Parents race against time to try and save their son Easton

Easton Walker is a 17-month-old charmer. With a flop of red hair and pale blue eyes, the toddler smiles at just about everyone he meets.

But behind the playful smile is a debilitating disease. A feeding tube, as well as a port catheter (or port for short), for weekly infusions, are hidden underneath Easton’s sky blue T-shirt.

This little boy in Lawrenceville has Hunter syndrome, a rare genetic disease with only about 500 cases in the United States and 2,000 around the world. There is no cure for this disease, which causes the progressive loss of physical and mental function. Children with Hunter syndrome gradually lose the ability to walk, talk, even eat.

But there are glimmers of hope with groundbreaking research and potentially life-saving gene therapy clinical trials which may extend lives, and perhaps even lead to a cure.

Easton’s parents, Rebecca and Scott Walker, are on a mission to try and help save Easton and other children suffering from Hunter syndrome. But they are racing against time. Most people with Hunter syndrome don’t survive past their teen years.

“I tried to prepare myself, but no parent can prepare themselves for someone to tell you your child is going to die if no cure is found,” said Rebecca Walker. “I will research and advocate, and do the best I can to help him… I want him to know what it’s like to live.”

A normal pregnancy

Rebecca Walker, a mom at 24 years old, had a seemingly normal pregnancy. There was nothing unusual than turned up during ultrasounds.

And even though Easton was born four weeks early when he arrived on Jan. 6, 2017, he initially appeared to be just fine. He weighed a healthy 7 pounds, 12 ounces. Soft, red hair on his head framed his face.

But within 10 minutes of being born, Easton struggled to breathe and started turning blue. He was rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit. His oxygen levels were low. He was diagnosed with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). Easton remained hospitalized, and after four weeks, he recovered from PPH and finally went home.

But his breathing troubles continued. He sounded raspy, congested. He struggled to swallow milk. He was constantly sick with respiratory infections. And he had a large lump on his back. At first, doctors dismissed the string of health woes as nothing serious. But Rebecca knew something was not right. She carried her baby from one specialist to another for months until last November when a specialist identified the probable cause of Easton’s complex health challenges with a simple urine screening test for Hunter syndrome. A genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis.

“As a mother, I knew something was wrong,” said Rebecca on a recent morning at home. “But did I think my son was dying? Definitely not. I am heartbroken for him.”

After the diagnosis, Rebecca feverishly researched online for resources for the disease primarily affecting boys. She connected with other families banding together to give each other support, but also to raise awareness about the disease, and raise money to help fund crucial research and clinical trials.

Hunter syndrome is one type of a group of inherited metabolic disorders called mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs), and Hunter syndrome is referred to as MPS II.

Since it is a recessive, X chromosome-linked disorder, boys inherit the malfunctioning gene only from their mother. Rarely is the disease observed in girls.

Children with Hunter syndrome lack a particular enzyme that breaks down and flushes out complex sugar molecules in the body. Without this enzyme, massive amounts of these complex sugar molecules collect in the cells, blood and connective tissues, causing permanent and progressive damage especially in heart valves, airways and the brain.

The symptoms of Hunter syndrome are generally not apparent at birth. Physical appearances of many children with Hunter syndrome include stunted growth and distinct facial features — a prominent forehead, a nose with a flattened bridge and an enlarged tongue.

Living with Hunter Syndrome, fighting for a cure

Stuffed animals and toys fill a room at the Walker home in Gwinnett County. Mickey Mouse plays on the television. Crawling on a beige carpet with a ball in one hand, Easton giggles, a smile stretches across his face.

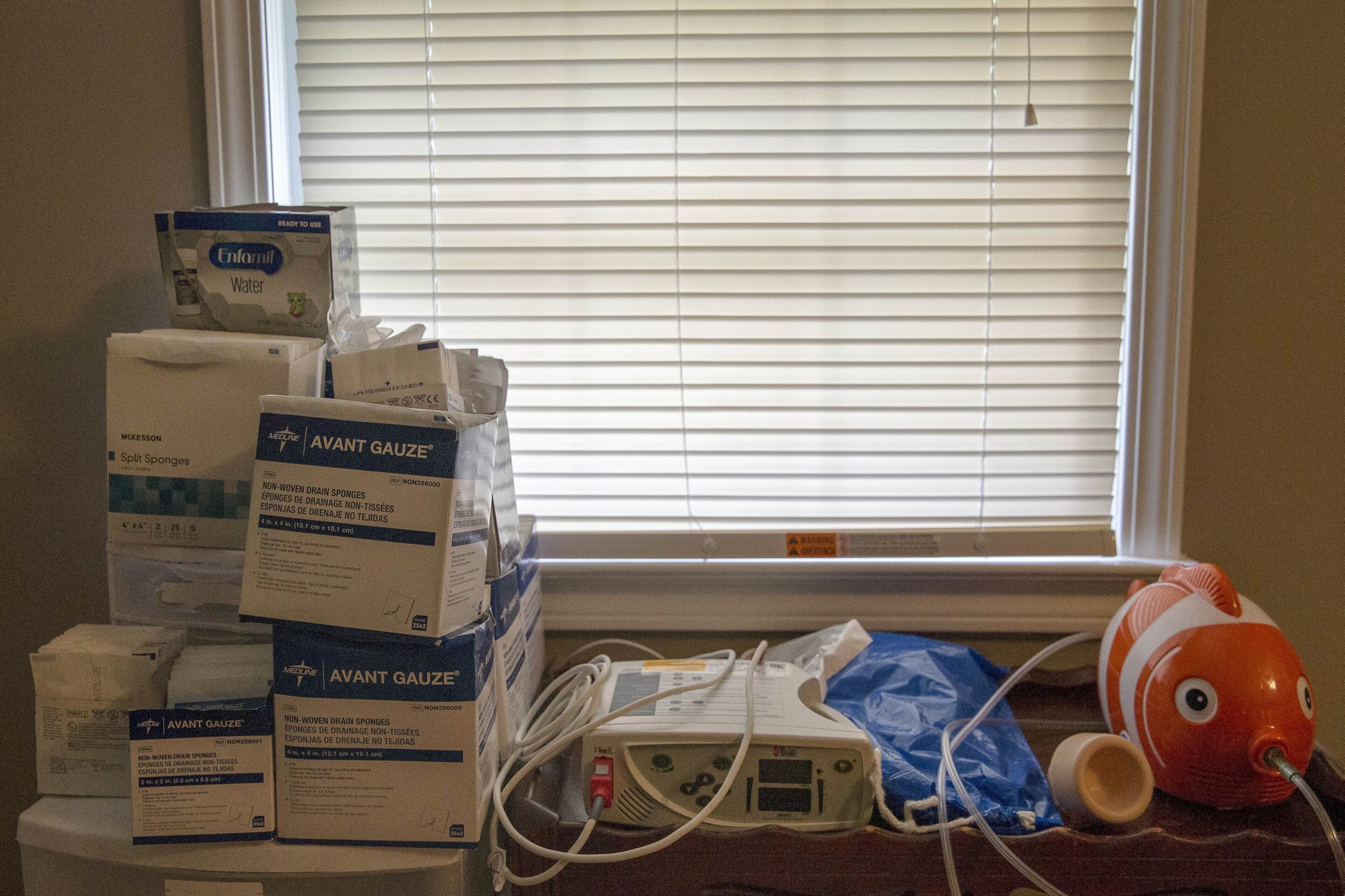

It’s a happy moment, but there’s no escaping the reality of life with a medically fragile child here.

Easton has two breathing treatments every day. He has in-home therapies almost every day for various therapies — physical, speech, occupational therapy.

And once a week, Easton undergoes a five-hour-long enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) infusion at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) uses an intravenous solution (IV) to replace the deficient or missing enzyme in the body. ERT can slow the progression of the disease by increasing the amount of missing enzyme in the body.

Dr. William Wilcox, a medical geneticist and professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, and who is one of Easton's doctors, said weekly enzyme replacement treatments can prevent damage to heart valves and help those with Hunter syndrome breathe easier. It can also help ease stiff joints and make it easier to move around. But the benefits are also limited. The enzyme replacement infusions only last about a day or two, requiring on-going weekly treatments to try and stall the progression of the disease. And the injections don't cross the blood-brain barrier, which means that they can't prevent or reverse any brain damage.

Wilcox and other researchers have been working on creating a new enzyme replacement treatment which would reach the brain. Wilcox and his team recently completed a clinical trial with the newly developed drug, and are awaiting results.

Jeanette Henriquez, president of the Hunter Syndrome Foundation, and parent to an 8-year-old son, Dominic, with Hunter Syndrome, said she's encouraged by emerging research, but desperately wants more treatment options available for children with Hunter Syndrome as soon as possible.

“We as parents have a sense of urgency,” said Henriquez. “It is really important to get this moving. These are our children, and we have a time limit on their lives.”

Henriquez said her son Dominic has been participating in a clinical trial in Chicago (a different one from the one led by Wilcox), which administers enzyme replacement injected directly into spinal fluid so it could easily reach the brain. She and her son make monthly trips to Chicago for the treatment. She is confident it’s helping stabilize the disease.

But the enzyme treatments are only treatment and not a cure. For Henriquez and other parents, they are placing their hopes on cutting-edge gene therapy, still in its early phases.

Last November, scientists used gene-editing tools on a human for the first time when an adult patient named Brian Madeux, who likely has the milder version of the disease, underwent a medical procedure meant to cure his Hunter syndrome. More safety information and early results on effectiveness should come during the coming months.

Gene therapy replaces a faulty gene or adds a new gene to cure disease or improve a body’s ability to fight disease. Gene therapy holds promise for treating a wide range of diseases including cancer, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, and AIDS, and now Hunter syndrome.

Shortly after Easton's diagnosis, Rebecca connected with Project Alive, a non-profit started four years by a small group of moms with children with Hunter syndrome. The organization, dedicated to raising funding for clinical trials they hope will lead to a cure, has produced a multi-episode docu-series.

The parent-led organization has also raised close to $1.8 million. Donations included $1 bills from young children contributing their allowance to the cause as well as several family-led fundraisers. Mark Cuban, entrepreneur and Dallas Mavericks owner, donated $250,000. The organization is nearing its goal of raising $2.5 million to help fund a gene therapy trial at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

“My heart is with the families,” said Melissa Hogan, one of the founders of Project Alive. “That first year is so horrible, and so lonely. When my son was diagnosed, there were no trials, no options. I just knew he was going to disappear in front of me and die… My message to Rebecca is there is hope. There are options now, and there are more options coming down the pike.”

‘Making the most of the unfortunate life’

On a recent morning, Easton smiles at the television before taking a little nap. When he wakes up, Rebecca places him in his high chair and gets everything ready for the feeding tube. She connects the tip on the end of pump set into the feeding tube. She sets the flow rate on the pump. Easton holds onto a Mickey Mouse stuffed animals and wriggles a little before settles down, seeming to accept the way he gets most of his nourishment every day.

Rebecca, who had planned a career as a pediatric nurse, is now a full-time, around the clock caregiver for Easton. She has several binders with information about the disease. She also posts updates and stories about Easton on a special Facebook page.

Scott works as a full-time truck driver. The Walker family had been living in the Winston-Salem area but recently relocated to Georgia to be closer to family.

Rebecca and Scott, who met on a blind date in 2014 and have been together ever since, said they try to take Easton’s condition one day at a time. They both credit Easton’s cheerful disposition with giving them strength and comfort.

“We are trying to make the most of the unfortunate life we’ve been given.”

He is beginning to stand and showing signs of taking his first steps. He mostly babbles but clearly says “Mama,” “Dada,” and calls his grandmother “Mimi.”

They try to go outside every day to play in the yard and plan fun day outings. They are planning a trip to the Georgia Aquarium one day soon.

“I have to try focus on the present and him, and living,” she said.

When Rebecca was pregnant, she sang “You are my Sunshine” to Easton every day.

You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray.

She still sings the song to Easton. But it hurts every time, she sings “please don’t take my sunshine away.”

MORE: The Atlanta Braves are making games way more accessible for fans with autism