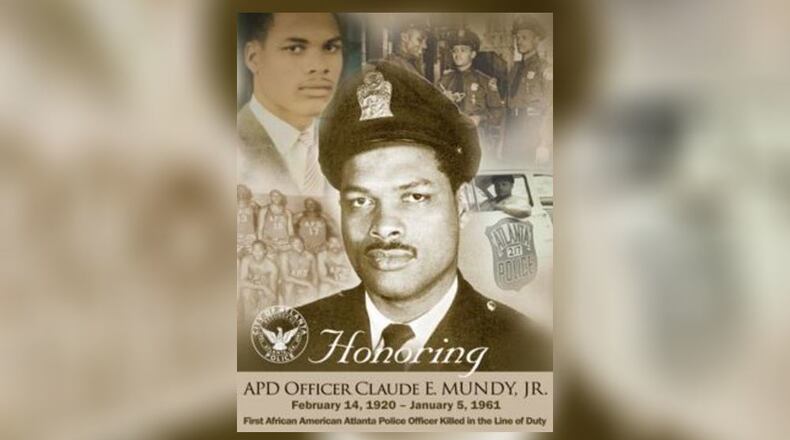

When Claude Mundy Jr. joined the Atlanta Police Department, segregation was still in full force.

He wasn’t allowed to get dressed alongside his white colleagues. Instead, he had to change into uniform at the Butler Street YMCA before reporting for roll call at the start of each shift. The department’s first Black officers also weren’t allowed to arrest white people and were initially prohibited from carrying guns.

But that didn’t stop Mundy from signing up to become one of the department’s first Black recruits, his family said. He was determined to make a difference and help keep his community safe.

Mundy was shot to death Jan. 5, 1961, while apprehending a burglary suspect inside a two-story apartment building, the first Black Atlanta officer to be killed in the line of duty. He was 40.

After being shot in the heart and falling to the ground, Mundy managed to pull his service weapon and shoot the suspect five times, killing him as well.

On Tuesday, Mundy’s surviving family members and the department’s top brass gathered at the officer’s northwest Atlanta gravesite to commemorate his sacrifice at a memorial service six decades overdue.

Among those in attendance were Mundy’s two surviving children, most of his eight grandchildren and some of his 23 great-grandkids.

Credit: Shaddi Abusaid / shaddi.abusaid@ajc.com

Credit: Shaddi Abusaid / shaddi.abusaid@ajc.com

Marilyn Mundy-Woods was just 5 when her father was killed. The youngest of five siblings, she regularly ate dinner with her dad ahead of his evening shifts and often hounded him to take her to work with him.

One day he caved and carried her to the precinct, though he instructed her to remain outside the room during roll call. It’s a day she still remembers vividly.

“He had been promising me for weeks and months, and that day, I just demanded to go,” she said.

As she waited outside the room pouting, a man approached her and asked who she was.

“He said, ‘Whose pretty little girl is this sitting out here?’” her son, Dante Woods, told the crowd. “She said, ‘My daddy brought me to work, but his mean old boss won’t let me come in this room with him and I’m upset.’”

The man then picked her up and carried her into the room full of officers before asking which policeman was her father. Marilyn Mundy-Woods didn’t know it at the time, but the man speaking was Herbert Turner Jenkins, APD’s former police chief and her father’s “mean old boss.”

Mundy, who stood nearly 6-foot-6, rose to his feet and sheepishly claimed her, she said. The chief told Mundy that from then on his daughter was allowed in the precinct anytime she wanted. Jenkins also gave her $2 and told Mundy to take her by the ice cream shop on his way home.

The story prompted a roar of laughter from the family members and officers who gathered Tuesday to commemorate Mundy’s life.

He was remembered as a great cop who loved his community almost as much as he loved his family. He loved to fix cars, his daughter said, and hoped to one day open his own diesel mechanic shop. The two were nearly inseparable, Marilyn Mundy-Woods said, recalling all the times her dad would invite her to slide underneath cars and trucks as he repaired them outside their home.

“No matter what it was, if it was for the love of his family, he did it,” said Woods, who never got the chance to meet his grandfather. “He was dedicated to this city and I’m sure he would have been very proud of the way this department has evolved.”

Interim police Chief Rodney Bryant said it was important to recognize Mundy’s sacrifice to the city and the police department.

“His memory and his efforts back then continue to bring us forward, even to this day,” Bryant said, acknowledging that it has never been easy to be a cop, let alone an African American officer at the height of Southern segregation. “We’re no longer looking at firsts because of him.”

Today, Bryant said, Atlanta’s police force is nearly 60% black, much more reflective of the communities it serves.

Atlanta Councilman Michael Julian Bond commemorated the anniversary of Mundy’s death by reading a proclamation from the city and presenting it to his family.

Bond, the son of civil rights activist Julian Bond, said Mundy was killed at the height of Atlanta’s student movement to desegregate the city. At the time, he was tasked with defending people who “wouldn’t share a sandwich with him, wouldn’t even sit next to him.”

He said he couldn’t begin to imagine the abuse Atlanta’s first Black officers must have endured as they patrolled city streets in uniform — getting spat on or called the N-word by some of the very residents they took an oath to protect.

“As the city’s first African American police officer to lose his life, this is a recognition that’s way overdue,” Bond said. “Despite the controversies that embroil this profession, these men and women get up every day and they put their lives on the line. Officer Mundy paid the ultimate price and we don’t want his name to be forgotten.”

Credit: WSBTV Videos

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured