A ‘triple-dip’ La Niña is likely. Here’s what it means for Georgia

The heat that Georgia felt in the first half of 2022 is likely to linger into early fall and possibly beyond, a new federal forecast shows.

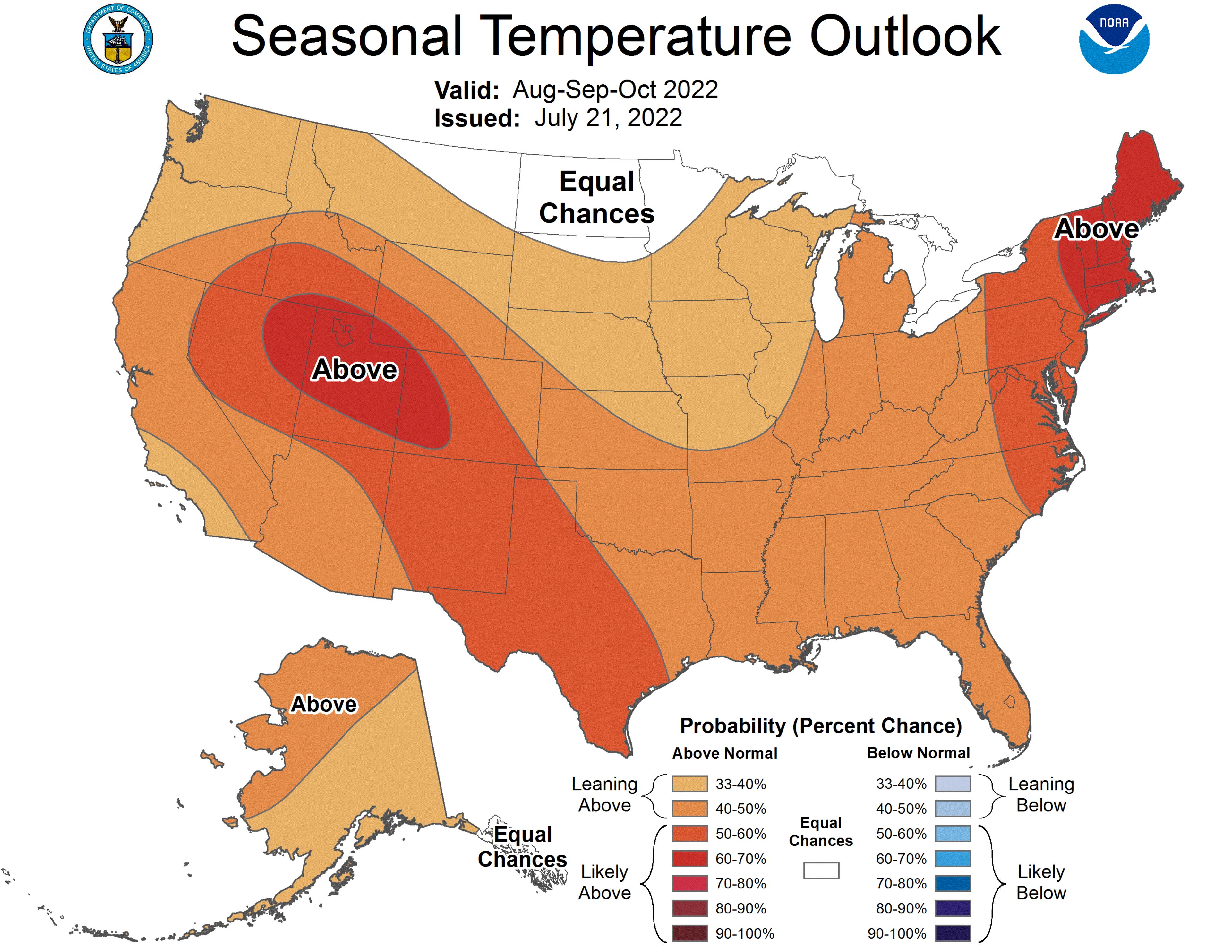

Odds are favoring hotter than average temperatures across Georgia and much of the continental U.S. through October, according to projections released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The forecast also shows that the next three months are likely to be wetter than normal for much of the state.

The first six months of 2022 were the 4th hottest such period for Atlanta in more than 90 years of record-keeping. And for Georgia as a whole, the first half of 2022 was the 16th hottest start to a year on record.

Georgia’s abnormally high temperatures so far this year and those likely in the months to come reflect the strong influence of climate change, said Pam Knox, an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia. The planet has warmed by roughly 2 degrees since 1880, and globally, the first half of 2022 was the sixth hottest on record.

“Every month for the foreseeable future, the chances are being pushed towards having above normal temperatures,” Knox said. “The temperature outlook ... is probably mostly related to climate change and things generally getting warmer.”

Looking ahead to the fall and winter, a persistent La Niña pattern is also likely to keep Georgia warm.

La Niña is a phenomenon driven by temperatures in the Pacific Ocean that influence weather conditions across the globe. La Niña typically brings drier, warmer conditions to Georgia and the southern half of the U.S. and wetter weather to the northern half, while its opposite – El Niño – triggers hot and dry conditions in the northern states, and an increased risk of flooding in the south. El Niño and La Niña episodes usually last between nine and 12 months, but can occasionally last for years, according to NOAA.

La Niña is also linked to active Atlantic hurricane seasons and is part of the reason NOAA has forecast more storms than usual this season.

NOAA’s latest forecast shows it is likely that La Niña will persist into fall and possibly into winter next year. If it does, it would be the third consecutive winter to feature La Niña conditions, an occurrence some meteorologists have dubbed a “triple dip” La Niña. While not unheard of, this so-called triple dip has only happened twice since 1950, NOAA says.

And while few Atlantans are likely to complain about the possibility of being spared chilly temperatures thanks to La Niña, abnormally hot winters are problematic for the state’s farmers, especially fruit growers.

Many of Georgia’s most profitable fruit crops, like blueberries and peaches, won’t bear fruit if they don’t get enough hours in the cold. At the same time, too much heat early in winter can trick the plants, causing them to develop earlier than normal and leaving them vulnerable to a winter freeze, like the one that wiped out many Georgia blueberry farmers’ crops last year.

If this forecast for another La Niña winter holds, Knox says it could cause more headaches for Georgia farmers.

“It could certainly happen again this winter. We’ll just have to see,” Knox said.

A note of disclosure

This coverage is supported by a partnership with 1Earth Fund, the Kendeda Fund and Journalism Funding Partners. You can learn more and support our climate reporting by donating at ajc.com/donate/climate/

More Stories

The Latest