It was March, a dozen years ago, the middle of the night in Morocco and the visiting chief executive and chairman of Coca-Cola woke, checked his phone and was hit with news of an earthquake that had killed thousands and unleashed radiation from a nuclear plant in Japan, one of Coke’s largest markets.

Muhtar Kent showered, dressed and called two of the company’s directors. One was James D. Robinson.

“It was three in the morning, late evening in the U.S.,” Kent recalled recently. “I asked them to come with me to Japan the next day. When I asked Jimmy, he didn’t say, ‘When? How?’ He said, ‘I’m coming with you.’ That is the kind of guy he was.”

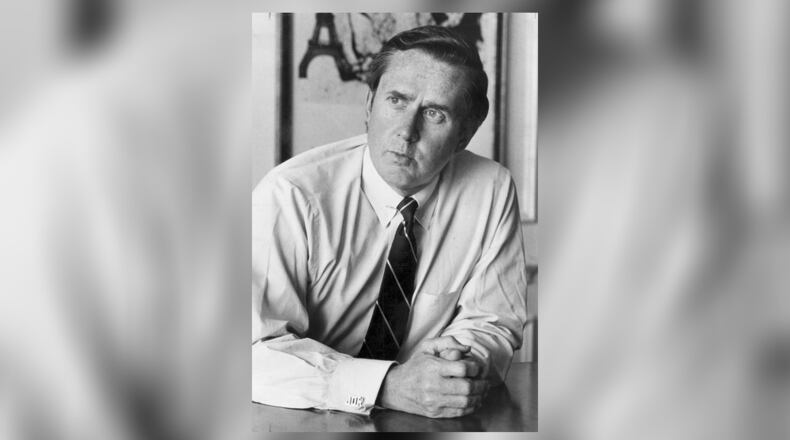

James D. Robinson III, 88, died March 18 of respiratory failure from recurrent pneumonia, according to a family spokesman.

And while he passed away in New York, where he had settled and built a legendary corporate career, ties to his hometown were lifelong and his death has drawn warm and respectful praise from some of the iconic institutions he had embraced.

Although he accumulated wealth and power and was a key force in changing the rules for Wall Street, Robinson is remembered in Atlanta for his manner, his mind and his character — oh, and a handshake like a vise.

As a director of Coca-Cola, he was often part of high-stakes discussions in which the company’s future was on the line. Robinson was a force for stability and maturity, dependable and mild, but he was not a pushover for management.

In the end, he saw the future as well as anyone, said Kent, who retired from Coca-Cola in 2019.

More than most, he saw how important it was to go digital.

The company’s current use of artificial intelligence can be traced to the meetings in which Robinson prodded executives to invest in technology, he said. “This is a very long road. It is very easy to get off course, but if you stay the course, you reap the rewards.”

Yet his first association is not with Robinson’s far-sightedness, business-acumen or intellectual firepower, Kent said.

“If you say, ‘Give me one trait of Jimmy,’ I would say that he made people comfortable,” Kent said. “And that was whether you were chairman of the board or you were a little employee walking the corridors. He would make you comfortable.”

In Japan, the top Coke leaders offered support for customers and employees and they promised help in the rebuilding of damaged schools. In Tokyo, they felt frighteningly strong aftershocks. When the trio of Coke leaders met the head of one of their biggest customers, Kent recalled, “He expressed his amazement and huge surprise that two of our directors had joined me on such a journey and the rapidity of our arrival.”

In making his career in finance, Robinson was following a well-worn family precedent.

Robinson’s father was chief executive and chairman of First National Bank of Atlanta, an institution that through acquisitions became Wachovia and later Wells Fargo. His grandfather had held the same positions, and his great-grandfather was the founder of First National’s predecessor institution, Atlanta National Bank.

His mother, Josephine Crawford Robinson, was an active philanthropist, who was involved with a number of social organizations in Atlanta.

Robinson graduated from Woodberry Forest School in Virginia, and in 1957, from the Georgia Institute of Technology. He spent two years in the Navy, then earned a master’s degree in business from Harvard and moved to New York.

He worked at two Wall Street firms, then moved to American Express, rising quickly through the ranks to become chairman and chief executive at age 41.

He supported a broad deregulation in 1999 that led to some financial innovations that were blamed — at least in part — for the housing market bubble and the financial collapse in 2008.

According to the New York Times, Robinson later acknowledged that financial deregulation “went too far,” but he did not argue for a return to the previous restrictions.

Robinson also said he had a “give back” ethos learned from his parents, serving for nearly a half-century on the board of trustees for the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. He volunteered for a number of other organizations

He was on the Coca-Cola board for more than three decades, which is where Helene Gayle met him. She is now president of Spelman College, but back then, she was a bit intimidated.

“Coca-Cola is a pretty powerful board,” she said. “He helped me to appreciate that although I did not have a lot of experience in business, that I still had something to offer.”

She was surprised by his demeanor.

“He was such a humble guy for somebody who had all that he had and had lived in the worlds in which he lived,” Gayle said.

Through years of discussions, arguments and decision-making, she saw continuity of Robinson’s character, she said. “He wasn’t somebody that needed to be the loudest voice in the room. He was judicious in what he said, so that when he spoke, you listened.”

She also served with him on the board of the Brookings Institution. She saw him interact with servers at meals, with blue- and white-collar employees in the hallways.

“He would say ‘hi’ to the workers,” she said. “He was the same person, no matter where he was.”

Born in 1935, Robinson came of age when Jim Crow laws still ruled the South, segregation was accepted practice and few Blacks voted. As the Civil Rights Movement gained strength, many of his contemporaries fought to prevent change.

After becoming the top executive at American Express, Robinson was asked by Spelman’s then-president, Donald Stewart, to chair a fundraising campaign, the first ever for Spelman. A 2009 analysis of the college’s finances by investment advisers at The Common Fund said Robinson “was instrumental to the success of the drive because he used his extensive contacts in the corporate world to greatly expand the campaign’s reach and build awareness of Spelman College among the upper echelons of corporate America.”

To Gayle, the work with Spelman dovetailed with Robinson’s personal relationships, emerging from an interplay between the time in which he was raised and the values he was taught.

“As a gentleman of the South growing up in a certain era, Spelman was very important to him,” she said. “And it was important to him that he showed that I, as a younger, Black woman, that I was a valued individual.”

Robinson could easily have emerged from his relatively privileged childhood to be disdainful of people who were different. Many did. But in corridors, corporate dining rooms and conversations, Robinson made it clear where he differed from many of his white, gentry-raised peers, Gayle said.

“It was important to him that he show that wasn’t who he was,” she said. “Even though it was what he could have been.”

Public funeral services are set for 12 noon May 2 at Westview Abby Chapel, Westview Cemetery, Atlanta. Archbishop Foley Beach of the Anglican Church in North America will officiate.

Credit: NYT

Credit: NYT

Credit: NYT

Credit: NYT

Credit: NYT

Credit: NYT

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured