Pej Mahdavi rises each morning to tamp down volatile, often dangerous situations in Gwinnett County.

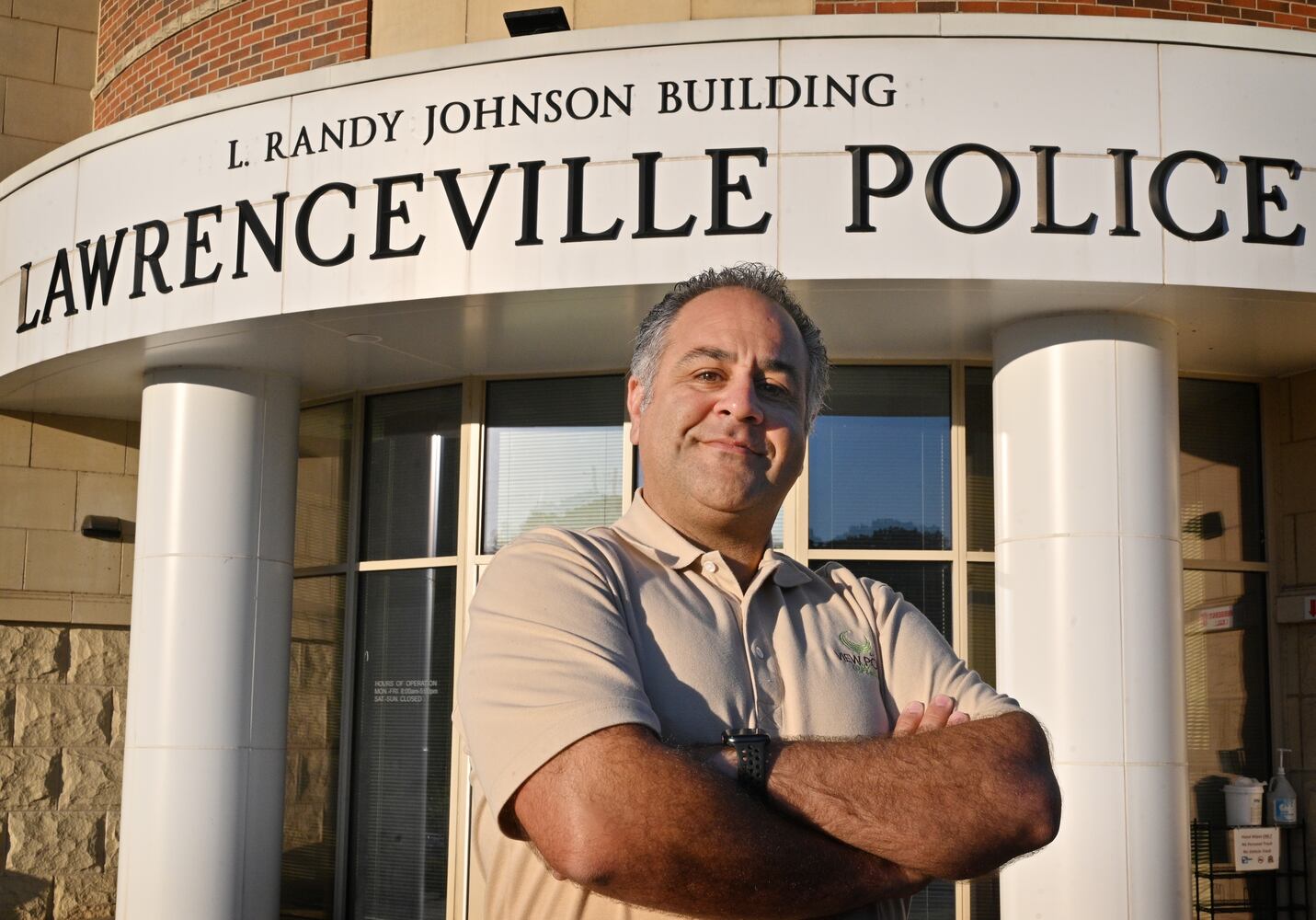

The 43-year-old Lilburn man may work out of a police station and ride in a patrol car, but he isn’t an officer. The father of two is a licensed behavioral health clinician who works with law enforcement agencies on mental health crises.

Mahdavi is part of a movement by local jurisdictions to explore new ways of policing. Cases of police brutality, including the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minnesota officer last year, set off a wave of calls to “defund the police.” Some activists demanded reducing overall police budgets, while others said to redistribute dollars toward other initiatives.

Following an uptick in violent crime during the pandemic, some of the largest police agencies in metro Atlanta increased their police budgets instead of slashing them, according to data examined by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. But some local leaders are using the additional funds to try less adversarial means of enforcing the law.

Lawrenceville and Gwinnett County started sending out clinicians this summer to respond to crises alongside officers, borrowing the framework for “co-responder models” from other communities such as Brookhaven, Conyers and Johns Creek. The clinicians connect individuals with treatment, counseling and other resources.

The new program is working well, said Lawrenceville Police Chief Tim Wallis. He added that more than 100 people avoided jail time by the end of September due to the addition of clinicians.

“I always tell people that criminal justice reform is coming,” Wallis said. “Having been in law enforcement for 30 years, a lot has been put on law enforcement to handle — mental health, substance abuse and homelessness.”

These issues started landing on cops’ shoulders a few decades ago, even though they weren’t equipped to handle them, said Dean Dabney, a professor who chairs the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Georgia State University.

Shifting responsibilities from cops to others trained to handle them, like social workers, can allow police departments to more efficiently do their jobs, Dabney said. Co-responder models can also help reduce “frequent flyers” — individuals who law enforcement encounter over and over — by directing them to counseling or other mental health services, he said.

DeKalb County has received national recognition for its public safety efforts over the past year. President Joe Biden mentioned how the county’s police department used federal COVID-19 relief funds to start several initiatives, including many that focus on mental health, violence prevention and alternative policing.

Michael Thurmond, the county’s CEO, said the programs aren’t a direct response to the defund the police movement, but he said they do address some concerns by activists. He said drastically decreasing police spending while hoping for police reform is a “false narrative.”

“It’s not an either-or proposition,” Thurmond said. “What we’re doing is increasing funding for violence intervention strategies with the availability of federal funding. You don’t have to make the choice. You can actually do both.”

The county is using about one-third of its American Rescue Plan Act dollars to fund training courses, bonuses for officers to boost retention, license plate readers, drones and a court program for young, first-time offenders.

“This is the way of the future,” said Mahdavi, who serves as a clinician for GCPD and oversees the co-responder program in Lawrenceville. “... If somebody has a challenge, they didn’t choose it. It’s our job to step up and help those folks.”

Alternative response units can lower instances of use of force and allow officers to focus on more critical issues like homicide investigations, said Tiffany Williams Roberts, an Atlanta-based civil rights and criminal defense attorney who works at the Southern Center for Human Rights.

“Often, people in communities would prefer violence de-escalation or for a mental health provider to come out over police to come out,” Roberts said. “... People who are in mental health crises or are going through withdrawals related to substance abuse — policing doesn’t address their anatomical and physiological needs in the same way that service providers can.”

Like Lawrenceville, Cobb County police use a crisis intervention team of two officers paired with mental health professionals. It also uses license plate reading cameras to find wanted vehicles and suspects.

The defund movement had little effect on the county’s officers, as the department already has social programs, partnerships and specialized units to promote less violent ways of enforcing the law, said Wayne Delk, spokesman for the department.

The Marietta Police Department requires all new officers to go through Brazilian jiu-jitsu training once a month to emphasize the use of hand-to-hand tactics when possible. As an alternative to reaching for a taser or handgun, some officers also carry shotguns to fire less-lethal beanbag rounds.

Officers recently used beanbag rounds to arrest a homeless man who stole an axe and hatchet from a Cobb Parkway store. The man wandered over to a car dealership near potential buyers and wouldn’t drop the weapons, leading them to fire four rounds at his extremities and one at a car.

The department tries to build trust through community outreach and being transparent on social media, said Chuck McPhilamy, public information officer for Marietta police. “Good, bad or ugly — if we make a mistake, we’ll tell you,” he said. “If we haven’t, then we’re going to tell you what really transpired.”

Police officers need to be held accountable through civilian oversight, Roberts said, rather than rely on law enforcement to monitor its own actions.

Police are vital to a properly functioning society, said Marietta Police Chief Dan Flynn.

“Thus, to us, the idea of defunding the police is unthinkable and extremely ill-advised,” Flynn said. “We should be fairly accountable for our actions, but the idea of eliminating is strange at best.”

Spending dollars on police isn’t as effective as spending them on the underserved, Roberts said. Violent crime could be curbed by bettering the socioeconomic status of residents, she said, placing an emphasis on prevention instead of punishment.

“If we complain about officer morale, workload and understaffed departments, then it seems to me we would embrace things that lighten the load of law enforcement instead of rejecting it as being deprivation,” Roberts said.

AJC staff writers Matt Bruce and Zach Hansen contributed to this report.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured