Charge card users in DeKalb County’s government have hit their credit limit.

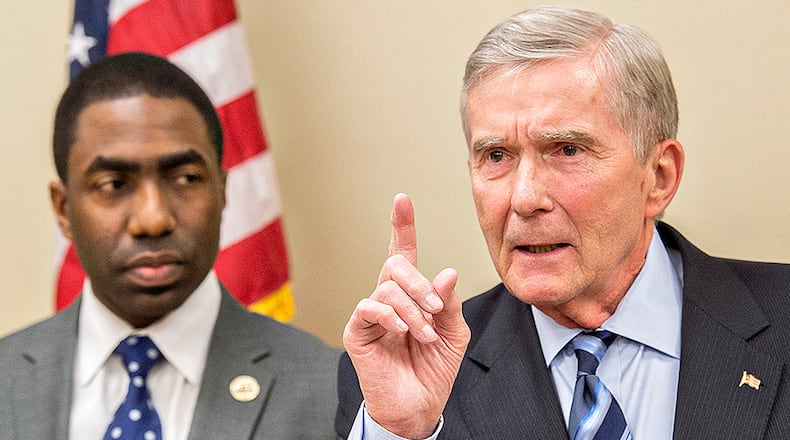

Interim DeKalb County CEO Lee May announced Monday that he’s indefinitely suspending the use of taxpayer-funded purchasing cards, which at times have been handed over to pay for personal items like plane flights, cellphone charges and ski resort bookings.

May’s decision is based on recommendations from special investigators, who found examples of suspicious expenses that didn’t benefit the county.

The investigators, led by former state Attorney General Mike Bowers, were hired by May three months ago to uncover fraud and corruption in county government. They told May they have come across instances of government employees using the cards to buy unauthorized items and splitting purchases to circumvent the county’s $1,000 per transaction limit. Details of their preliminary findings have not been released.

“Progress is being made every day but major challenges remain in our commitment to root out any abuse, corruption or malfeasance. This is the primary reason why we hired special investigators,” May said in a statement. “I am serious about restoring the public’s confidence.”

The charge card ban applies to county commissioners, their staffs and most of the nearly 300 DeKalb employees who have been issued P-cards. The cards may still be used in some circumstances, such as for emergencies, motor vehicle repairs and court expenses.

Several DeKalb government officials have been accused of abusing the cards, including former Commissioner Elaine Boyer, who is serving a 14-month sentence in federal prison after she pleaded guilty last fall to bilking taxpayers of more than $100,000.

Some residents said the purchasing cards should have been eliminated a long time ago.

“They were just giving everybody a blank check with no accountability,” said Tom Owens, who filed an ethics complaint against Boyer. “It’s about time.”

Viola Davis, who watches the county for waste of taxpayer money, said DeKalb needs a full forensic audit to ensure spending is appropriate.

“Purchasing cards are too easy for irresponsible elected officials to abuse,” Davis said. “With the limited amount of funding we have, we have to make sure every dime counts.”

Besides Boyer, others have also faced allegations that they used their purchasing cards for personal items instead of legitimate government business.

Her former chief of staff, Bob Lundsten, has pleaded not guilty to charges that he used his taxpayer-backed purchasing card to buy about $200 to $300 worth of unauthorized items. Several commissioners also have faced ethics complaints, alleging they misspent funds with their cards.

An audit of the county’s purchasing-card spending found lax oversight of the program and receipts missing for some expenses. The audit found that the DeKalb Board of Commissioners and its staff have spent $257,170 on P-cards since 2006. Receipts were submitted for only 57 percent of those transactions.

Commissioner Sharon Barnes Sutton said too much emphasis has been placed on minor charge card purchases.

“We’re focusing on the sensational part, the P-card purchases,” she said. “I want to get to the meat and potatoes and see what’s going on” in other areas of government, like the Department of Watershed Management.

Commissioner Kathie Gannon said the cards should be eliminated permanently if investigators have found more problems.

“Get rid of them. It’s one less problem,” Gannon said. “Why did it take so long?

The Georgia General Assembly passed a bill this year that made it easier to bring felony charges against elected officials who misuse charge cards. The legislation initially would have barred purchasing cards, but some governments successfully argued that the cards served a legitimate purpose, especially when officials in local governments are responsible for purchasing.

“Just to give somebody a credit card and entrust they’re going to be used properly without some checking is not a good idea,” said Dan Wright, who worked with a group called Blueprint DeKalb to push lawmakers to enact stricter purchasing rules. “I’m all for getting to the bottom of the P-card problems. I just want them to do it and get it done.”

The investigation led by Bowers had cost the county $62,864 through March at a rate of $400 an hour, according to an invoice obtained by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution through an open records request.

When the investigation is completed, a public report of its findings will be released.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured