Atlanta-based Norfolk Southern faced tough questioning at a federal hearing this week about how it handled the Feb. 3 derailment of a train carrying hazardous chemicals.

The National Transportation Safety Board brought the two-day inquiry to East Palestine, Ohio, the town that has lived with the consequences of the wreck and fiery explosions. Officials questioned why the railroad’s detection systems and inspections didn’t prevent the derailment on the edge of the small town.

The derailment of 38 railcars caused no deaths or injuries, but forced evacuations of residents in the area and prompted many to report troubling symptoms and lasting fears about their long-term health, property values and future. Norfolk Southern in April cited initial costs estimated at $387 million due to the derailment, including cleanup, a preliminary estimate of legal claims and settlements and other costs.

The transportation officials also asked about Norfolk Southern’s cutbacks to its maintenance staff over the years and pressure on workers to conduct inspections more quickly.

A technical expert testified that newer acoustic detectors — which are not yet in widespread use — could better find defects to prevent derailments than the heat detectors more commonly used along rails.

NTSB officials questioned Norfolk Southern about why some first responders didn’t quickly get information about the hazardous chemicals on the train when they responded to the derailment the night of Feb. 3.

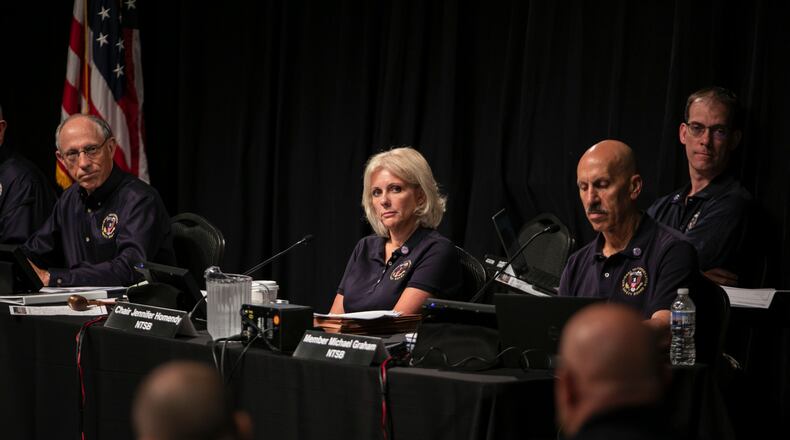

“The information learned during this hearing will help us determine what went wrong on Feb. 3,” said NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy. “We’ll then make safety recommendations to prevent similar derailments from ever happening again. And we’ll advocate for our recommendations for as long as it takes.”

Norfolk Southern, which has its headquarters in Midtown Atlanta, faces multiple lawsuits over the derailment.

The railroad said it has taken actions to improve its safety culture, including adding more detectors and studying new technology.

“We take these opportunities to learn and that’s how we get better,” said Jared Hopewell, an assistant vice president at Norfolk Southern, on Friday.

The company has also committed to helping East Palestine bounce back from the disaster, working to remove contaminated soil and water and pledging more than $62 million to the area.

The NTSB also questioned why rail officials decided to burn railcars of toxic vinyl chloride days after the crash, causing a large and noxious black plume of the burning chemical over the town — even though a supplier had told Norfolk Southern it did not believe there was a chemical reaction in the cars posing risk of an explosion.

Key officials who decided to do the “vent and burn” procedure did not know about the supplier’s perspective, but said it may not have changed the decision. Officials said the decision was also based on other factors, including risks from flammable gas. The incomplete information was one of a number of communication problems spotlighted during the hearing.

The derailment led to one of the biggest evacuations from a U.S. rail accident in years. State and federal officials have indicated the air and water are safe. But there are residents in the area who have fears about the long-term impact to their health from the chemicals released, including the vinyl chloride, which in the long term, with severe exposure, can cause several cancers.

“The train derailment has quite frankly changed East Palestine forever, has disrupted lives, impacted businesses and created uncertainty,” said East Palestine fire chief Keith Drabick during his testimony.

Homendy said it’s rare for the agency to hold field hearings, but the proceedings were held in East Palestine instead of Washington, D.C., because “the people affected by this derailment deserve as much insight as possible” and “so members of the public can hold the NTSB accountable for conducting a fair, thorough and independent investigation.”

Homendy questioned Scott Deutsch, a regional manager of hazardous materials for Norfolk Southern, about why there was a delay in getting information about the train’s contents to firefighters and others who had to figure out what kind of fire they were facing and how to protect their crews.

Homendy said Norfolk Southern quickly sent an email with the information about the train’s freight to its own contractor that handles air monitoring. Some emergency responders on the scene received the information earlier, while others received it later.

Deutsch said he said he sent the information to a county emergency management agency director while he was en route to the scene.

In the wake of the derailment, Drabick, the fire chief, testified that he “absolutely” has concerns about the impact of the burning chemicals on the health of his firefighters.

“I’m concerned about not only my responders but everybody around for long-term health concerns,” Drabick said.

NTSB hearing on East Palestine derailment

The hearing focused on:

Timeline of emergency response

Hazard communications on scene

Emergency responder preparedness and training

Vinyl chloride and decisions to burn

Freight car wheel bearings

Defect detector systems

Hazardous materials tank cars

Tank car derailment damage, crashworthiness

Source: NTSB

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured