As COVID, flu and RSV cases continue to sicken thousands and fill hospitals around the country, a leading scientist who has worked for years on vaccines for all three viruses believes vaccines for RSV are possible as early as May.

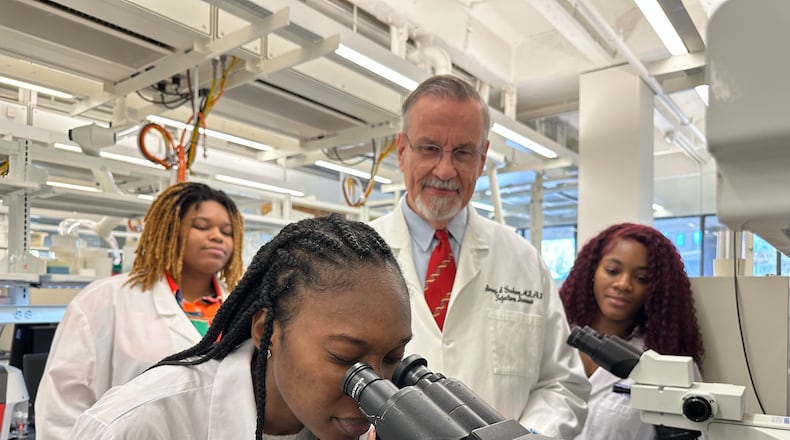

Dr. Barney Graham, a clinical trials physician, immunologist and virologist — now a professor at the Morehouse School of Medicine — says several RSV vaccines are in late stages of development, nearing final approval by the Food and Drug Administration. Graham spent most of his career at the National Institutes of Health, retiring in September 2021 as deputy director of its Vaccine Research Center.

“There are several vaccines now in front of the FDA that hopefully would be evaluated and approved by next summer, before the next season,” Graham said.

Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, is a common respiratory virus and is the leading cause of hospitalizations for infants in the United States. According the the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 58,000–80,000 children younger than 5 years old are hospitalized with RSV each year, especially dangerous for premature and medically fragile babies.

In addition to infants and young children, older adults are most at risk for severe RSV infections and deaths. CDC says 60,000-120,000 older adults in the U.S. are hospitalized and 6,000-10,000 die from RSV infection. Those at highest risk for severe infection are seniors, especially those 65 years and older, adults with chronic heart or lung disease and adults with weakened immune systems.

Graham says the work that he and his NIH colleagues did on RSV has led to protein-based vaccines being in late-stage testing that could result in vaccine available by next winter’s RSV season. Vaccines are being developed by several pharmaceutical companies, including GSK, Pfizer and Moderna.

The first vaccines are expected to target adults over the age of 60, those with risk factors and pregnant women aimed at protecting their unborn infants up to 6 months of age.

“They’re all using the protein design that we developed 10 years ago,” Graham explained.

Graham joined the Morehouse School of Medicine faculty as a professor last May and serves as a senior advisor for Global Health Equity in the office of MSM president and CEO Valerie Montgomery Rice.

Credit: Morehouse School of Medicine

Credit: Morehouse School of Medicine

“I wanted to be at Morehouse to work on vaccine equity,” he said. “That means not just who gets access to vaccines or doesn’t, but also on vaccine uptake.”

Graham said he was attracted by MSM’s reputation for community engagement and education, especially in providing care for rural communities in Georgia. He cited the medical school’s work to reach the Black community and encourage people to get vaccinated during the height of the pandemic.

“They’re the only medical school I know that has the word ‘equity’ in their mission statement. Everything that Morehouse does is about health equity and trying to better serve the underserved,” he said. “It’s just the way the whole place operates.”

Graham began working on RSV at the NIH in the mid-80s, spending the first 20 years of his career understanding why RSV vaccines had failed and how to make them safe. Graham continued working on this front throughout his tenure at the NIH, focusing on how to make RSV vaccines safe, effective and available.

He said that this year’s outbreaks of RSV and other respiratory viruses have been influenced by shifts in exposure that resulted from the pandemic.

During earlier stages of the pandemic, he explained, many younger children were more isolated than in typical years. School-age children were learning virtually, so there was less of the virus circulating around. In effect, decreased immunity from less exposure changed when the virus appeared in the population, Graham explained.

Now, with the easing of pandemic protocols such as masking and social distancing, a surge in respiratory viruses has occurred.

“Instead of a yearly cycle, we’ve had these 18-month cycles, so we don’t really know why the disease is so bad this year,” he said. “With these big gaps, we’re now having one of the bigger outbreaks that we’ve seen over the last many years.”

Graham also said that “viral competition” — a phenomenon when one virus is circulating widely in a population, making it harder for other viruses to break through — could also be the cause for the change in outbreaks.

Awareness of the RSV virus has increased with this year’s outbreak, something that Graham says can be tied to how doctors and health organizations communicate to patients.

“We’re all infected with it by the age of two, and we all get re-infected throughout our lives,” he said. “When we’re older, it causes a lot of excess mortality and hospitalization.”

He says there is a chance that other respiratory viruses such as influenza have overshadowed the public’s general knowledge of RSV.

“I’m hoping that people will now realize that RSV is a problem. It’s always been a problem,” Graham said. “Now, that we’ve been through COVID, I think what they’re realizing is, there’s more than just one respiratory virus problem.”

Bringing any vaccine to production and distribution is usually a costly, years-long effort, with trials required to ensure safety and effectiveness. In the case of RSV vaccines, the NIH studies that indicated strong RSV protection resulted in FDA fast-tracking the review process.

The RSV vaccine research has taken years, with disappointments — even failure — along the way. Graham recalled a major setback in the 1960s, when scientists attempted to take the same approach successfully used in polio vaccines developed by virologist Jonas Salk. Salk’s method used formaldehyde and heat to kill the poliovirus while keeping the properties that trigger a response from the immune system.

Children who received the early RSV vaccines, however, ended up sicker because they had received an enhanced version of the virus. That stopped vaccine development for RSV.

Now, more than 50 years later, the current RSV vaccine formulation is similar to the spike protein used in COVID-19. A protein found on the surface of RSV, Protein F, has been used in the latest vaccine development for RSV. With using this protein in vaccine develop, scientists are able to generate immune responses that provide protection from the virus.

“Should the vaccine be judged to be safe and efficacious and approved by the FDA in the May timeframe, we are on target to make sure that this vaccine is available for patients to begin the RSV season in 2023,” said Leonard Friedland, director of scientific affairs and public health for GSK’s vaccine division, said.

“The whole scientific community for more than 50 years has been trying to develop vaccines for RSV. I think we’re finally there.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Report for America are partnering to add more journalists to cover topics important to our community. Please help us fund this important work at ajc.com/give

About the Author

The Latest

Featured