A haunting sound fills the room at the Auburn Avenue Research Library as people randomly call out the names of 35 men and women lynched or killed in other acts of racial terrorism in Fulton County.

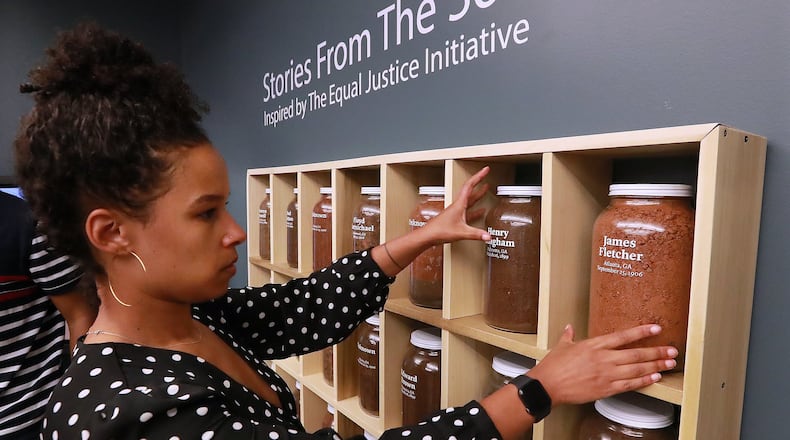

In the front of the room are rows of jars filled with rich, brown soil. Most of them have names in white lettering. A few are simply labeled "unknown."

Warren Powell.

Annie Shepard.

Thomas Finch.

Sheila Joyner-Pritchard looks straight ahead. As she says the names, she adds one.

Elijah Joyner.

Joyner was her great-grandfather who was hanged in North Carolina on Nov. 10, 1899, after he was arrested and accused of robbery and killing a store owner’s nephew. Her family denies he was guilty.

“For a moment, it took me back to a different time,” said Joyner-Pritchard, a 69-year-old semiretired social worker. “Here we are in 2019, having to remember something so dark.”

The soil was collected over several months at multiple sites as part of a project by the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition, which was spearheaded by a group of Georgia State University students.

The coalition partnered with the Montgomery, Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative to help foster reconciliation and raise awareness of racial terrorism in Fulton and throughout the South. It is also working with groups in DeKalb County, and in 2017 the EJI worked with residents in LaGrange to erect a marker to observe the lynchings of African Americans in Troup County.

“We want to change the narrative around how we talk about our history,” said Allison Bantimba, a native of Massachusetts, who initially conceived of the soil collection effort as her final master’s degree project. “We want to show the whole picture. Most of this happened in public spaces. People kept souvenirs. There were postcards. It really was terrorism and we’ve never acknowledged the severity of it and that it continues to happen in various forms.”

The collection is now part of an exhibit, “Stories From the Soil,” which is on permanent display at the Auburn Avenue Research Library, 101 Auburn Ave. NE, Atlanta.

The coalition has collected soil from Fulton's 35 documented incidents of racial lynchings and murders, including the 1906 race riots. The group hopes to get funding from EJI to erect makers.

In some cases, the exact location may not be known, so it became a symbolic gesture. Occasionally, the site now housed a business, a home or an apartment development.

Related: Ebenezer pastor: Mass incarceration is a scar on soul of America

More: DeKalb County to acknowledge lynchings through historical marker

More than 4,400 African American men, women and children were hanged, shot, drowned, burned alive or beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950 across the nation, though mostly in the South, according to the EJI.

Those are documented case. EJI officials believe that number is an undercount since it does not include people whose deaths were not reported in newspapers.

The EJI has investigated thousands of racial terror lynchings, which include hangings and mob violence, in the South, many of which were never documented.

“We felt that the history of lynching is both hugely impactful and widely unknown or underappreciated for the way it has shaped American race relations, criminal justice and — by fueling the great migration of black people out of the South in the early 20th century — geographic diversity,” said Jennifer Taylor, a senior attorney at EJI.

The incidents were so traumatic for families that they often became deeply buried secrets, said Bantimba.

Perhaps it was fear. Perhaps it just became too horrible and painful to think about. For generations, relatives tucked those memories in a deep place, rarely talked about. Some families fled to safer communities or states.

Related: Pushing America to race its racist past

When possible, the coalition reached out to families of the victims.

The soil collection ceremonies also became community-healing events. People would come up and participate in the ceremonies. The coalition grew to include students and professors at other universities, activists and artists. They leave flowers at each site.

Bantimba initially kept the jars in her home, where she found herself becoming very protective of them.

“No one took care of these persons during their deaths,” she said. “I wanted to make sure they were in a safe space.”

The violence spared no gender or age.

For instance, Warren Powell was 14 when he was killed by a mob in East Point in the summer of 1889 for “frightening a white girl.”

Annie Shepard was shot in the chest at point-blank range as she walked home from work on Sept. 22, 1906, during the Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the Atlanta Race Riots.

Thomas Finch was a 27-year-old hospital orderly, who was killed on Sept. 12, 1936, by white police officers, who took him from his home in front of his family in the early morning hours.

On a recent morning, Joyce Finch-Morris watched as members of the coalition collected soil at her home before going to a ceremony.

Her great-uncle allegedly raped a white woman, but the family never believed the claim and said the two knew each other.

Police said Thomas Finch resisted arrest. All his family knows is that he was shot and killed.

“This made it real,” said Finch-Morris. “It was almost as if I was attending his funeral.”

In a March 2012 TED Talk, Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the EJI, said many people don’t know about the racial terror unleashed on African Americans that began at the end of Reconstruction and went on until the end of World War II.

For many African Americans in the United States, he said, it was an “era defined by terror. In many communities, people had to worry about being lynched. They had to worry about being bombed. It was the threat of terror that shaped their lives.”

Terror in this country did not begin after the 9/11 attacks, he said. For blacks, it started much earlier. People come up to him and ask him to tell people “that we grew up with that.”

In an unrelated project, in 2018, the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center for Racial Healing erected a plaque listing the names of roughly 600 men and women who were lynched in Georgia. Most of those killings were done without people getting due process from the judicial system, said Executive Director Catherine Meeks.

“People want to talk about slavery or mass incarceration or the death penalty without talking about lynching,” she said. “You have to realize that it is all part of the same fabric. You don’t get to just pick one. You have to look at the whole thing. Police killings of today are just another way to lynch people, and those killings are expressions of the same type of hate-filled energy that made it possible for the earlier lynchings to take place.”

Not all lynchings were spontaneous, she said. Some were planned and advertised. “People would leave church and go participate in a lynching. People would get their kids and take a picnic basket. It’s absolutely horrifying to think how much lynching was considered a normal thing.”

The Rev. Elliott Robinson took his 13-year-old daughter, Patricia, to gather soil in Palmetto.

At first, he was driven by curiosity.

“Then as the process began, it started to feel very solemn and sacred,” he said. “It got real when you put your hands in the soil. You could almost feel their blood in the soil, and that created a connection. It was much deeper than me or my daughter expected.”

He was struck by the care people took to make sure there were no sticks or rocks in the soil. One woman broke down in tears.

Most importantly, though, Robinson hopes the spirits of those who died realize they are not forgotten.

EXHIBIT PREVIEW

“Stories From the Soil”

Auburn Avenue Research Library, 101 Auburn Ave. NE, Atlanta. 404-613-4001, afpls.org/auburn-avenue-research-library.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured