One year ago Thursday, a mass shooting in a Florida school poured fresh fuel onto the gun-control debate, brought changes, and calls for changes, intended to make schools safer, and turned teens into activists.

The aftermath still echoes across Georgia and metro Atlanta. School districts have increased police staffs and expanded safety drills, and two have authorized teachers to carry guns. The Legislature has allocated millions, with the new governor urging more, for school safety. And for many of the students who banded together and demanded the country's attention, the political activism born last spring endures.

“I am optimistic that we can make change, this whole movement has been the biggest surge of youth activism since the Vietnam War and that’s a pretty big deal. I think something will come of this,” said Natalie Carlomagno, 16, a junior at Walton High School in Cobb County.

VIDEO: More on the Parkland anniversary

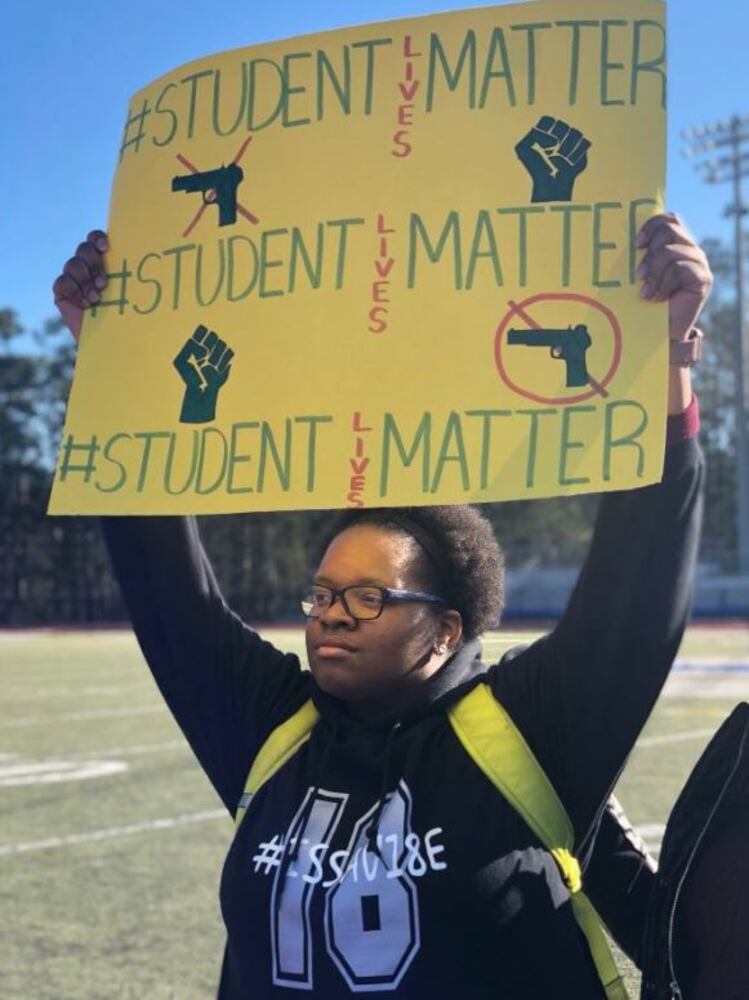

A month after a gunman shot and killed 17 people on Feb. 14, 2018, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., young organizers planned more than 3,100 school walkouts across the country, including dozens in metro Atlanta. Thousands of area students left classes for 17 minutes to call for more background checks for gun buyers, a semi-automatic assault rifle ban and other changes to reduce gun violence.

Metro students from middle school to college organized a march from The Center for Civil and Human Rights to Liberty Plaza where national, state and local advocates for gun control spoke about keeping schools safe.

Over the summer and until the November mid-term elections, some of the most dedicated local students pressed on. They held town hall meetings, a voter registration drive and made calls in support of gun-reform candidates.

“I think a lot of people my age who aren’t really sure if they’re Democrats or Republicans, they care a lot about gun violence still,” said Madeleine Deisen, 18, who helped organize the Walton High School student walkout as a senior and now attends George Washington University. “We sort of grew up with it around us, but Parkland definitely changed how I personally thought about it.”

Not everyone concerned about school safety believes restricting gun ownership is the solution.

“Disarming the victims isn’t going to make them safer,” said Jerry Henry, executive director of GeorgiaCarry.org. “Good people need to have some way to defend themselves. Criminals fear armed citizens more than they fear law enforcement,” he said. “They can watch police, but they never know who else may have a gun.”

He cited legislation passed in 2014 that allows school districts to decide if they want to allow teachers to carry guns as a step in the right direction for keeping students safe.

- MORE PHOTOS: Atlanta's March for Our Lives rally | National walkout | Victims remembered

Two Georgia school districts passed ordinances last school year allowing teachers to carry guns.

Daniel Brigman, superintendent of Laurens County schools near Macon, said gun-toting staffers would be trained by the sheriff’s department and their identities will be kept confidential. The program was set to go online in August. Fannin County, on the Tennessee border, also decided last school year to allow teachers to carry guns.

Deisen and other Cobb County students volunteered to campaign for Lucy McBath, the Democrat whose teenage son was shot and killed in 2012 and who won the race last year for Georgia's 6th Congressional District.

“I am fortunate to have so many young people volunteer on my campaign. I see qualities of (my son) Jordan in every one of them. We are raising an entire generation of children who know that we cannot afford to wait any longer for gun-safety measures,” said McBath in a written statement.

McBath is so close to the Parkland student activists that she planned to keep her new Washington office stocked with snacks for them.

The youth movement was sparked by a group of well-spoken teens who expertly used social media to call for gun-law changes. Organizers want this year to be about action of a different kind. There are no school walkouts, marches or large-scale demonstrations planned.

“We don’t want to just be known for marches and protests,” said Ethan Asher, state director of March For Our Lives Georgia. “That was great to get recognition and bring people into the cause, but now we are getting more organized and focused on the goal of gun control.”

While gun-control legislation was a main focus of the students’ demonstrations, responses in Georgia to Parkland so far have focused instead on the broader concern of safer schools.

“Parkland was a turning point on how we address safety in our schools,” said Forsyth County Schools spokeswoman Jennifer Caracciolo. “We created a joint safety task force with the sheriff’s office, conducted random safety audits of our schools/buildings … increased the bond funding up to $7 million for safety and started implanting capital improvements this fall.”

Increasing school police forces was a common theme: Gwinnett County added 15 officers — 10 at the elementary school level and five that offer support in the evenings — to bring its total to 89. DeKalb County added 10 school police officers and two K-9 officers. Henry County now has a school police officer at all middle and high schools.

Fulton County Schools, which already had police assigned to middle and high schools, hired 16 additional officers to patrol elementary schools. The district also committed to hiring 10 non-sworn employees to beef up security and monitor video surveillance systems. Fulton's safety plan includes creating an online mental health resource center that offers information and resources for students about depression, bullying and other issues.

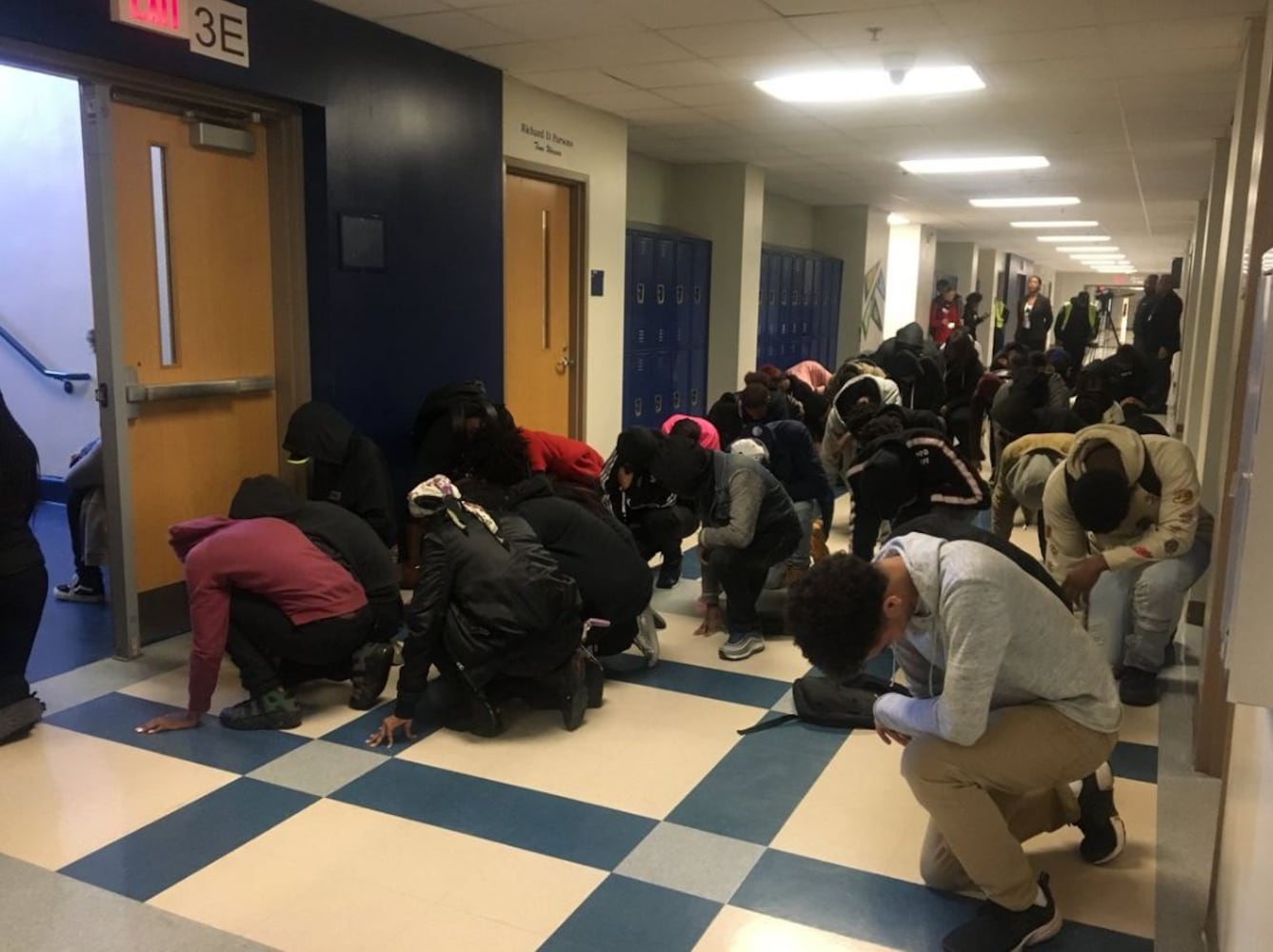

In Atlanta, efforts have focused on ramping up training for teachers, district employees and police officers, who now run through active-shooter scenarios using non-lethal bullets. Bus drivers and other school personnel are being taught to detect signs a student may be in mental health distress.

Clayton County is also focusing on training. “The incident in Parkland prompted us to review district safety processes to ensure our current plans are consistent with active-shooter best practices,” said Thomas Trawick, the district’s chief of safety and security. “Additionally, we created a process to assess, train and conduct drills to prepare our students and staff.”

The Cobb County school district did not respond to repeated requests for comment by email and phone.

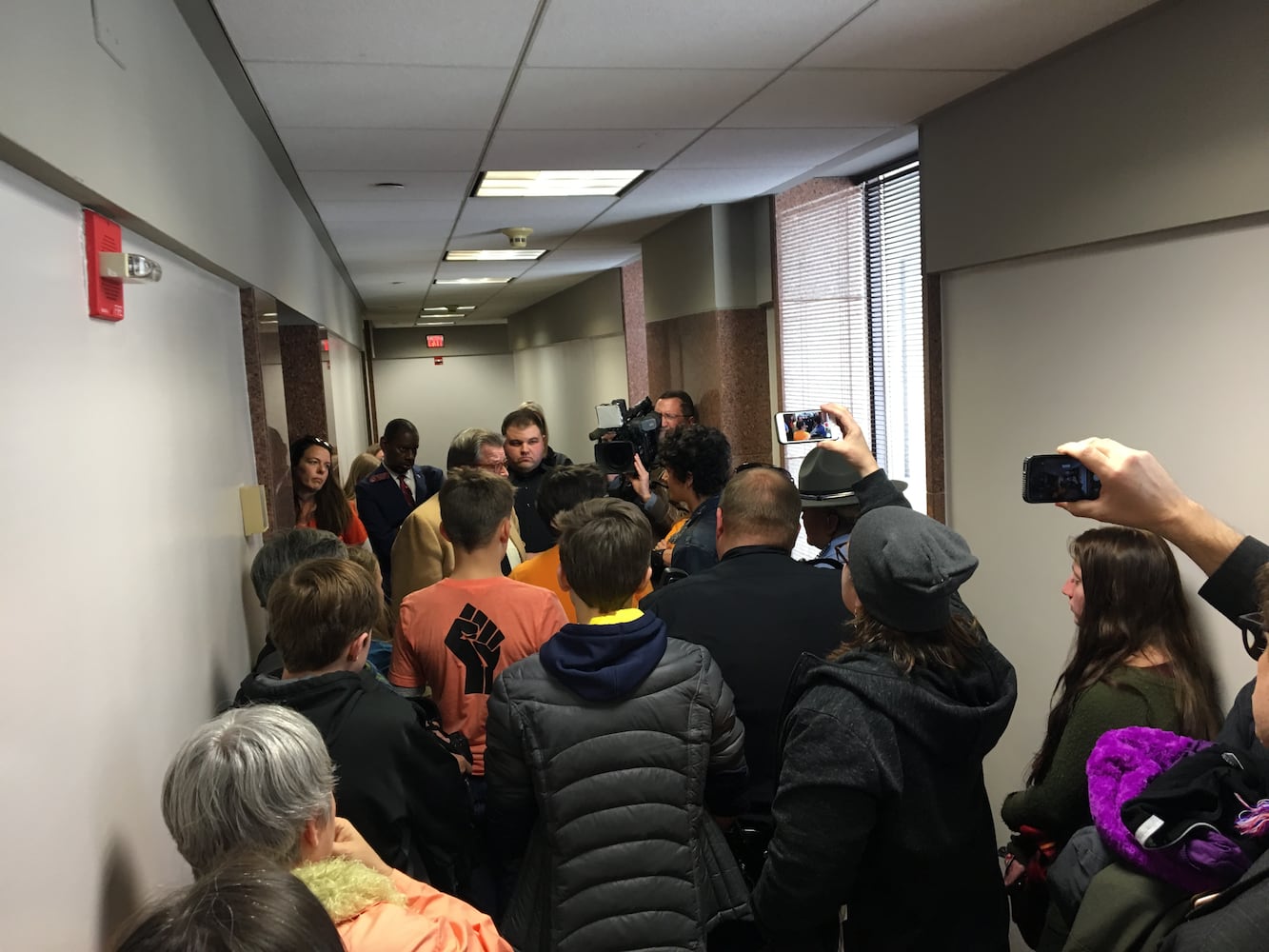

Nationally, the Federal Commission on School Safety headed by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos was formed to search out best practices and give recommendations. Georgia convened House and Senate school-safety study committees to do the same. Legislators allocated $16 million last year for the state's 180 public school districts, which hasn't been doled out yet. A proposal by Gov. Brian Kemp calls for $69 million.

A bill currently under scrutiny would put a mental health counselor in every one of the state's 2,200 public schools. At an average salary of $45,000 the cost would be close to $100 million — not including benefits. Another bill would use records from schools, law enforcement and state social service agencies to curate "student profiles," to identify those likely to make a violent attack.

Many young activists believe Parkland’s legacy will reach from high school hallways to voting booths, ushering in changes as their generation comes of age.

“The voice of the people is in those votes,” said Rhea Singi, 15, a sophomore at Cobb County’s Wheeler High School. “I think we realized this issue has taken lives for too long and too often and we can’t just sit still and wait for the adults to make change.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured