Oxendine caught up in lab testing dispute

Georgia’s former insurance commissioner John W. Oxendine says he walked away from a deal with a Texas company called Next Health that is embroiled in a $100 million fraud lawsuit playing out in Dallas.

But a paper trail that revealed Oxendine’s plans to work with the company is part of the ambitious civil case against Next Health filed by UnitedHealthcare, the giant health insurer that isn’t the first to allege a rip-off in the high-dollar lab testing industry.

The Texas case is a colorful one. United says Next Health made a fortune by giving gift cards to people who agreed to urinate in cups at a Whataburger restaurant. The lawsuit also says Next Health funneled kickbacks to medical providers to get them to order expensive tests that patients didn't need. The suit doesn't name Oxendine's International Medical Research as a defendant. But it alleges that Next Health set up a scheme to use International Medical Research as a conduit for its kickbacks.

Next Health is also dealing with drama outside of its $100 million civil dispute with UnitedHealthcare. The FBI raided one of Next Health’s offices last month. Plus, two of Next Health’s owners who were criminally charged in a massive healthcare fraud case in 2016 were arrested last month on charges that they smuggled medical marijuana from California to Texas.

Oxendine said he decided not to go through with a deal with Next Health because he had a bad feeling about the company’s executives. “We never did anything with them. Not one dollar — nothing,” said Oxendine, who served 16 years as Georgia’s insurance commissioner before he ran for governor in 2010.

“It looks like they were doing some shady stuff,” he said. “That’s why I walked away from these guys.”

But the idea of working together went far enough to create the paper trail showing what Oxendine and Next Health had in mind.

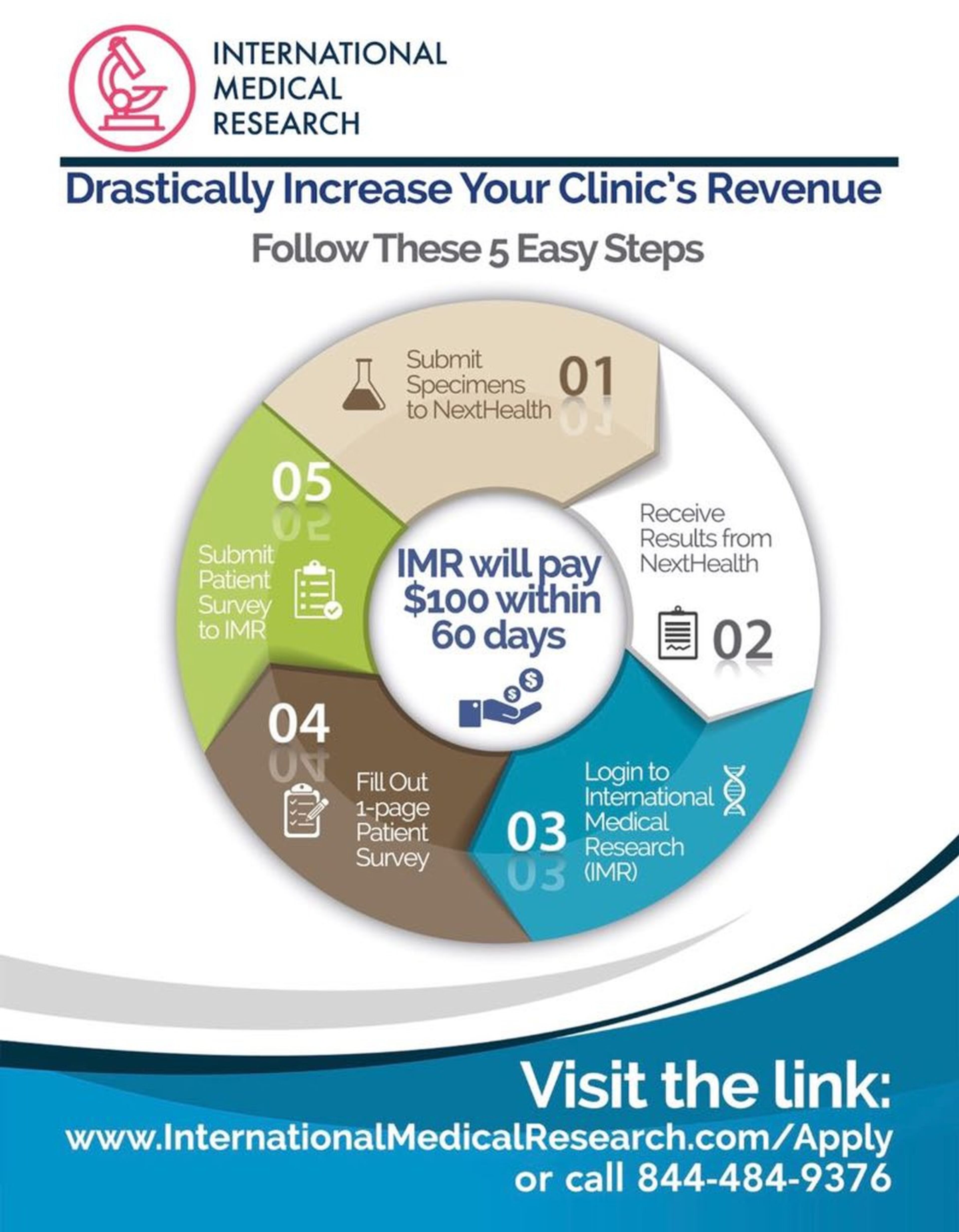

In marketing fliers, International Medical Research promised doctors “an extremely lucrative, new revenue stream.” Doctors who completed five “studies” a day would be paid $120,000 a year. One flier shown in the complaint features an image of dollar signs floating into an open hand and urges doctors to “Drastically Increase Your Clinic’s Revenue” by following “five easy steps” that involved sending specimens to Next Health and filling out a “1-page” patient survey.

Next Health does drug and genetic tests that can cost thousands of dollars each.

The lawsuit alleges such payments to doctors were just kickbacks and that Oxendine’s company was formed to be the cover for the scheme — a claim Oxendine said is unfounded.

Next Health has denied the allegations and characterized UnitedHealthcare’s lawsuit as a “shakedown” that seeks to drive Next Health out of business and allow the insurance giant to get back $100 million it paid for legitimate lab services.

The allegations and legal attacks won’t let up anytime soon. Last month, a judge ruled that United’s civil suit can move forward. In a statement, United said the decision will allow the insurer to “shine light on companies engaged in inappropriate lab services that put patients at risk and drive up costs.”

Oxendine: Insurer got it wrong

Questionable lab testing has been a recent focus of both prosecutors and insurers, with cases popping up across the country.

In Georgia, for example, federal agents raided a Gwinnett lab, Confirmatrix, in 2016. The company was indicted in Tennessee for what the government says were unnecessary lab tests on urine samples at pill mills as a way to overcharge the government and private insurance companies.

Blue Cross Blue Shield has filed a lawsuit alleging that a company that bought two rural Georgia hospitals was using them to reap more than $110 million in improper lab testing fees.

Oxendine told the AJC that the idea behind International Medical Research was to quickly collect the information needed to support the use of expensive lab tests in case an insurance company did an audit that questioned whether the tests were medically necessary. “As a lawyer, I routinely fight audits,” Oxendine said.

While insurance commissioner, Oxendine often took on insurers over how they handled reimbursements. During the 2000s, he fined UnitedHealthcare five times for being too slow to pay the medical claims of doctors and hospitals, including a $2.3 million penalty in 2005.

Under Oxendine’s idea for his company, doctors would be paid $75 to $100 to fill out three pages of information about the patient and the lab test, Oxendine said, not a single page as one flier suggested. Doctors were to be paid for their time, not for using Next Health as the lawsuit suggested.

Oxendine said UnitedHealthcare’s statement in the lawsuit that his company was created specifically to work with Next Health is false. State records show Oxendine’s company was created in April 2015. He said he didn’t meet with Next Health until 2016. International Medical Research was officially dissolved at the end of 2017.

UnitedHealthcare’s suit also got it wrong, Oxendine said, when it said his company was involved in both urine and saliva specimens. He said his discussions with Next Health related to genetic and cancer tests.

Oxendine said he believes United was confused about his company’s role when it filed the lawsuit in January 2017. “United’s comments in the complaint were made before United had any detailed information whatsoever,” he said.

UnitedHealthcare declined to comment about International Medical Research.

Fraud or legitimate medicine?

While Oxendine said the concept behind International Medical Research made sense, he said he wasn’t comfortable with Next Health’s executives.

“When I heard about the lawsuit and the feds it did not surprise me one bit,” Oxendine said.

Two of Next Health's owners — Semyon Narosov and Andrew Jonathan Hillman — are embroiled in other controversies alleging illegal payments. The two were among 21 people criminally charged in 2016 as part of a massive federal case that alleged a doctor-owned hospital paid million of dollars in kickbacks and bribes in exchange for patient referrals. Just last month, the FBI searched Next Health's Dallas offices as part of a kickback investigation involving pharmacies, according to the Dallas Morning News. And then there's the latest arrest, where the two men are accused of buying a medical marijuana business in California and illegally shipping marijuana to Texas.

The $100 million case mentions fraud and kickbacks, but it’s a civil case, not a criminal matter. At its heart, it’s the kind of business dispute over payments that plays out every day between medical providers and insurance companies.

Some of the accusations suggest outright fraud, especially United’s claim that Next Health’s sales consultants paid people $50 to urinate in a cup in the bathroom of a Whataburger, so the urine could be divided and sent to Next Health for expensive tests.

But other allegations revolve around whether tests ordered by doctors were truly medically necessary — a hot topic when it comes to high bills for lab tests.

In recent years, federal prosecutors have more aggressively pursued cases alleging kickbacks and lab testing fraud in government healthcare programs. In June, former executives of a New Jersey clinical lab were sentenced to prison after admitting to bribing doctors in a $100 million kickback scheme.

The government’s aggressive stance may be inspiring claims by private insurers, said Brian McEvoy, a former federal prosecutor who is now a private attorney in Atlanta with the Polsinelli law firm. He advises health care clients about fraud and abuse matters and compliance with regulations.

McEvoy said the federal Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits exchanging anything of value for referrals of business in federal health care programs such as Medicare. But it doesn't apply to private insurance plans. He also said the attack by an insurance company over claims for lab testing gets into a sticky issue of whether a doctor or an insurance company gets to decide what's medically necessary.

It’s one thing if someone is billing to test a specimen collected in a restaurant bathroom without a doctor’s order, he said, but it’s another when an insurer is objecting to a claim where a doctor found that certain lab tests were medically necessary.

“These large for-profit payors have become more forceful in protecting their bottom line, even if it means going after providers as they have here,” McEvoy said.

McEvoy said the wording in the marketing fliers about Oxendine’s company may not have been ideal, but he said it’s not improper or illegal to contract with doctors to provide information used in medical research as long as the services provided to patients were medically necessary and actually provided. This is true, McEvoy said, even if the relationship results in patient referrals.

About John W. Oxendine

The Republican was first elected Georgia’s insurance commissioner in 1994 when he upset Democratic Georgia Insurance Commissioner Tim Ryles. Oxendine then stayed in the public eye by selling himself as a consumer advocate. He won re-election in 1998, 2002, and 2006 before deciding to run for governor in 2010. Oxendine was seen as the front runner in the 2010 governor’s race but failed to deliver on primary election day.

He continued to attract attention after leaving office.

The AJC reported in 2011 that on his last full day in office as commissioner, he issued himself licenses to sell insurance and adjust claims. Oxendine did not take the mandated classes or licensing tests, using his authority as insurance commissioner to waive the requirements. Lawmakers filed legislation to outlaw the practice.

In 2015, the state ethics commission rekindled an ethics case against Oxendine’s 2010 campaign after the AJC reported that he had failed to return more than $500,000 worth of leftover contributions from his gubernatorial bid and that he spent money raised for the Republican runoff and general election campaigns that he never ran because he lost in the GOP primary.

The commission filed new charges, and Oxendine amended reports to show more than $700,000 left over, including $237,000 in loans to his law firm. That led to more charges last year alleging that Oxendine illegally benefited personally from the law firm loans.

Under state law, candidates can’t use campaign funds for their personal benefit. They money can only be used for campaigns or maintaining the office they hold.

Some of the charges in the commission’s complaints were dismissed in late 2015 but others are still ongoing. Oxendine fought the commission for months in court, trying to prevent investigators from getting copies of his law firm’s bank records, but he lost the case.