Inmates transcribe textbooks into braille, saving Georgia money

Deep inside Central State Prison, more than a dozen men spend hours each day hunched over a computer keyboard, transcribing math, literature and political science textbooks into braille.

The murderers, sex offenders and other criminals have set up their respective work stations with photographs, plants and books, just like any other office.

“When I come through that door each morning, I don’t feel like I’m locked up,” said Jay Dailey, who was sentenced to 60 years in prison in 2008 for wounding Fulton County police Cpl. Paul Phillips and assaulting a female motorist.

RELATED: After five inmates die, Fulton jail dumps health provider

ALSO: Civils rights groups say Atlanta court violates poor defendants’ rights

Dailey, 52, is focused on transcribing the stage directions and illustrations for the play “A Christmas Carol” into raised dots that can be read by a blind student.

“Since I’ve been here … I can see an opportunity down the road,” said Dailey, who is tentatively scheduled to be paroled in February 2026. “Unless I truly screw up in prison, I’m going home.”

He said the braille skills he has learned will enable him to leave prison “a changed man” rather than an angry one.

While inmates elsewhere in the prison spend their days in the bunks, gathered around televisions or sitting around talking with other prisoners, these men type on keyboards, proof the braille dots that blind students will read, or press the pages that will be bound into books for the Georgia Department of Education and the Georgia Academy for the Blind in Macon.

“We try to make it as much like a professional job as we can,” said Angie Scott, who oversees the program.

More than half the inmates in the program are serving life sentences or are sex offenders.

Scott said inmates must have at least three years remaining on their sentences to enter the program because it takes at least a year to be certified in braille by the Library of Congress and a few years more to become proficient in the language.

They also must have above-average scores on reading and math tests, a high school diploma or a General Educational Development (GED) diploma, and no disciplinary history.

And, Scott said, “they have to be very motivated.”

They transcribe about 63 books a year.

Georgia agencies do not pay for the transcriptions but provide materials the inmates use. Other states are charged, however.

MORE: Georgia prison scandal wraps up as last guard is sentenced

IN DEPTH: Drugs and booze abound at Atlanta federal prison camp

“Braille is so tremendously expensive,” said Cindy Gibson, superintendent of the Georgia Academy for the Blind in Macon. The commercial cost of transcribing ranges from $4 to $6 per braille page, she said, and one printed page requires many, many braille pages.

Carson Cochran, director of the Georgia Instructional Material Center for the Department of Education, said one algebra book, for example, would cost $60,000 if the state had to use a private vendor. He said the cost per book depends on how complex it is.

Scott said there are about 40 such braille transcription programs in prisons nationwide. The program in Georgia started in 2003 at a prison in Baldwin County and moved to Central State Prison in 2011.

The Georgia Department of Corrections boasts that none of the inmates who were in the program and later released have returned to prison. Corrections officials say they have “22 success stories” of former inmates who have careers or have their own braille transcription businesses.

Studies show that inmates who are educated or have job skills when they are released are less likely to resume a life of crime.

“Some of us come out good, ready to contribute to society,” said Ladji Ruffin, who learned braille in prison and now has his own business. “Not all of us come out with criminal behavior, (or) want to re-offend.”

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER: Know what’s really going on with crime and public safety in your metro Atlanta community. Get the latest breaking crime news, trial coverage, trends and unsolved cases. Sign up for our AJC newsletter delivered weekly to your inbox

Ruffin, now 43, was released from prison in August 2016 after serving 23 years for murdering his mother.

The year before he was paroled, Ruffin was assigned to a halfway house. During the day, he did work details at the Governor’s Mansion. And at night, he transcribed books into braille for Georgia Tech and the Department of Education, for which he was paid.

“I came out (of prison) with a lot of money (saved),” Ruffin said. “When I came out, wasn’t nobody waiting for me.”

As a free man, Ruffin won a contract to transcribe books into braille with the help of another former inmate and alumnus of the braille program, who by then worked at Georgia Tech. Ruffin said other contracts include a company in Canada and school systems in Georgia, Tennessee and Texas.

His business is Authentic Braille Masters. “When people go looking for companies for braille, it’s in alphabetical order. People don’t like scrolling down,” Ruffin said. “That’s why I picked ‘Authentic.’”

He has two employees, one of them a former inmate.

“In the braille world they don’t care” if transcribers were felons, Ruffin said. “I just do the work. … I’m not stepping into nobody’s school. I’m not stepping into nobody’s office.”

One recent morning, Elmer Hamilton, who’s serving three consecutive life sentences for a 1992 murder he committed when he was 18, was proofing a braille American government and civics textbook. It’s “dense” reading, the 44-year-old Hamilton said.

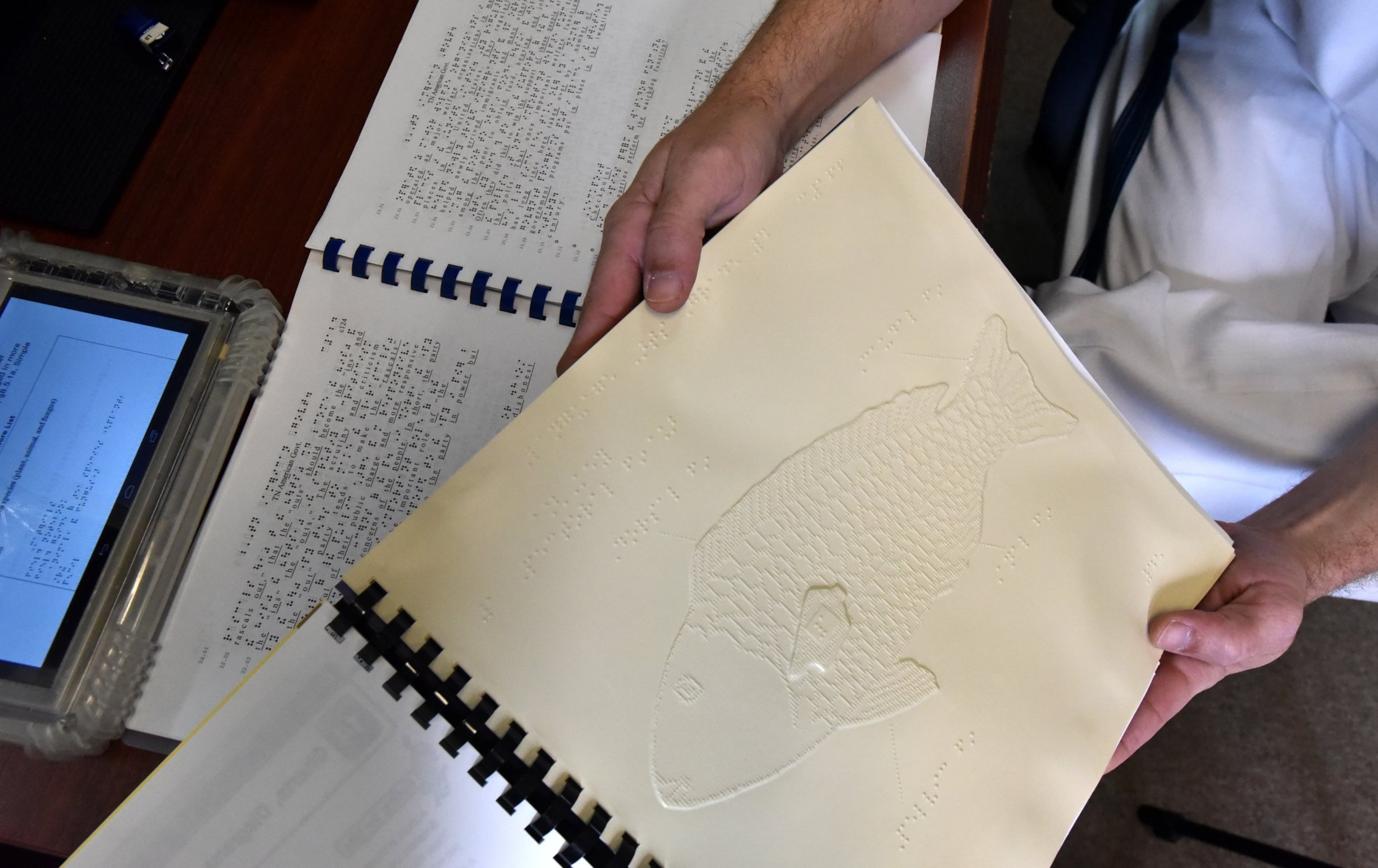

He prefers transcribing math books. And he enjoys the challenge of turning images into a series of dots.

Recently, those images were of a fish and an erupting volcano. He asked a visitor to feel the scales and fins and lava flow and ash clouds he’d created.

“I’ve held out hope (of getting out) for 25 years,” Hamilton said, adding that being in the braille program will help him when the State Board of Pardons and Paroles looks at his file.

“It’s the only program I’ve taken in prison that’s given me direction,” he said.