Author at Atlanta event: How Stonewall kick-started the gay rights movement

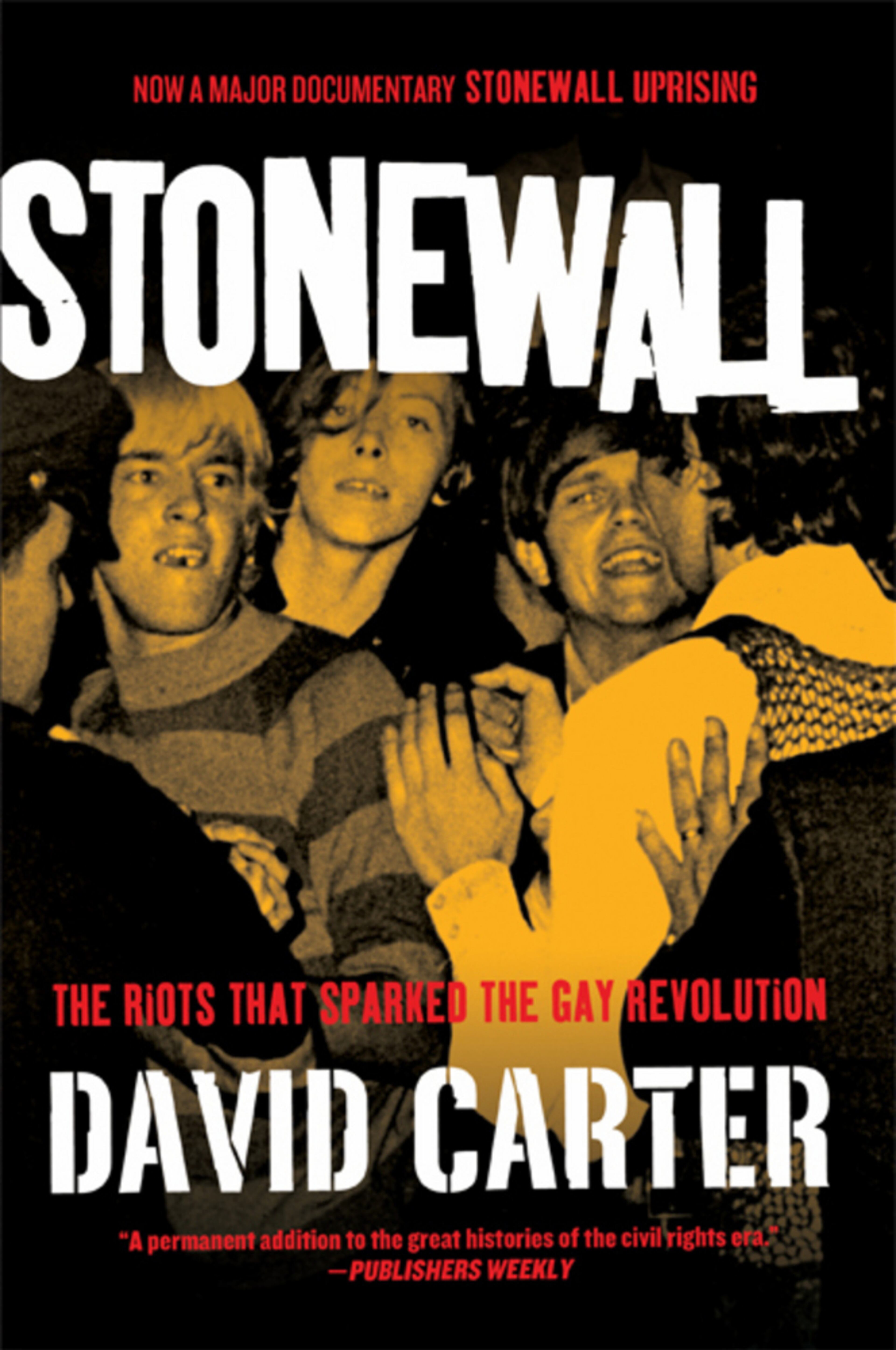

David Carter, who chronicled a turning point in American civil rights with his book, “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution,” was a teenager pursuing a science summer program at the University of Georgia in the summer of 1969.

He remembers hearing a news announcer, perhaps Walter Cronkite, give that day’s riot in Greenwich Village a brief mention, but “at that time I didn’t know I was gay, so it didn’t mean much to me.”

Yet the demonstrations that followed the uprising at the Stonewall Inn, the formation of the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance, the first Gay Pride march that took place on the one-year anniversary of the uprising, all had a profound effect on the young man.

Fifty years later author Carter reminisced about how the reverberations from that event even rolled down to Jesup, Georgia, where he attended Wayne County High School.

“These people went against every idea I had of homosexuality. These people looked normal, young, happy, nice-looking,” he said.

“And there was this militancy, but it was a beautiful militancy, not a hate-filled militancy. All that to me was very winning.”

The same realization was happening to the rest of the country, Carter said. The American public was discovering that gay people looked just like them.

Carter, 66, spoke Friday at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, in a presentation organized by Bank of America and Cox Enterprises to commemorate the Stonewall anniversary.

The presentation, which was followed by a panel discussion, began with a short documentary film, with news footage from the time.

Among the scenes from the era was a much younger Mike Wallace reciting the findings from a survey on homosexuality. “Most Americans,” he tells the camera, “look on homosexuals with disgust or fear.”

The Stonewall Inn was a Mafia-run bar that catered to a gay community in Greenwich Village that had few choices of places to gather.

“It was dirty, and sold questionable Mafia alcohol,” said Carter.

It had no liquor license, and was often raided, but because the owners paid protection money to the police, they were usually able to warn the patrons ahead of time.

Early in the morning on June 28, 1969, the police staged a raid with no warning.

Instead of dispersing, and heading home to avoid being recognized or photographed, this time the crowd stayed around. At first they ridiculed the police, but when one of the female patrons was handled roughly, something clicked.

The crowd began pelting the police with bottles and bricks.

The officers retreated to the interior of the bar, but the rioters pried up a parking meter and used it as a battering ram.

Unrest continued for six days. Gay patrons decided that they’d had enough harassment.

“Whose streets are these? These are our streets,” John O’Brien, a participant in the riot, told The New York Times later.

“It inspired the creation of a new face for the movement,” said Carter. “Progress happened in New York.” he said. Police stopped using “decoys” to entrap gay New Yorkers. Gay bars became legal.

“We’re very proud of David,” said his older brother Bill Carter, who attended the speech.

Bill, who introduced his younger brother to the poetry of Rimbaud and the opera of Anna Moffo, was perhaps the ideal older brother for a gay kid from a little town in Georgia.

David came out to his brother Bill and Bill’s wife, Lynn, during a trip to Paris, where they were safely distant from Jesup.

David Carter said the current era represents a threat to the freedoms of the LGBT community, but that gay people and their allies should remember the humor of the early Pride parades and temper their fervor.

“We have to be careful not to be self-righteous, not to be judgmental. We need to use a little more tact, a little more kindness, a little more sensitivity.”