Shawn Murphy.

Judge Staley Clark excuses the jury so the parties can argue about the admissibility of other testimony that Murphy might offer. She then declares a break in the proceeding.

Lumpkin's direct examination is frequently halted by Boring's objections, most of which the judge sustains. He returns to questions about items of evidence in the search warrants and asks the locations Murphy went to obtain those items. In addition to other locations he'd already testified about, Murphy says he went to the Kaiser Permanente office to fetch medical records on both Cooper and Ross Harris. Lumpkin wraps up his direct.

Lumpkin asks Murphy whether he saw Cooper's car seat, and Murphy says he did see it at the police department's evidence garage, where the vehicle had been taken for processing. Lumpkin asks him where the restraining straps were threaded into the car seat. Murphy says they were in the middle slot, but at the time he mistakenly informed Stoddard that the straps were threaded through the lowest level of the seat. This is important because it goes to the angle of the seat on the day Cooper died and how easy or difficult it would have been to see him in the car seat.

Murphy says he went to the Treehouse, the name of the Home Depot office building, and also to the Home Depot corporate offices, to serve search warrants. He then talks about his visit to the Harrises' home on June 30, 2014, to serve a search warrant. The warrant sought any financial records and also for the light bulbs Harris said he had bought at lunchtime on the day Cooper died. He said officers checked to see whether there were light bulbs burned out in the residence; that is, whether Harris had a reason to buy the light bulbs he bought that day. But he found that the light bulb in the master bathroom was burned out.

2:27 p.m.

Murphy says he and Stoddard interviewed several of Harris's co-workers of Harris at Home Depot -- those who worked closest by him. He described the cubicles there as having short walls that enabled workers to see one another. Lumpkin asks whether Murphy noticed any mementos or personal items in Harris's cubicle. Murphy says he can't remember.

Murphy prepared four search warrant applications at his computer and then transmitted them to a judge for approval. At that point, prosecutor Boring objects to three questions in a row, and Staley Clark sustains each objection. Murphy said the next day he and Stoddard went to the medical examiner's office for the autopsy of Cooper Harris and then went back to the office apply for more warrants. Lumpkin asks how many. Boring objects, and Staley Clark sustains it.

Murphy says he believes Harris arrived at police headquarters before he and Stoddard did. He later saw him on camera in an interrogation room: the detectives, he says, are equipped with software that enables them to watch or listen to what's happening in the interrogation room from their desks.

Murphy says Harris was sitting in a patrol car by the time he arrived on the scene. He didn't speak with Harris there, he says. Within an hour, he and Stoddard returned to headquarters, where Harris was taken. Murphy says he did not take part in the interrogation of Harris at HQ but instead began preparing search warrant applications for Harris's home, his car and his computers.

Bryan Lumpkin handles direct examination for the defense. Det. Murphy says he has been with the Cobb police for 10 years after working for the Atlanta Police Department for three years. He has been a detective in Cobb for about three years.

He was riding with Det. Phil Stoddard, following up on another case, when they received a call to report to Akers Mill Square shopping center. Says Stoddard was appointed lead detective that day, and Murphy was assigned as second. The two worked "hand in hand" for the most part, Murphy says.

Webb says his last communication from Harris was May 29, note quite three weeks before Cooper died.

Rodriguez on re-direct: "Mr. Webb, you wouldn't consider Ross a friend, would you?" "No, he was a client," Webb said.

He also says no one from the Cobb County police contacted him regarding Harris. Webb is excused as a witness, and the defense calls Det. Shawn Murphy.

Boring: "Were you aware of any problems he was having at work?"

Webb: "No, sir."

Boring: "Did you have any idea that he was looking for a new job that he didn't actually get in May?"

Webb: "No, sir."

Webb says his real estate firm sent emails to prospective customers, including Ross and Leanna Harris, every day. Boring asks whether Harris was looking for houses with hidden rooms. Webb says not to his knowledge.

2:00 p.m.

Prosecutor Chuck Boring handles the cross-examination for the prosecution. He asks Webb whether he knew anything about Harris's double life of sexting with multiple women. "If he had this other side of his personality, he obviously kept that hidden from you," Boring said. "He seemed very typical of any buyer who would come into the office."

Webb found a rental property for the Harrises that was owned by a friend of Webb's. He said Ross Harris's credit rating was superior and he thought he'd be a good tenant for his friend and a good prospect for buying a house down the road. After a time, he said, the couple also began looking in Kennesaw and Acworth because they could get "more house for the money" there than in East Cobb.

Webb is given a sheaf of emails and asked whether emails that were sent to him -- he says they are -- and are they an accurate depiction of the kinds of emails that passed between the two -- he says they are.

Webb says he met with Ross and Leanna in February 2014 to go over the areas of Cobb County the Harrises were interested in. He says the couple wanted to find something in East Cobb, because of the quality of the schools.

The jury returns, and the defense calls its first witness: he is Roger Webb, a real estate agent who said he was helping Ross and Leanna Harris to find a house in Cobb County. Defense attorney Carlos Rodriguez handles the direct examination. Webb says he communicated with Ross Harris primarily via email but also spoke with him on his cellphone.

Staley Clark responds: "I haven't told what you can ask him about. I have told you that I have not precluded you from calling him as a witness. That's up to you." She tells Lumpkin to call the witness if he wants and ask the questions he wants, and the court will decide whether the questions are appropriate and the answers admissible. The jury is not yet in the courtroom: motions in limine are heard outside the jury's presence. Staley Clark orders them back in.

Judge Mary Staley Clark denies the defense's request to lead the witness. She then asks the prosecution to argue its motion concerning the search warrants connected to Det. Murphy. Prosecutor Evans says Murphy's knowledge of the warrants and of the police interview of Harris is second-hand at best, and he has no standing to testify.

Staley Clark grants the prosecution motion to exclude Murphy's testimony. Lumpkin explains to the court what the defense wanted to ask the witness. Staley Clark says she did not preclude the defense from asking those questions; she said her ruling applies to questions to which Murphy's answers would be hearsay.

The defense's Bryan Lumpkin argues in favor of Det. Murphy's appearance as a defense witness. He asks that the court declare Murphy a hostile witness, enabling the defense to ask leading questions. Lumpkin says he wants to ask Murphy questions about the search warrants the detective helped to prepare and execute.

The court is back in session after lunch. The state rested its case before lunch, and now it's the defense's turn. But the prosecution has filed a motion "in limine" (LIMM-uh-nee) which is a request that the judge exclude certain testimony before it is given. The witness in question is Det. Shawn Murphy of the Cobb police. Prosecutor Jesse Evans doesn't want to see the defense put Murphy on the stand and is arguing against his appearance.

Defense attorney Maddox Kilgore moves for a directed verdict of acquittal on all counts, arguing that the state proved none of them beyond a reasonable doubt. But Kilgore reserves the argument. He tells the judge he will open his case this afternoon and expects to call two witnesses. Boring tells the judge he thinks she should deny the motion for a directed verdict.

Judge Staley Clark declares the trial in recess.

"At this time, your honor, the state rests," says prosecutor Chuck Boring. The judge sends the jury to lunch.

Rodriguez on re-cross. He has Dustin acknowledge that, before he looked around in the car in 2014, he already knew the male model (the doll) was in the car. The implication is that Dustin saw the doll because he already knew it was there. If Harris didn't know Cooper was in the car, he might not have seen his son, Rodriguez implies. He also refers to the "flyover" image of the SUV, which has no roof and no window glass, and asks whether that was an accurate depiction of the vehicle in reality. "It's just to show the spatial orientation of everything inside the vehicle," he said.

Prosecutor Jesse Evans on re-direct. He has Dustin put up another 2014 scan from the perspective of the driver's seat and then asks a rapid series of questions on which objects Dustin could see from that perspective when he actually sat in the car. Dustin says he could see the front passenger-side floorboard, the front passenger's seat and, on the periphery of his vision, the car seat and the head of the doll over the top of the seat. Now Evans has him project the 2016 scan and asks whether he can see each of those objects. He he says he can.

Rodriguez then points out that, when the image zooms in to the SUV's rear-view mirror, the doll used to depict Cooper is not visible. "When you're looking from your vantage point directly into the rear-view mirror, you can't see that doll, can you?" Rodriguez asks. "No, sir," Dustin replies.

Rodriguez then has Dustin change images to another panoramic view of the interior of the car that he created in 2014. Harris appears to be watching the proceeding and the scans intently. Dustin pans around the image, and Rodriguez begins to point out differences between scans that were made in 2014 and a new set that was made about two weeks ago. Rodriguez then asks Dustin who positioned the car seat in the second set of scans. It was not Stoddard but another detective, Grimstead.

At length, he elicits an acknowledgment from Dustin that Cooper's car seat was in one position during the first set of scans and in a different position in the second set of scans.

Dustin explains that he was the closest person on the scene at the time in height to Ross Harris. Dustin has testified that he is about 6-foot-3. So Stoddard used Dustin to model Harris in the front seat of the SUV. This was done as part of the scanning process to establish Harris's sight line if he were sitting in the driver's seat. Rodriguez then asks him to display the panoramic image from 2014.

Rodriguez supplies Dustin's report from 2014 regarding the scans and asks him to look up which detective placed the car seat. Dustin spends quite a bit of time paging through the report in search of that information. He can't find it and finally agrees with Rodriguez's suggestion that it was Det. Phil Stoddard, the lead investigator in the case. Rodriguez points out that in the first scans, Dustin was using a man of 6 feet, 3 inches to establish the driver's sight line. Rodriguez then asks him whether he changed the sight line in the second scans to reflect that Ross Harris is an inch shorter, 6-2. Dustin says he used his own height. Rodriguez gets Dustin to acknowledge that the car seat was in a different positions in the first

Rodriguez asks Dustin some technical questions about the accuracy of the laser scanning process. Then, the lawyer asks about the first scans of the SUV and who positioned Cooper's car seat in the vehicle for purposes of the scans (it had been removed). This was more than two years ago, and Dustin isn't quite sure.

Carlos Rodriguez begins his cross-examination of prosecution witness David Dustin, an expert in 3D laser imaging. Led through direct examination by prosecutor Jesse Evans, Dustin has been demonstrating computer-generated images of Ross Harris's Hyundai Tucson.

The jury is brought back in and the trial is back in session. Evans says he misspoke about whether the defense had seen the SUV scans and wanted to apologize to defense counsel in front of the jury. He acknowledges that they haven't seen the scans in question but says they are nearly identical to the first such scans, which the defense has seen.

Judge Staley Clark listens to Rodriguez's arguments and to Evans's response and then overrules the defense objection. The images will be shown to the jury and the defense won't get to see them first. (Again, the prosecution argues that the defense has already seen the images.) Then the judge calls the midmorning break.

Rodriguez objects to the demonstration and asks that the jury be removed so the defense can get a look at what the next 3D scans will show. Evans argues that the defense has already seen the images, but Judge Staley Clark orders the jury removed so the parties can argue the issue out of their presence.

Evans shows photographs of the car as it actually appeared at the crime scene and compares them with the scanned image on the big screen, asserting that the scanned image is accurate down to rather minute details.

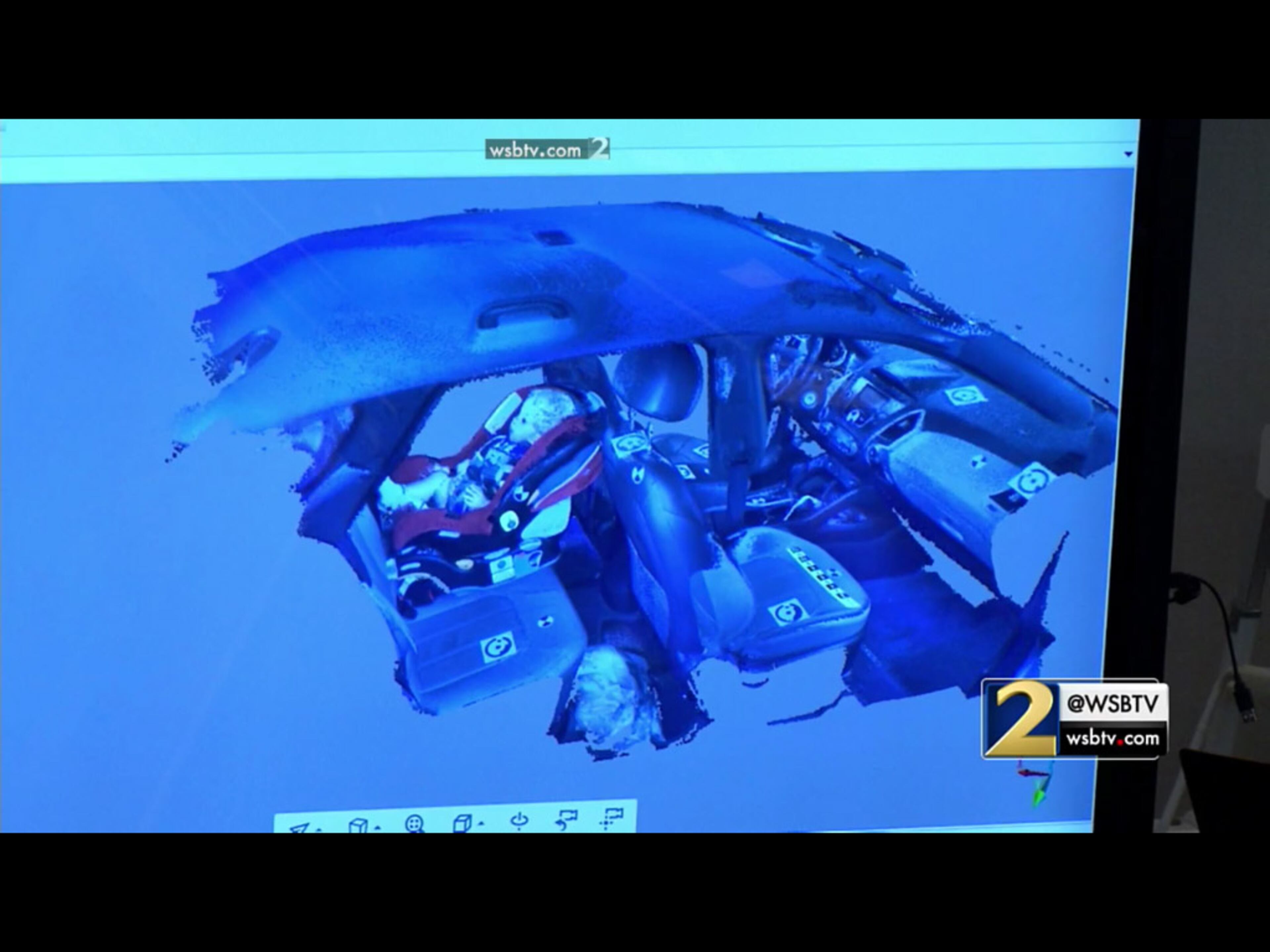

The image of the vehicle now zooms into the back seat where Cooper's car seat was strapped in. The doll depicting Cooper is lifelike and the view of it is disturbing.

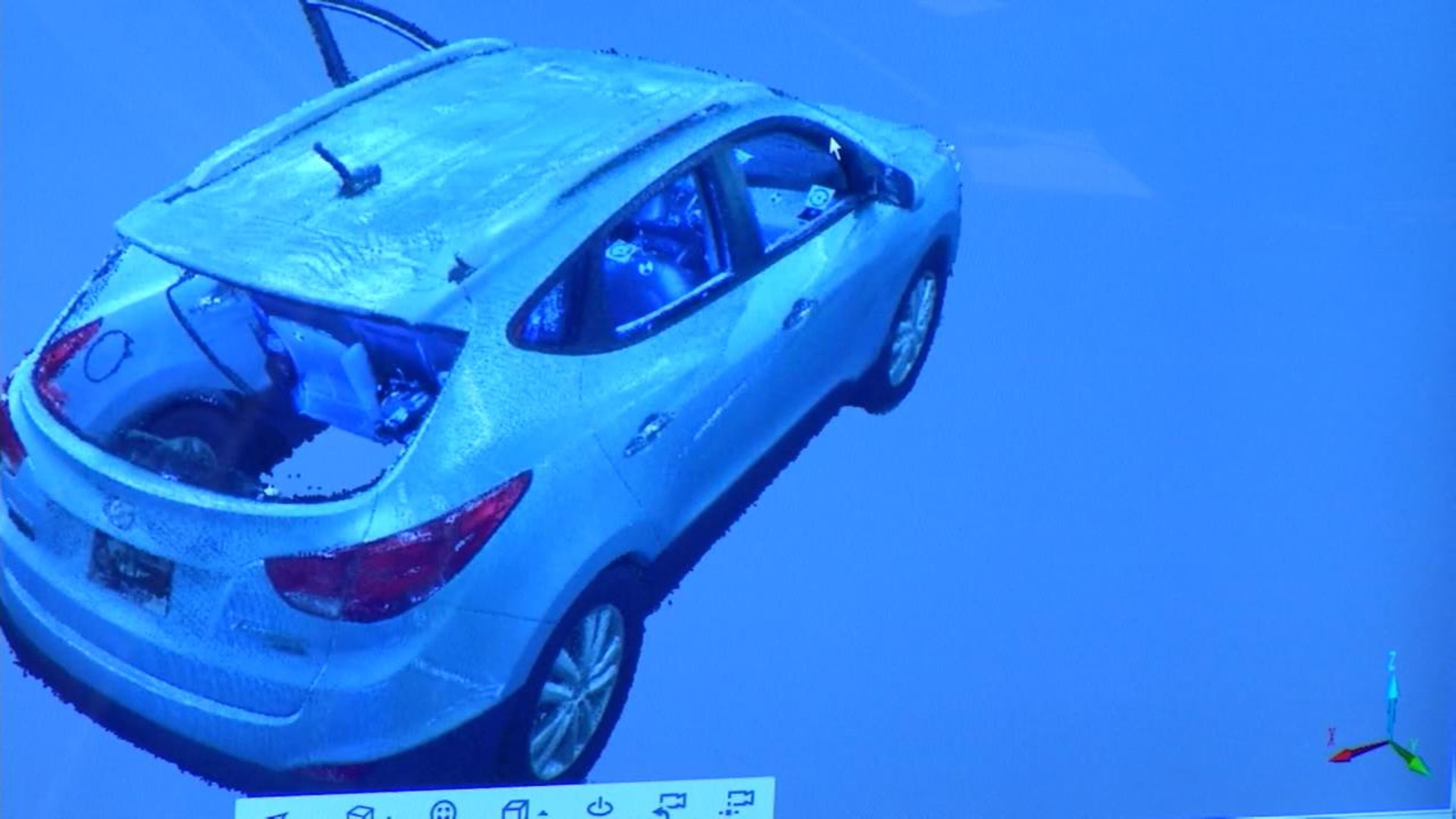

Dustin is now loading a new image onto the big screen showing an exterior view of the SUV with the front driver's-side door open. He explains that the scanner sometimes has trouble "reading" glass because of glare and other factors, and there are opaque patches on the windows of the car. As a result, he tells Evans, he "removed" the window glass from the vehicle. The interior of the car is now clearly visible. He then zooms the view in to the open front door, in which the interior is visible in detail.

Evans shows a hard-copy image of the interior of the SUV, showing the position of Cooper's car seat and also containing a doll representing Cooper.

Defense attorney Rodriguez objects to the way Evans is leading the witness through the image, arguing that Evans is testifying and the witness is simply confirming what he says. Evans says he'll rephrase the question. Dustin testifies that he and a Cobb detective traveled to Glynn County about two weeks ago for purposes of performing a 3D laser scan of the Harris SUV.

Dustin displays the Akers Mills Square area and tells Evans (at left in the image above) he was able to position Harris's SUV there because investigators had marked the vehicle's tire positions before removing the vehicle from the parking lot. In this rendering of the car, the vehicle does not have a roof. Looking from above, the viewer can see inside the car.

Evans asks whether this sort of 3D photo-rendering can be done outdoors as well as inside. Dustin says yes. Dustin acknowledges that the Cobb police asked him to scan the Akers Mill Square shopping center to create a similar 3D mapping of the place where Harris stopped and pulled Cooper's body out of his SUV. It takes a moment to load this onto the screen.

The defendant changes chairs at the defense table so he has a better view of the flat screen the prosecution is using. The first view is a 3D laser scan of the courtroom, to demonstrate the accuracy of the process, Evans says. The rendering of the courtroom is an extraordinarily clear image in which Dustin can change the view to practically any vantage point, as if the viewer were moving around the courtroom, ducking down, looking up, etc.

Evans submits the videos as evidence. Rodriguez rises to ask the witness questions about the videos before they're shown. He asks Dustin how he determined the arrangement of various objects, including people, in Ross Harris's Hyundai Tucson SUV for the purposes of creating a computer model of the vehicle. Dustin says police investigators gave him that information.

Prosecutor Jesse Evans is handling the direct examination of Dustin. Evans introduces the 3D animation video that Dustin's firm developed. Defense attorney Carlos Rodriguez objects, saying the video is a demonstrative aid and not evidence and shouldn't be introduced as evidence. Judge Mary Staley Clark overrules him.

Court reconvenes. David Dustin, an expert in 3D laser scanning and image mapping returns to the stand to continue his testimony from yesterday.