DeKalb Sheriff Jeffrey Mann says the protesters who claim DeKalb County’s jail is unsafe and unsanitary have no credibility.

To be taken seriously, he said, they need to file formal complaints and supply evidence instead of taking to social media or participating in violent demonstrations.

“Just out there creating a disruption rather than being productive and rather than calling, emailing or going on the website: it’s not fruitful,” Mann said.

Recent viral posts on Twitter and Instagram have highlighted more than just the black mold inside the jail, which has been an ongoing issue for Mann and one he says already has a solution in the works. Malaya Tucker posted pictures of her son and other inmates posting signs, including one that said in all capital letters, "Please help, we dying, need food."

Tucker said her son has been beaten by guards and punished for speaking out about poor treatment by corrections officers and lack of access to health care.

“It does not make sense to me that this jail is operating the way it’s been operating,” she said.

But Mann said he is skeptical of her story and others that have been amplified by the Atlanta chapter of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, an inmate-rights group.

Atlanta Anarchist Black Cross and the support group, Mothers With Sons In Prison, have also spoken out about conditions at the jail.

Mann criticized some of their tactics, which included a protest earlier this month that turned violent and ended with an officer injured and the arrest of several protesters.

“I want to express my disappointment that groups like the Atlanta Anarchist Black Cross would come into our jail lobby, throw firecrackers and smoke bombs, assault one of the DeKalb County police officers with a stick and create a disruption in our workplace instead of utilizing the many methods they have to bring concerns to our attention,” he said.

As far as the mold, Mann has long acknowledged the aging, 1 million square-foot building has issues. But a massive remediation program is scheduled to start at the end of the month. It will require a temporary kitchen to be built to accommodate approximately 1,700 inmates and hundreds of employees for three months while the black mold in the old kitchen is removed.

Although the county commission put $864,835 in the 2019 budget for maintenance at the jail, it was far short of the $9.5 million that Mann requested. He is now working with CEO Michael Thurmond’s staff to consider additional funding when the county commission approves budget increases this summer.

Last year, Mann received $1.5 million in emergency funding to address mold issues in the dormitories and other common areas. That work was completed, he said.

He dismisses complaints that inmates are being denied access to medication that keeps them alive, beaten by guards, assigned to solitary confinement, and stripped of privileges when they criticize jail conditions. He said those grievances have not been made appropriately or they lack specific details.

For example, he said people have called various departments at the Sheriff’s Office, Mann said, but when county employees try to transfer them to the Office of Professional Standards to begin a formal complaint they are met with a dial tone.

“It’s obvious they only called to vent,” he said.

County Commissioner Mereda Davis Johnson, who chairs a committee that has oversight of the Sheriff’s Office, reached out to Mann after the social media posts caught her attention. She agreed that it was hard to give them credibility without formal complaints.

“You have to take formal steps in lodging complaints so they can be individually investigated,” Johnson said.

Meg Dudukovich, who serves as the spokeswoman for Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, said it is the Sheriff’s Office that has closed the lines of communication.

She said many people who called to raise their concerns were put on hold, transferred endlessly or hung up on.

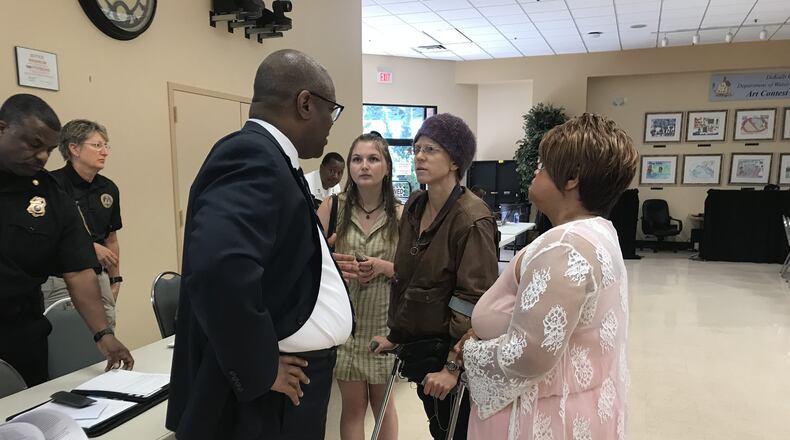

Dudukovich and a few others spoke during public comment at the county commission meeting on April 23. Joining her was Adele MacLean, who rattled off a series of concerns discovered after engaging with people coming in and out of the jail for visitations.

“I spoke to a person in the jail two weeks ago who had just witnessed a diabetic man get ill after going without insulin,” she told commissioners.

Zach Williams, the county’s chief operating officer, met with them briefly during the meeting and gathered their contact information. Williams said he shared their concerns with Mann, who promised to look into it.

That hasn’t seemed to lead anywhere, Dudukovich said.

“Despite our attempts to contact jail officials,” she said, “it seems everyone has tried to avoid taking responsibility and/or answering questions.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured