OPINION: Has cursive writing outlived its usefulness? Maybe

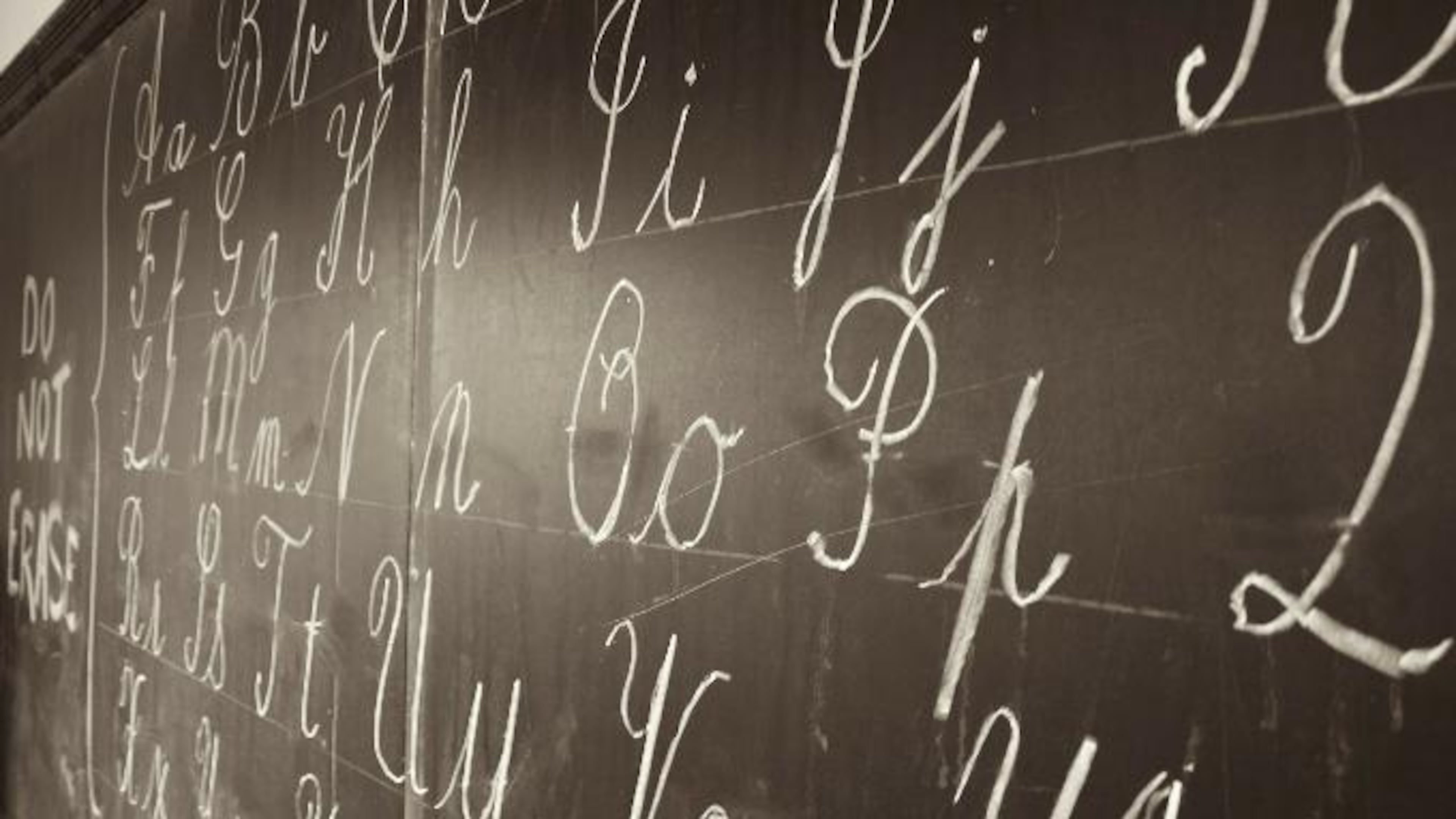

The year my daughter was born, cursive was axed from the national Common Core standards for K-12 education.

For those of us in older generations, writing and reading cursive was a basic skill taught by schools. But, in this digital age, it’s a lost skill, a relic of the past.

Earlier this month, when my daughter had to sign forms for a field trip, she struggled to remember how to write her name in cursive.

Relying on a few long-forgotten, self-taught lessons, she practiced on a sheet of notebook paper before settling on a signature. I watched her efforts and felt guilty that I hadn’t continued to reinforce this skill.

Society evolves and learning must evolve with it. But, when one of the most progressive states in the country takes a leap into the past, it’s worth it to at least consider the reasons why.

Last Friday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom made headlines for signing a bill that requires the teaching of “cursive or joined italics” for grades one through six. One of the stated reasons? Because many historical documents are written in cursive. California officials could imagine a future world in which the Declaration of Independence would have to be translated for U.S. citizens.

The Georgia Department of Education recommends cursive writing instruction in third and fourth grades. But the skill is not part of state level assessments, and that makes it less of a priority, so I imagine many students across Georgia struggle to loop together a bunch of squiggles whenever they attempt to communicate in cursive.

Prior to the 1930s, schools exclusively taught cursive to students. Then schools began to teach block letters in the primary years as a transition to cursive. That continued until the 1980s, when typing began appearing as a requisite in schools. This paved the way for text produced by word processors, computers and other keyboards — and rendered cursive unnecessary.

There are some timeworn arguments for retaining cursive, even as keyboarding assumes a larger role in our daily lives. Sure, there’s the problem of students not being able to read the Declaration of Independence, as well as anything else – letters, journals, official documents — written before the 1930s.

And we don’t even have to limit the discussion to historical documents. There are present-day moments that someone not versed in the art of penmanship could miss out on, like thank you notes and birthday cards and other communications that often come only from those who are older.

Recently, my daughter’s school invited grandparents (and other special friends) to the campus for the day. Those visitors had the opportunity to write letters to their students.

During one mid-morning letter writing session, a grandmother wondered out loud if she should write her missive in cursive. She posed it as a question but quickly answered it herself. Her grandchild would not be able to read the letter if she used cursive, she concluded. She wrote in print.

There are some advantages to writing in longhand. I know that when I take notes by hand during interviews, I have a much better recall of the words I have written and can easily remember the important statements made by the interviewee. I generally write in cursive because it is faster than writing in print. Sometimes, I can’t read what I’ve written, but that’s not because I wasn’t well trained in cursive. It’s just hard to capture 150 words a minute (the average number of words spoken per minute in a normal conversation).

If none of these current efforts to revive penmanship instruction in schools translates into proficient cursive writers (and it hasn’t so far), we will be moving toward a future in which only a select few know how to read and write in cursive.

Regular readers of my columns know I’m usually all in favor of preserving those things that give us a better understanding of history and, therefore, a better understanding of now. But strangely, I don’t feel that strongly about cursive.

No doubt it’s useful when reading original documents. Some studies show learning it — and using it — helps in retaining knowledge, aids in brain development and improves motor skills.

And I’ll probably strongly nudge my daughter to practice it again.

But more important to me is that she and her peers learn to communicate clearly, whether that’s in block lettering or cursive.

Read more on the Real Life blog (www.ajc.com/opinion/real-life-blog/) and find Nedra on Facebook (www.facebook.com/AJCRealLifeColumn) and Twitter (@nrhoneajc) or email her at nedra.rhone@ajc.com.