Coming tomorrow: District Attorney Paul Howard apologizes about lack of action against crime-ridden properties.

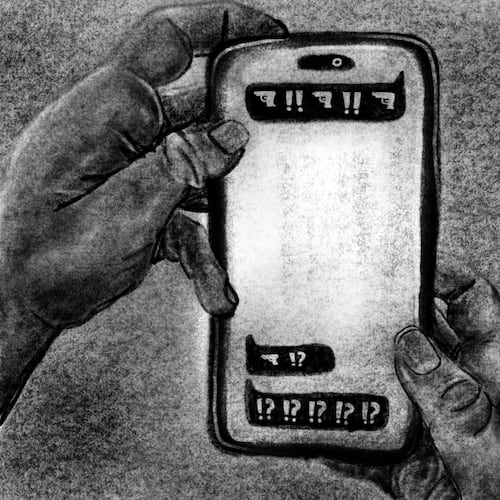

It’s no secret that Jett Street Apartments were trouble. Plenty of people tried to do something about it. All they got was more reasons to be angry.

Investigators busted drug sales operations there at least 11 times in four years. Elected officials fielded complaints about trash, junk and rats. Atlanta police were called there for fights, drugs and other crimes some 500 times since 2009.

Still, illicit businesses thrived for a decade in and around the two battered buildings just west of the Falcon’s stadium downtown, according to law enforcement records and neighbors. Dealers sold drugs in broad daylight, and one was shot dead there. Stolen cars stripped of parts turned up in its parking lot, and a bootleg liquor store was run from one apartment.

The history of these 18 apartments in the English Avenue neighborhood shows how difficult it is to clean up properties that pose even the most obvious threats to safety.

Police, city and county officials have limited powers to pressure property owners to keep criminals away and fix up blighted buildings. Authorities missed what chances they did have for lack of money, attention or commitment. This broken system leaves crime-ridden houses and apartments to cycle in and out of the legal system, remaining just as dangerous as ever.

City officials say they are now devoting money and attention to reforms, but whether those will work remains an open question. Conditions at the Jett Street Apartments only started to change when a neighborhood association resorted to extreme measures: joining forces with federal prosecutors to try to seize the buildings from its owner by filing a forfeiture lawsuit.

Yet that process is so difficult and time consuming that it generally is no real solution to the city’s blight problem, said Sally Quillian Yates, the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Georgia. There are dozens of English Avenue properties just like it, and police records show hundreds more across the city with repeat drug activity.

“This is not the most efficient way to be addressing these properties,” Yates said.

She declined to comment on the Jett Street Apartments because the seizure case is ongoing, but she agreed to talk about her agency’s initiative to clean up English Avenue properties that are overrun with crime.

The buildings' owner, through an attorney, declined comment, also citing the court case. But in a legal filing, Woodstock businessman Joseph Cardoni, who owns the apartments through his company Investment Properties of North Georgia, described his property and law-abiding residents as victims of the "inability or unwillingness" of police and federal prosecutors to address problems in the neighborhood.

The real issues, his filing says, are nearby dilapidated and abandoned properties. “These properties apparently are allowed to fester without repercussion or consequence,” the filing alleges. “These properties attract and provide cover for the individuals who allegedly perpetrate crime at and around the defendant properties.”

A promising target

In theory, Jett Street Apartments was a promising target for a cleanup.

While owners of problem properties often hide their identities behind shadowy corporations, Cardoni is easy to find. His name is on state documents, and he even called back police when they contacted him.

In reality, however, some remedies available to the city and county were inadequate, or ran the risk of creating more problems than they could solve. At least one was overlooked.

The city could have turned off water service to get Cardoni’s attention because his business owes $45,000 in overdue bills on these buildings alone. But then tenants — not the owner — would suffer the consequences.

It also could have sought to demolish the property. Reports to city code enforcement complained of overflowing dumpsters, rats, junk and dilapidated conditions. When one case was resolved, others would follow.

But demolitions cost taxpayers an average of $20,000 each, and hundreds of properties are ahead in line.

And while the city could levy fines, they are so low — the highest is $1,000 — that it can be cheaper for landlords to pay up than make repairs.

“We have a revolving door,” said City Councilman Ivory Young, whose district includes English Avenue. “We often see properties in the courts year after year after year, and no evidence of compliance.”

Two county agencies also could have tried to take away Cardoni’s properties.

Fulton Tax Commissioner Arthur Ferdinand could have taken action because Cardoni’s business owes more than $33,000 in unpaid tax liens on the apartments, according to property records. By law, Ferdinand is allowed to file suit to foreclose on tax-delinquent properties and may sell them on the courthouse steps to recover the money. As an alternative, he could have sold the debt to an investor who could seek to have the property auctioned off if the owner fails to pay up.

But investors avoid buying liens in distressed neighborhoods such as English Avenue, Ferdinand and other experts said. And Ferdinand said he wouldn’t go to the expense of asking a judge to foreclose on a property unless he knew there would be an interested bidder.

When a sale fails to go through, taxpayers foot the $5,000 in legal bills, and the real estate returns to the delinquent owner, tax experts said.

The Fulton County District Attorney’s Office also could have sought to seize the Jett Street Apartments. Atlanta police sent eight “cease and desist” letters to owners of the Jett Street Apartments in 10 years, warning that the district attorney could seize it for repeated drug activity.

But while police routinely refer problem properties to the Fulton County district attorney’s office for forfeiture, prosecutors have not tried to seize one since 2004. Fulton District Attorney Paul Howard told the AJC he was unaware police had been making these requests.

Even if such seizures are made, they can be expensive and time consuming. A new owner would have to reckon with water bills, mortgages and other debts that can easily total more than such buildings are worth. Putting up fencing, boarding up windows and keeping the yard clean only adds to the cost.

The Fulton County/City of Atlanta Land Bank Authority is set up to do some of this work, but it can handle only a small portion of the area’s thousands of blighted properties. It operates with three employees and a budget of $280,000.

Without a real threat of forfeiture, owners have little incentive to boost security.

Vicious cycle

The English Avenue Neighborhood Association tried to address problems itself. In a sign of solidarity and defiance, the group stood on street corners controlled by drug dealers. They also asked that police be stationed outside the Jett Street Apartments. Officers came for a while, but the effort was not sustained, said Demarcus Peters, the association’s president.

“We’ve done our fair share,” said Peters, “and in many cases, moved in on the role of what the Atlanta police department should be doing. And we’ve put our lives at risk as well.”

With no one but neighborhood groups seeking a permanent solution, criminals made themselves comfortable at the Jett Street Apartments.

Dealers and prostitutes tried to sell to motorists who turned into the driveway. Crowds of addicts acted as lookouts. Police found scales and baggies to measure and package drugs stashed inside. Year after year, they spotted the same drug dealers there.

Addicts walked surrounding streets as if they were in a daze. Doors stood open at all hours, and loiterers yelled and cursed.

“By the time they (authorities) did something, it was under drug dealer control,” said the Rev. Darrion Fletcher, of Walking Through the Vine ministries.

Neighbor Larry Sloan watched the chaos from his back porch.

An elderly manager would try to convince tenants to pay rent, but they brushed him off. He was in no physical condition to confront drug dealers.

“It was just like talking to a tree. And he was an old tree,” Sloan said. “He had one eye, as a matter of fact."

When Cardoni showed up, the dealers would scatter. When he left, they returned, Sloan said. Three or four months later, the owner would come back, and they’d begin again.

But while Cardoni filed to evict tenants for failure to pay rent, he did not seek to evict them for drug use or other crimes, according to a federal filing.

And there’s little evidence the owner tried to enlist police to keep dealers away. Before this year, the last time officers responded to a trespassing call at the apartments was in 2010, records show, and the head of the agency’s patrol operation says Cardoni never asked his office for help.

“With this particular property, it’s obvious the owner doesn’t care about the community around him,” said Deputy Chief C.J. Davis.

Davis and Deputy Chief Joe Spillane, who oversees the agency’s patrol officers, said police can arrest unwanted visitors for criminal trespassing only if someone requests it.

“These are private properties, and the responsibility for security on private property is with the owner of the property,” Spillane said.

Without the help of a property owner, police are left responding to 9-1-1 calls, policing crime from public right-of-ways, conducting narcotics busts and directed patrols, and executing search warrants. Records show they used all of these tactics repeatedly at Jett Street.

Vacant and boarded up

If the U.S. Attorney’s Office had not filed suit, the Jett Street Apartments would still be run by criminals, neighbors said.

Peters and other English Avenue Neighborhood Association members pointed out the apartments to federal prosecutors nearly three years ago, during a tour of locations with the worst crime.

Yates was looking for strategies to prevent criminal activity in high-crime locations and decided to try to seize the property. Federal law allows courts to use the forfeiture process if an owner knows that drug crimes are taking place and does not take reasonable steps to stop it.

“Our goal here is not to take people’s properties,” Yates said. “Our goal here is to get the property owners to do what they should be doing to prevent the criminal activities going on.”

In late 2013, Yates' office filed suit, and city code enforcement followed with crackdowns.

This past June, code enforcement deemed the apartments unfit for human habitation.

Still, months later, drug dealers remained. Finally, the Rev. Fletcher coaxed them out over two weeks, he and Peters said.

Then, through Fletcher, who also works as a contractor, Cardoni hired workers to clean up the vacant buildings. By the end of October, much of the trash was gone and the windows were boarded up.

Neighbor Sloan wondered why it took a preacher to chase the dealers away.

“He’s done what I’ve seen nobody else do,” Sloan said. “I didn’t understand why police didn’t do that. It wasn’t nothing police couldn’t have handled.”

Meanwhile, the federal forfeiture case is dragging on.

And even now, addicts come there looking for a fix. The day before Halloween, Fletcher found a dead woman inside. Two heroin needles lay nearby on the floor, he said.

Neighbors still don’t trust Cardoni to keep the property safe. In early November, 60 corporate volunteers and members of the English Avenue Neighborhood Association hauled away piles of trash and painted flowers on its boarded-up windows.

The cost to Cardoni: Nothing. The labor and supplies were free.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured