Bid farewell to the Southern twang.

Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow. But Georgians are high-tailing away from that grits-and-gravy drawl faster than a scalded dog.

A collaborative study between linguists at the University of Georgia and Georgia Tech tells us that the Southern accent is disappearing. Baby Boomers still sound similar to their parents. But among Gen Xers, they discovered, the accent “fell off a cliff.”

A team of 70 undergraduates and graduate students helped analyze hundreds of hours of conversation, recorded over nine decades, and uncovered this generational divide.

The recordings sampled speech from Georgians born as long ago as the late 1800s all the way up to those born in the current century. The samples included recordings from the Linguistic Atlas Project.

Only native Georgians were analyzed. Those who spent more than five years out of the state were excluded.

What they found is that the drawling vowels that typified Southern speech — even as recently as the 1970s — have vanished like the banana pudding at Sunday dinner.

Listen: How these researchers studied the Southern drawl

Above: An audio excerpt from Bo Emerson's interview with researchers Margaret Renwick and Lelia Glass. They explain that whether you speak Southern may depend on how you pronounce words like dress, trap or face.

They published their findings in the journal Language Variations and Change. Margaret Renwick, associate professor of linguistics at the University of Georgia, said it’s tricky to determine why an accent goes away, but it probably has to do with exposure to other regional voices.

Credit: Margaret Renwick

Credit: Margaret Renwick

Consequently, the effect is strongest in Atlanta, where growth and in-migration have been explosive, and transplants from the North and Midwest have proliferated. Researchers evaluated only white speakers. Renwick said linguists are currently analyzing Black speech and have seen some of the same generational dynamics, though the accent seems to disappear later.

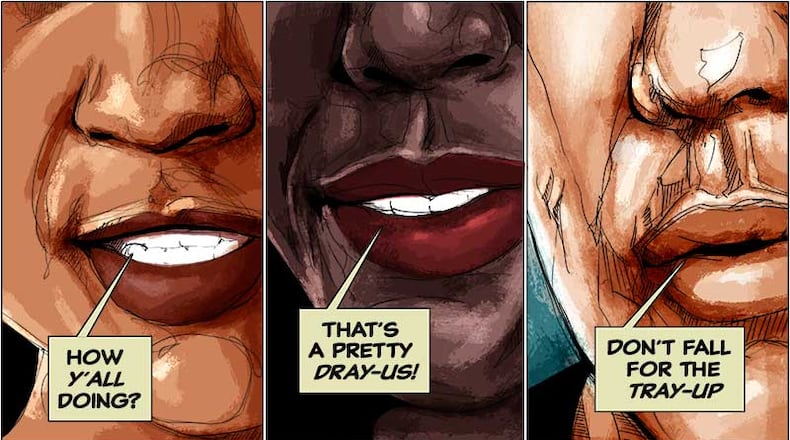

Lelia Glass, who collaborated on the study and is an assistant professor of linguistics at Georgia Tech, said one of the hallmarks of Southern speech is the “diphthongization” of certain vowels. Words of one syllable get stretched into multisyllabic sounds.

The word “dress,” for example, turns into “dray-uss.” The word “trap” becomes “tray-up.”

Renwick points out that with short vowel sounds, such as “dress” and “trap,” the extra vowel comes at the end of the word. With long vowels, such as the “a in “face,” the extra vowel comes at the beginning, so that “face” sounds more like “fuh-eece.”

This extra vowel disappears in younger speakers, said Renwick. And among Gen Z voices, the sound is shortened even further so that “dress” drops down to something like “druss” — “Not even standard pronunciation, but something you might have in California,” she said.

“It’s a pan-regional accent that has shown up in several urban areas across the U.S. and Canada,” she added.

Linguists take serious measurements when they describe an accent, and use computers to model the position of the tongue during pronunciation of key vowel sounds. Glass writes that the technique “gives us a quantitative metric of accent.”

The tongue actually drops in the new pronunciation. “If the Southern accent goes up, the new accent goes down, genuinely, like the tongue in our mouth,” said Jon Forrest, assistant professor of linguistics at UGA and a co-author.

Forrest said the new study doesn’t indicate why the accent is morphing, but earlier work might offer a clue. “Perceptual dialectology” has told us that “people have negative attitudes toward Southern accents,” he said. “They think it sounds uneducated.” Forrest has noted the same leveling of dialect in North Carolina.

Children learn pronunciation from their peers, not their parents, said Forrest. If they’re in a school with many new arrivals from outside the South, they will have many other options for accents to emulate, and they might pick one that sounds smarter.

An accent, in this way, is more like a clothing choice.

When Jimmy Carter was born, on Oct. 1, 1924, most people in the South were from the South. There were not a lot of examples to choose from. This is why Carter’s speech is non-rhotic, meaning the “r” disappears from the middle of some of his words, so that “more and more” sounds like “mo-ah and mo-ah.”

Changing demographics changed that, said Glass. “In-migration can lead to dialect leveling, where regional distinctiveness can fade away.”

Other distinctive regional accents are also dwindling, she said, including those in New York and Chicago.

Yet some folks hold onto their accents tenaciously. Gov. Brian Kemp, born at the end of the baby boom, raised in a college town, still sounds Southern. “He seems to lean into the symbolic stuff related to the South,” said Glass. “The symbols of Southernness are in his ads, the truck, the gun, the farm, the flannel shirt and the jeans. For him, his accent is, maybe, a bit like some of his clothes.”

If that sounds like performative Southernness, Glass reminds us that “we all are performing, all of the time.”

Said Renwick, “accent is aspirational for people. It’s what you want to be, what you want to put on.”

Many elements of Southern language are durable and will remain. “‘Y’all’ isn’t going anywhere any time soon,” said Renwick.

But the general trend is troubling to her. “As a linguist, I really value diversity in language,” said Renwick. “We do worry about language death. From a scientific perspective, as languages die, we lose the ability to create the full constellation of properties of human language that allows us to understand what it is about language that makes us so special.”

So if you want the next generation to know about the drawling life, get out the tape recorder, said Glass. “Everyone should record their relatives, while you can. Your grandchildren will be grateful for that.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured