Horizon Theatre marks World AIDS Day with new play, “Love, M.”

With all the HIV drug treatment commercials these days featuring happy, engaged, otherwise healthy people, it’s hard to remember a time when the disease wasn’t depicted as a manageable chronic illness.

In 30-second television spots, people walk their dogs, paddle canoes or go on romantic dates with loving partners. This is the hopeful, and for many, true face of HIV in 2021. With the help of a pill, life goes on, and there is a long, hearty future to plan for.

The dark days, when couples tearfully danced in clubs to Janet Jackson’s AIDS tribute, “Together Again,” are part of a seemingly distant past. So, too, are the early, hopeless days when a diagnosis surely meant a premature death.

As those difficult moments pass, so too do the mothers and fathers whose sons died in the initial years of the AIDS epidemic. About 10 years ago, playwright Clarinda Ross began interviewing some of those parents. Throughout her stage and television career, she’d lost friends to the disease, but for each death there was the story of a parent who’d buried a child.

“I thought, ‘Who am I to write an AIDS play?’” said Ross. “Tony Kushner had already done it. Larry Kramer had already done it. But I can write from the perspective of the mothers.”

On Dec. 1, World AIDS Day, Ross’s play, “Love, M.” has its virtual premiere at 7 p.m. through the Horizon Theatre Company. Directed by Heidi McKerley, the show runs on-demand through Dec. 31 and was co-produced by the Black Leadership AIDS Crisis Coalition and AIDS Healthcare Foundation. It tells the story of two mothers and two sons in the early days of the devastation. Lamman Rucker, a star of the OWN network show “Greenleaf” and Broadway veteran Terry Burrell, portray one son/mother pair. Ross and actor Chris Hecke portray the other.

Told primarily through a series of letters and voicemails (remember those?), it is a reminder of how the closet trapped not just sons but entire families in fear at the dawn of the AIDS crisis. There were often tremendous social consequences to coming out as gay, and the specter of a then untreatable disease made that choice even more difficult. Even if a family remained quiet, they were often ensconced in a culture that portrayed being gay as wrong or deviant.

“For the mothers, their neighbors, their churches, their friends were telling them their sons were bad,” Ross said.

Those parents are in their 80s and older now. Ross, who began her early career at the Alliance Theatre, spoke with about 30 parents, siblings and close relatives of men from around the country who had succumbed to the disease. She also interviewed 20 sons who lived through the era, as well as one of the early founders of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, Gert McMullin.

Claudia Lukes, of Redondo Beach, California, was the first mother Ross interviewed. Ross said Lukes’ candor “lit a fire in me to push forward with this project,” when Ross was unsure where she could do it. The encouragement would prove necessary for the obstacles ahead.

What struck Ross was that even though decades had passed, many parents were still reticent about speaking about their sons. They often requested anonymity. More than half of the families said they still worried what fellow church members or friends might say if the true nature of their sons’ illnesses were somehow revealed.

Then, there were the sons who freely spoke with Ross about being gay and living through the worst of the crisis, until asked if their mothers were willing to be interviewed.

“I’d talk to all these successful guys, and I’d say, ‘Can I talk to your mommy?’ and they’d say, ‘Oh, no! Mommy doesn’t talk about it. She knows I’m gay. She knows he’s not my roommate, but we don’t talk about it,’” Ross said. “Shame was and is such a big deal.”

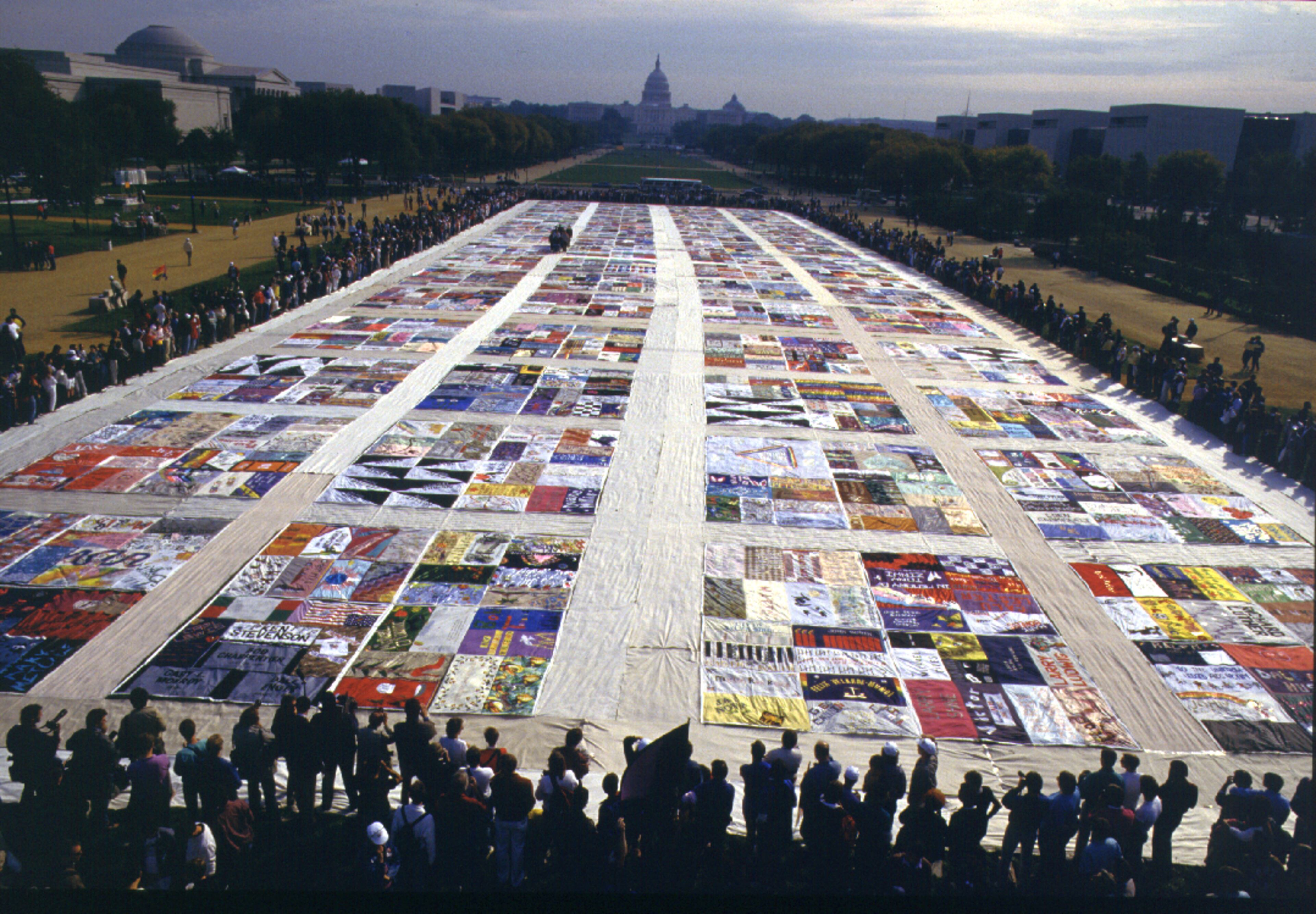

It’s an emotion Gert McMullin encountered unceasingly in the mid-1980s as the AIDS Memorial Quilt was in its infancy in San Francisco. At the time, at just under 2,000 panels, the quilt would grow to become the largest folk art project in the nation’s history. It now has more than 48,000 panels representing lives lost to the disease.

One of the characters in the play is based on McMullin and bears her name — Gert. She moved to Atlanta when the administration of the quilt under the NAMES Project, moved to the city in 2000, because of the disproportionate impact of the disease on Black people. The project recently returned to San Francisco. The Gert character is friends with the son, Chris, portrayed by Hecke. Chris is from Atlanta but living and coming out in San Francisco. He corresponds with his mother, Deborah, who still lives in Buckhead. But the relationship quickly becomes fraught.

McMullin said the Chris character is inspired by a real-life, early member of the quilt project who was from Georgia. After the man came out to his parents, they disowned him in a letter, McMullin said.

“He gave me the letter, and it was really odd when he gave it to me,” McMullin said. “I put it with all the other letters I had. His family didn’t want to talk about him being gay.”

Themes of faith and shame are strong threads in the play, particularly between the characters Timothy and his mother Myrtle. They are Black and from rural North Carolina, though the Timothy character has moved to Atlanta is working for the Carter Center. He is out. Myrtle is a deeply religious woman who constantly quotes Bible verses to her son and wants him to repent what she views as the “sin” of being gay.

Burrell, who portrays, Myrtle, remembers the first friend of hers who developed AIDS. He was a makeup artist and hairstylist for a cabaret show, and Burrell performed with her sister, Debye, in New York City in the early 1980s.

“He had this unexplainable fever, and he’d go to the hospital, but they couldn’t figure out what was wrong,” Burrell said. “He would sign himself out of the hospital and come do our hair and makeup then sign himself back in after he did our shows.”

Burrell said he battled for about five years before he passed away. The memory still feels fresh.

“The play feels so present with me because he was the person I had the most contact with,” Burrell said. “I was there in his hospital room. I would crawl into his bed, and we’d hug and talk nonsense and tell stories.”

After his death, Burrell found herself attending many memorial services.

“I went to memorial services, and I realized I kind of knew about their lives but not all the details,” Burrell said. “Through brothers and sisters, cousins, classmates telling these stories, they became three-dimensional. You came to know who they fully were.”

“Love, M.” makes the plea not to wait until it’s too late to get to know the truth of a person’s life and to show them acceptance.

“If you are a conscious human being, these things challenge you to be kind,” Burrell said.

VIRTUAL THEATER EVENT

“Love, M.”

7 p.m., Dec. 1, horizontheatre.com/love-m

Viewers can attend a post-show community conversation following the premiere. The event is in partnership with rolling out Health IQfeaturing actor Lamman Rucker; Daniel Black, professor of African American Studies at Clark Atlanta University; psychologist Shalonda Crawford; and Daniel Driffin, HIV/AIDS activist and co-founder of THRIVE SS and chair emeritus of The Young Black Gay Men’s Leadership Initiative (YBGLI).