Gainesville parents Aaron and Jenny Moyer are among dozens of American families in the process of adopting Russian children. Thursday, they were anxiously waiting to see if Russian President Vladimir Putin will dash their dreams.

The Moyers, who have two biological sons and an adopted daughter, fell in love with a 4-year-old Russian boy who has Down syndrome when they traveled to meet him in October. They had hoped to finalize adoption of the boy, named Vitaliy, in the coming year, saving him from a life in an asylum or orphanage. Now that plan is in limbo as they wait to see if Putin signs legislation to block children once destined for American homes from leaving the country.

At a televised meeting Thursday, Putin said he intends to sign the bill. The Moyers say they are praying that he won’t.

“I just hope that we can bring our son home, and I hope other families can bring their children home,” said Aaron Moyer. “We know God called us to do this very specifically, so we trust in his sovereign hand. But we still long to have our child with us.”

UNICEF estimates that there are about 740,000 children not in parental custody in Russia, while only 18,000 Russians are now waiting to adopt. Russian officials say they want to encourage domestic adoptions.

But many fear orphaned children are being sacrificed to make a political point. The bill is seen as retaliation for an American law that calls for sanctions against Russian officials deemed to be human rights violators, including a prohibition on them entering the U.S.

Kremlin critics say that means Russian officials who own property in the West and send their children to Western schools would lose access to their assets and families.

Putin said U.S. authorities routinely let Americans suspected of violence toward Russian adoptees go unpunished — a clear reference to Dima Yakovlev, a Russian toddler for whom the adoption bill is named. The child was adopted by Americans and then died in 2008 after his father left him in a car in broiling heat for hours. The father was found not guilty of involuntary manslaughter.

The U.S. State Department says it regrets the Russian Parliament’s decision to pass the bill, saying it would prevent many children from growing up in families.

The passage of the bill follows weeks of a hysterical media campaign on Kremlin-controlled television that lambasts American adoptive parents and adoption agencies that allegedly bribe their way into getting Russian children.

A few lawmakers claimed that some Russian children were adopted by Americans to be used for organ transplants and become sex toys or cannon fodder for the U.S. Army. A spokesman with Russia’s dominant Orthodox Church said that the children adopted by foreigners and raised outside the church will not “enter God’s kingdom.”

Critics of the bill have left stuffed toys and candles outside the parliament’s lower and upper houses to express solidarity with Russian orphans, 46 of whom who were about to be adopted in the U.S.

Those children would remain in Russia if the bill comes into effect, Russia’s Children’s rights ombudsman Pavel Astakhov said on Wednesday.

Several international adoption agencies are based in the Atlanta area or have local branches.

Doug Mead, president of the Georgia Association of Licensed Adoption Agencies, which represents some 23 agencies, said it’s unfortunate that needs of orphans have ended up in the middle of a political dispute.

The president of Bethany Christian Services, William Blacquiere, said two families working with his agency were preparing to travel to Russia in January to finalize adoptions.

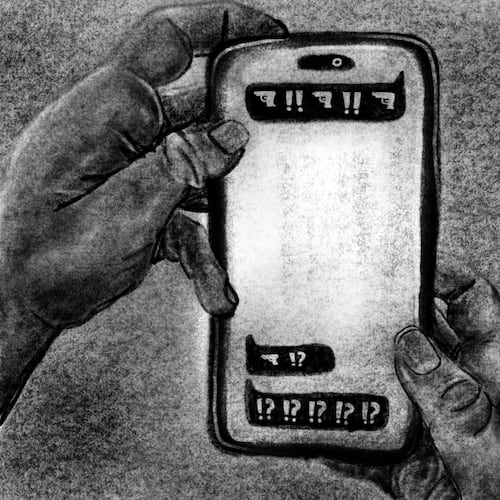

“It’s causing a lot of anxiety and concern, especially in the families that have been matched with a child and met the child,” Blacquiere said. “To them, this would be like losing the life of a child.”

Lisa Miller, 46, of Alpharetta, said she was “a little bit in shock and denial” when she learned of the impending shutdown on Russian adoptions. A single woman who works in the financial services industry, Miller started the process of adopting a child from Russia a few months ago. Miller hoped there would be less chance of getting passed over for a married couple or having the birth parents interfere if she chose international adoption. Now, Miller said she will consider other options, such as fostering a child domestically.

“I know I want to be a mom,” Miller said. “I’m not going to give up that hope.”

* Associated Press writer Nataliya Vasilyeva contributed to this story.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured