COVID turned nursing home social worker into lifeline for residents, kin

She never imagined it would last so long. Then again, who did? When Sandi Thurber closed the nursing home doors in early March 2020 amid the coronavirus pandemic, she told herself they would only be shut a couple of weeks. Now, a year later and the doors reopened, tears soak the blue medical mask on her face when she stills herself to reflect on all that has happened, all that’s been lost. Thurber prefers to keep moving, to stay focused on the beloved elderly residents who need her. This year has proven she needs them just as much.

‘This is my calling’

Every morning during her drive to work, Thurber prays.

“I ask the Lord to use me to help others,” she said. “And when I arrive, there they are, our residents, waiting for me. They’re why I’m here. This is my calling.”

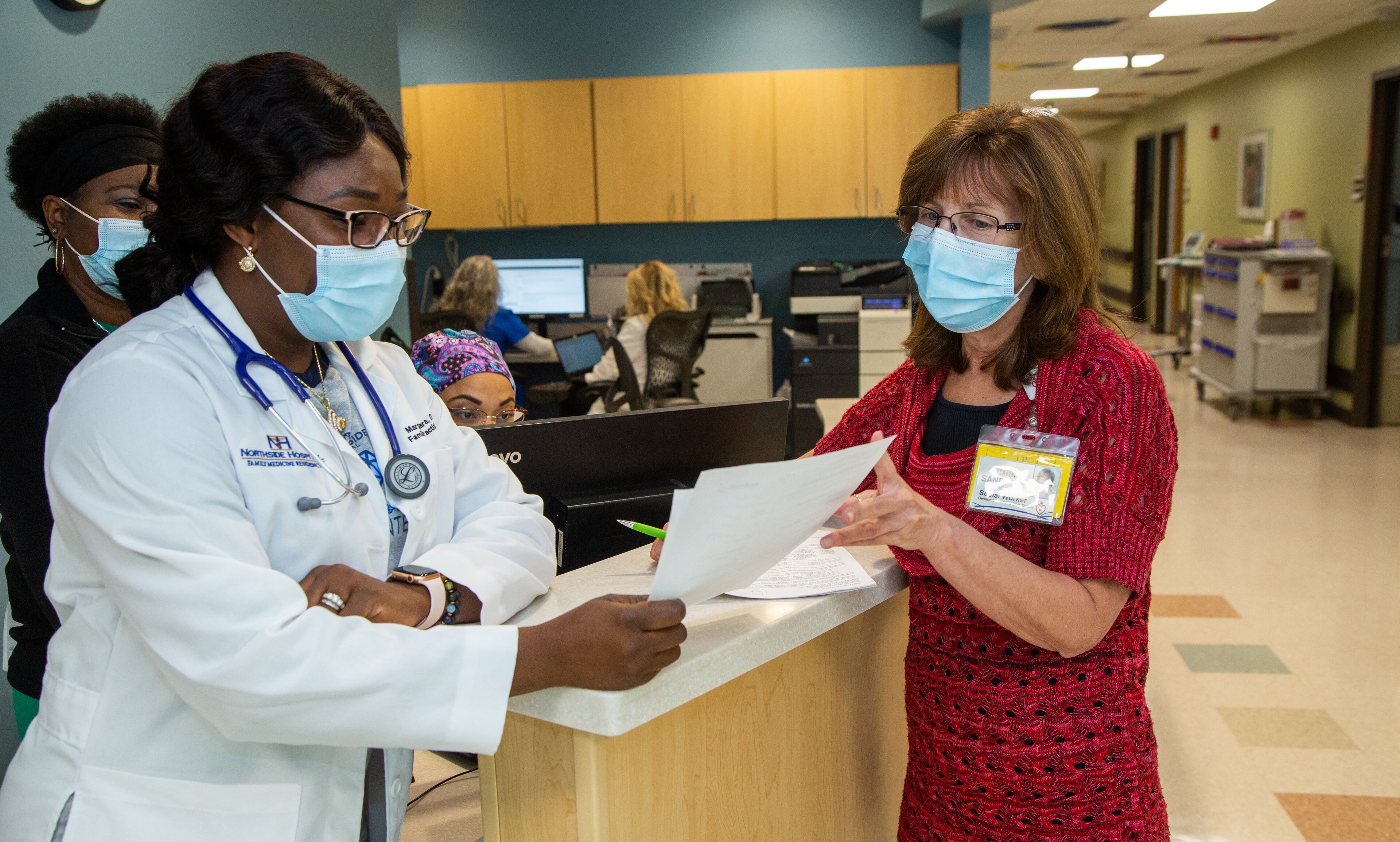

Thurber, 61, has spent her entire professional career in nursing homes. As the social service director at Northside Gwinnett Extended Care Center for the past 15 years, she is the front-line employee for residents and their families. If there is an issue to resolve, a question to answer, it is Thurber they turn to. She had always considered her job busy and engaging — then a worldwide pandemic hit, redefining “busy and engaging.”

“Over the years, we have had other illnesses, like the flu or a stomach bug, go through and we’ve limited visitation, so we figured we were in for something similar,” Thurber said. “But then the call came from administration, telling us we had to close our doors immediately and get the families out. Nothing like that had ever happened. We had to go room to room and ask families to gather their things and say goodbye to their loved ones. We escorted them out and locked the doors. It was awful, so, so awful.”

Though NGECC temporarily stopped accepting rehabilitation patients, they were still caring for many at the beginning of the pandemic. Rehab patients are usually sent over from hospitals and typically stay for limited stints to regain strength and skills before returning to their homes. Because they were not as established as the long-term residents, not as familiar with the staff, these individuals and their families struggled greatly with quarantine protocol.

“One lady in particular would come knocking at the door,” said Thurber. “Her husband was in rehab and had dementia. She’d beg me to let her in, telling me they had never been apart, and their hearts were breaking from the separation. She came multiple times. One day she cried ‘you don’t know what it’s like.’ I couldn’t help myself from crying when I told her that yes, I did know what it was like. I had not seen my family either. The woman apologized, said she would be patient, and asked that I please do my best to get her husband home to her.”

Thurber’s small frame shudders, her head shakes side to side as she recalls a handful of disgruntled people who never considered what quarantine must have been like for the NGECC employees. They were struggling, too. And they were sacrificing time with their families to care for others’ loved ones.

Sacrifices made to stay healthy

Thurber is the mother of two girls, Megan and Amy, and the grandmother of a hazel-eyed brunette named Evelyn, age 3, a girl who affectionately refers to Thurber as Didi.

Megan Wiggley, Thurber’s older daughter, describes Thurber as the consummate mother. Always the room mom and team mom, she’s selfless, talkative, she loves to spoil others and lift their spirits. She always does the right thing and, Wiggley said, her mother shines in chaotic moments. She is the calm in a storm, a beacon of strength for her family.

“That stretch from the beginning of quarantine until summer is the longest we’ve ever gone without seeing each other,” said Wiggley.

When Evelyn turned 2 in March 2020, the family had a big birthday planned, but soon realized they couldn’t get together.

”We went from seeing each other often, to settling for FaceTime calls, and birthday gifts and Easter baskets sent through the mail. Mom could not take any risks and, though it was awful, we understood. She was protecting herself so that she could continue protecting and serving the vulnerable people at work. They depend on her and she takes her responsibility to them seriously.”

The stress of staying healthy overwhelmed Thurber.

“I was so scared of getting COVID,” she said. “I didn’t want it for me or my family, and I didn’t want to be forced away from work for two weeks, unable to check on my residents. I love my time with them. God put me here to take care of them and I give this job all I have. ... So, for the majority of the past year, I have had limited contact with my family, no get-togethers with friends, no restaurants, no church. It was work and home.”

Thurber resides alone in a ranch-style house in Grayson. It’s a cozy refuge, decorated in blues and pale turquoise, colors that soothe Thurber. She loves her back patio, where she often sits after work, decompressing as she watches birds flitter around the feeder in her backyard, tucked in by wild green growth. For years, she would head to the park after work to run a few miles, but that habit ended when quarantine began. She no longer had the energy. Her new routine is simple and quiet, punctuated by a 6:30 p.m. FaceTime call each evening with Evelyn. Thurber’s voice breaks as she describes those calls, her sweet granddaughter’s face on the screen, where they read, sing and giggle together.

“I need that daily connection to my family so desperately,” said Thurber. “Even if for just a minute, it means so much. My daughter Amy will call on her drives home from work, too. We catch up, we share, we support each other. We need that.”

In June 2020, Thurber finally reunited with her family face-to-face. Little Evelyn may have been more excited than anyone.

“Evelyn always watches for her out the window,” said Wiggley. “That day, when she saw mom’s car coming, she ran out to the driveway to greet her. ... I’d felt so bad for Evelyn because everyone just disappeared one day. She loves her Didi, she’s probably her favorite, and she had disappeared the longest. Happy as I was to see mom, I was even happier to see her holding my little girl again.”

‘Just like family’

As the number of positive COVID cases declined, the rehab patients at NGECC were sent home and, for months, 100% of the facility’s focus shifted to the long-term care residents.

“We concentrated on keeping the residents at their highest level of emotional, spiritual and psychological health,” said Thurber. “We cleared out bushes and replaced them with chairs and benches to better facilitate window visits. We quickly learned that a window is great, but more than half of the residents do not have cellphones. My personal phone has now been used by just about every patient. It enhances visits so much when they can talk and see one another.”

For many, the past year marked their first holidays celebrated without family. The staff made great effort to keep morale high. They dressed in costumes and paraded down the halls for Halloween. At Christmastime, they caroled from room to room with a boombox, and Santa Claus made a surprise visit at the big window by the day room. Thurber worked every holiday. She took pictures of the residents enjoying Thanksgiving lunch, and pictures of their smiling faces topped with Santa hats. She shared the photos with the residents’ loved ones. It was the best gift she could offer.

The residents struggled to understand why their families could not come inside, why they had to wear masks all day, why their activities ceased, and why they no longer ate together in the dining room.

“It was all so heavy,” Thurber said. “Some residents got mad and thought we were mean to keep them from their families. Some would sit at the window and cry. Sometimes we’d sit and cry with them.”

Before the pandemic, nothing kept Tony Perrigan from visiting his mother, Cledith Perrigan. He moved her to Georgia from their native Tennessee years ago so he could oversee her care. Cledith Perrigan raised him as a single mom, and, according to him, anything good that can be said of him is a credit to her. Cledith Perrigan is 92 and has been a resident of NGECC for nearly four years. Wheelchair bound, she suffers from COPD, diabetes and congestive heart failure. She has defied a couple of close calls and, though her health has continuously declined, she is a joyful person, a big hugger, often dressed in her favorite hues of purple or red. Tony Perrigan, who shares the same brilliant blue eyes as his mom, has had great concern about her isolation over the past year.

“I was accustomed to visiting her every other day, sometimes more,” he said. “I’d take her out to the garden, and we’d sit and talk. She participated in activities and had her best friend Miss Ann next door, but Miss Ann passed right before the pandemic began. Then all activities came to a stop and I couldn’t visit her. She needed to see us, and it hurt her health greatly when she couldn’t.”

Tony Perrigan knew NGECC made the right move by closing the doors to visitors, but he never expected a year to pass before he could wrap his arms around his mother again. He stayed in continuous communication with Thurber and expressed his frustration to her more than once.

The facility restarted outdoor visits last summer, but just six weeks into those visits, a staff member tested positive for COVID-19 and visitations stopped, Thurber said.

“That was one of my absolute worst days. I cried during my calls to families, devastated to disappoint them after they’d finally been able to reconnect. We were back inside, doors locked,” she said.

Tony Perrigan has always held Thurber in high regard, even more so throughout the pandemic. Her dedication and genuine care for the residents is unmatched, he said.

He recently asked Thurber to be by his side when he had to share terrible news with his mother. Her youngest brother has terminal cancer.

“I wanted Sandi there to help comfort my mom and she never hesitated. She was there, just like family,” he said.

Cathy Holcombe, whose father, John Dean, was a resident at NGECC for 12 years, can’t imagine what the past year would have been like without Thurber.

“I don’t know how Sandi balances all those patients and family members, but she’s always on top of everything,” said Holcombe. “It helped so much to know that dad was in her care, especially when I couldn’t be there.”

Before the pandemic, Holcombe would pick her father up and take him for drives around Duluth, where he spent his childhood. Dean had Alzheimer’s and struggled with the past and present. His family farm no longer exists, but he loved to go for drives to see what remains and talk of days gone by. Holcombe would take him to Walmart to shop, then they would warm a restaurant booth and share a meal before Dean had to return to NGECC. When those outings stopped last spring, Dean’s medical issues worsened. By summer, Holcombe could tell by her father’s gruff, country voice that he was weakening.

“In August, Sandi called to say his medications were not helping and they had to send him to the hospital,” said Holcombe.

Doctors informed Holcombe that her father did not have much time to live. He was placed in a hospice facility on a Monday and died that Friday.

‘These are my people’

At the height of the pandemic, NGECC transformed a secluded hallway into a COVID wing, secured with temporary walls and doors. As of May 2021, they have not used any of the four rooms on the hall for COVID patients, as none of their residents have tested positive. Employees are tested twice a week and residents are tested when positive cases arise. All employees and residents have been vaccinated.

“We have put our policies, procedures and core prevention into place to keep our staff and residents safe. To me, that is winning the war,” said Tamey Stith, the NGECC administrator. “To see we have weathered the storm this long and have healthy, safe residents — that’s been the ultimate goal and it makes me so proud of this team. Sandi’s role in keeping families updated, and bridging together staff and residents, extending everyone’s version of family — it has been remarkable.”

Tears pool in Thurber’s soft blue eyes. She removes her glasses to wipe them, her effort futile. Her chin trembles when asked about bright moments over the past year. Her hands clasped, her narrow shoulders rise and fall as she contemplates an answer.

“If not for COVID, I wouldn’t have been able to grow as close to some of the residents,” said Thurber. “My responsibilities with the rehab side paused, which gave me more opportunities for visits. There’s one particular lady who has dementia. She has no children, she’s a bit difficult, and I spent a lot of time with her, keeping her focused and positive. One day we were sitting in the garden together and she introduced me to a staffer. She said I was her daughter-in-law. When I realized she felt that close to me, like I was her family, it brought my heart such joy.”

Simple things, like popping in to watch a cooking show with a resident or shuffling down the hall to watch crime stories in the afternoon with another have been some of Thurber’s fondest memories. “It has been a lonely year for all of us; we needed each other for companionship. These are my people. It is my job to care for them and love them like family, especially in times like these. It is one of the greatest privileges of my life.”

Grateful for ordinary sights

The halls in NGECC are currently graced with a limited number of visitors most days. This comes to a halt if a positive test arises, but normalcy is tiptoeing back in, and residents, their families and the staff are grateful. Some residents are eating in the dining room; others are socializing in the day room.

Some situations in life are too traumatic to absorb, Thurber summarized when asked what toll the pandemic took. She is unsure if she has taken it in yet, if the weight of it all will ever truly land, but she believes the tide is changing and she welcomes it, palms open. She continues her nightly FaceTime calls with Evelyn and sees her and her daughters a couple of times a month. She has found the energy to start running again. The flame that illuminated her path the past year grows stronger. She calls it hope.