Between the two of them, Johnny Manuel and Givonti Youngblood have spent nearly 20 years in foster care.

If that weren’t bad enough, the two of them will have no other choice but to start out anew soon on their own. Totally. The moment they turn 18, children in foster care can either sign themselves out or remain. Once they turn 21, though, their only option is to leave.

Short of losing a parent, I can’t think of anything worse than turning 21 and finding yourself completely alone.

For most of us, the transition to adulthood is a gradual process. Not only do we still get to enjoy the emotional support of parents and other family members, we can count on their financial backing as well and well past the age of 18.

»RELATED: Marietta to spend millions more redeveloping area around soccer fields

For foster kids like Johnny and Givonti, though, life is far different. They are expected to make it on their own long before the vast majority of their peers and long before they are prepared to live as independent adults.

That’s a huge problem, according to Robert Willis, executive director of the Atlanta Children’s Foundation, a local nonprofit that works to provide stability to children who have been abused, abandoned and neglected.

For Youngblood, who will turn 21 soon, and Manuel, who will soon be 20, that has meant the difference between having someone to lean on and being completely alone.

Givonti was placed in foster care in 2012 when his uncle and legal guardian since age 3 suddenly died of a stroke.

With no one to turn to, he was ushered into a group home before moving into the Methodist Children’s Home in Decatur, where he has spent the past three years.

It all ends soon. Givonti’s 21st birthday is Jan. 13. He can remain at the children’s home until the last day of the month.

His father, who was recently released from prison and whom he’s met only once, has promised to let him move in until he can get his footing.

“He’s giving me six months to a year, which I think is all I need,” Givonti said, casting his eyes downward.

Johnny, 19, said he will remain at the children's home until his 21st birthday, too, but after that, he has no idea where he'll live. But he has plans. He recently landed an internship with YearUp and hopes to attend college.

It’s a life most of us can’t even imagine, but when children can’t be reunited with their parents or another family member, this is what happens. Uncertainty.

Many will simply “age out” of the system when they turn 21, without a family and without the skills to make it on their own.

Nationally, more than 20,000 young people — whom states failed to reunite with their families or place in permanent homes — aged out of foster care last year, simply because they were too old to remain.

In 2015, of the 428,000 children in foster care, more than 17,000 had case goals of emancipation, or aging out after leaving foster care without a permanent family.

»RELATED: Flashback Fotos: School in Georgia through the years

Willis said that kids like Johnny and Givonti who age out of foster care are less likely than youths in the general population to graduate from high school and are less likely to attend or graduate from college. By age 26, approximately 80 percent of those who aged out of foster care earned at least a high school diploma or GED compared to 94 percent in the general population.

By age 26, 4 percent of youths who aged out of foster care had earned a four-year college degree, while 36 percent of youths in the general population had done so.

Willis’ foundation serves about 300 youths each year, most of them African-American males who generally come into the system older and so are less likely to be adopted.

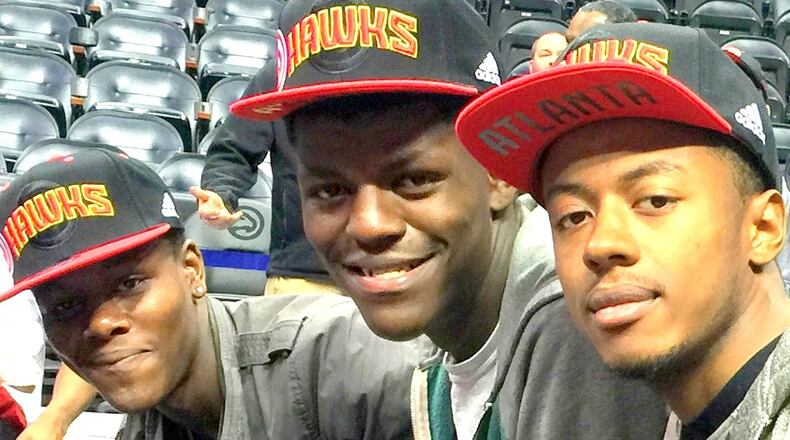

In addition to providing supportive services for children in foster care, including recreation, mentoring and a residential group home, the foundation hosts a weeklong residential camp and partners with the Atlanta Hawks to provide a basketball mentoring program. NASA and Georgia First Robotics recently sponsored a trip to the White House.

Willis said his goal now is to come up with an innovative solution to improve the outcomes for children like Johnny and Givonti who are aging out of the system. What is needed, he said, is more state support and more collaboration through public and private partnerships. For example, he recently won support from a larger financial institution to provide crisis cards to youths who have signed themselves out of care and find themselves in crisis — no food or place to live.

We need more of that. Children are not numbers. They are human beings hoping for a happy ending.

April is National Child Abuse Prevention Month. May is National Foster Care Month. That’s about when my inbox will be packed with pitches to do stories about these kids and their needs as if those two months are the only times they exist.

Of course, that’s not the case. They are with us year-round, as is the need to focus on them, to provide for them. Their health, safety and welfare ought to be our top priority year-round.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured