For many years, Grady Memorial Hospital loaded up a bus with mentally ill patients at 4 p.m. every day and shipped them off to state mental hospitals.

Those days are over, but the flow of people coming to Grady for mental health treatment hasn’t slowed. Across the state, more than 280,000 adults battle severe mental illness every day. Many of them are uninsured with little or no access to treatment that could help them lead healthy, productive lives.

The toll on these individuals and their families is devastating. But the burden these uninsured put on Georgia’s hospitals, charity clinics, jails, courts and other services is ultimately born by every Georgia taxpayer.

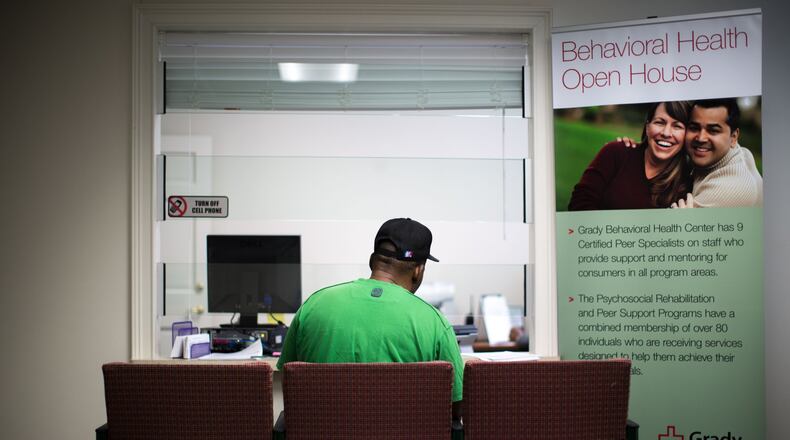

“There’s not enough routine services out there in Fulton County or anywhere,” said Michael Claeys, head of Grady’s behavioral health services. “These are the people nobody else is going to serve.”

Statewide, Georgia hospitals since 2010 have spent roughly $158 million caring for uninsured patients with mental illness — money they won’t get back. They saw more than 51,000 of these patients last year alone — a 35 percent increase in the past five years, Georgia Hospital Association data shows.

Those losses, experts say, are passed along to patients who can pay in the form of higher hospital bills and health insurance premiums.

People without insurance put off treatment again and again, and their mental health deteriorates, said Earl Rogers, president of the Georgia Hospital Association. A typical outcome, Rogers said: the patient ultimately must be institutionalized for an illness that could have been treated effectively much earlier.

“It costs society dearly in the long run,” he said.

ER will have a psychiatric section

The closing of two state mental hospitals in Rome and Thomasville, as well as the end of most adult mental health services at Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, has placed additional stress on hospital emergency departments in recent years.

The shutdowns stem from a five-year settlement agreement between Georgia and the U.S. Justice Department after revelations of the deaths and abuse of dozens of patients in state-run mental institutions. Under the settlement, the state has invested roughly $1.14 billion in community-based adult mental health services, such as housing and intensive case management.

The need is far greater than the 9,000 individuals targeted by the settlement, said Claeys with Grady. Fulton and DeKalb counties alone have an estimated 100,000 people who suffer from severe and persistent mental illness, he said.

The funding Grady gets from the Justice Department settlement, about $2.5 million a year, is ultimately a drop in the bucket compared with the need, Claeys said. It funds services for about 600 people a year. But the hospital gets at least 800 patients a month just coming through the ER — four times as many people as just three years ago. Its 24-bed psychiatric ward is nearly always full.

The safety net hospital loses up to $10 million a year caring for uninsured mental health patients. In 2014, it established a new outpatient program for the 300 or so patients it discharges from its psychiatric ward each month, so they can get next-day follow-up care instead of having to wait six to eight weeks for an appointment. Grady also created a team of counselors and social workers who staff the ER 24 hours a day to work with mental health patients, and it’s in the process of adding five psychiatrists.

In the coming months, the hospital also plans to open a new ER that will have a section specifically equipped to treat mental health patients.

At Atlanta Medical Center, the hospital recently rolled out a program in which a psychiatrist is on call 24 hours a day for ER patients. A psychiatric evaluation team is also available to assess individuals in the ER and on patient floors and help physicians determine the best course of treatment.

As for Grady, instead of sending a busload of people to state mental hospitals every day, it now refers about 15 to 20 patients a month, a number Claeys expects to continue to decrease.

“We’ve done quite well with the resources that we have,” he said. “But the population is growing, and the number of uninsured is growing.”

‘Strike when the fire’s hot’

Georgia’s network of state-funded behavioral health centers, known as community service boards, is also struggling to manage the caseload.

View Point Health, which serves Gwinnett, Rockdale and Newton counties, treated nearly 12,000 people in fiscal 2014. About 55 percent were uninsured.

In 2012, View Point was part of a larger effort by the state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities to get people same-day care when they walk through the doors.

Often by the time people make it to a treatment center, they’ve struggled on their own, said View Point CEO Jennifer Hibbard. Under the new format, there’s no need to make an appointment, Hibbard said.

“They can walk in today, and we’re going to see them,” she said. “We need to strike when the fire’s hot.”

View Point is also seeking out other sources of funding. For example, the agency is using a nearly $250,000 grant through Gwinnett County to expand its crisis stabilization unit from 16 to 23 beds. Demand for the unit, designed to keep individuals in crisis out of state institutions, is so high that View Point can only admit about 27 percent of the people referred there, Hibbard said.

‘It’s a lot worse than that’

Millions of uninsured Americans who suffer from psychiatric disorders are also a persistent drain on the country’s justice system.

Some police officers and sheriffs’ deputies end up essentially having to babysit patients in hospital ERs for hours instead of going back on the street. Jails become de facto mental institutions.

Nationwide, one in five inmates at state prisons and local jails has had “a recent history” of a mental health condition, according to the Justice Department.

In Georgia, the closing of state mental hospitals has put additional pressure especially on sheriffs’ offices in rural areas.

Deputies spend hundreds of hours and drive thousands of miles transporting mental health patients to hospitals. It often falls to law enforcement to provide transportation when a court orders treatment or a person is involuntarily committed to an institution. In 2010, a survey of sheriffs’ offices showed deputies transported more than 20,000 people with mental illness, spending three to nine hours on average doing so instead of being available to respond to calls for help.

The cost: at least $1.7 million. That number, however, is likely higher since some counties didn’t respond to the survey or don’t keep those statistics.

Local taxpayers cover the entire cost, said Terry Norris, executive director of the Georgia Sheriffs’ Association, which conducted the survey.

“I think it’s a lot worse than that,” Norris said. “It is the No. 1 problem that we face throughout the state.”

So far this year, officers have already traveled nearly 2 million miles and spent more than 12,000 hours, transporting mental health patients. (That represents just 73 of 159 counties the sheriffs’ association has gathered data from so far.)

The community-based services established by the state under the Justice Department agreement are successful in keeping people out of crisis — and from becoming a burden on law enforcement — in some areas but aren’t working well in many places, Norris said.

“They wanted to place people in community settings, which is not a bad thing by any stretch of the imagination,” he said. But statewide, “the overall network of accessible resources just doesn’t seem to exist right now.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured