Country music isn’t Marty Stuart’s only talent

Is taking a photograph like writing a country song?

The connection may seem pretty faint to most of us, but for Marty Stuart, photography and country music have always been as closely linked to each other — and to him — as family. A new exhibition at Cartersville's Booth Museum of Western Art titled "American Ballads: The Photographs of Marty Stuart" features many of the intimate images the country music star has captured throughout his storied career.

“Every time I take a good photograph it causes me to be a better musician. If I write a good song it causes me to be a better photographer,” said Stuart backstage at the Booth Museum’s auditorium before a series of opening day events, including an afternoon talk about his photos and an evening concert of his music. “I just started taking my camera on the road and photographing my life because my mom and dad and sister still lived in Mississippi. I would send them photos from the road to show them: This is who I met and this is where we went.”

As the photographs clearly show, Stuart’s road has led to some pretty remarkable people and places.

Stuart grew up in the small town of Philadelphia, Miss. The most influential photographer in his early years was his own mother, Hilda, who he says was always taking pictures of everyday family life.

“Mama could be frying chicken and then take a picture with any kind of camera, and you had an all-time family classic,” he says. “She just knew when to pick up the camera and then go back to whatever she was doing and never think a thing about it.”

And that's not just a man bragging about his mama either. Hilda Stuart's more than 60 years worth of images were recently organized into a lauded exhibition at Duke University's Center for Documentary Studies and published in the book "Choctaw Gardens."

Stuart, 59, shares his mother’s eye for an unforgettable image. Like his mother, he takes photographers that have close ties to intimate moments, friends and family. And you know how country musicians always have a great story about the first time they picked up a guitar? Stuart has the best story ever about the first time he picked up a camera.

In 1970, when Stuart was 11, country music star Connie Smith came to sing at Mississippi’s Choctaw Fair.

“That was a big day for us because she was my mom’s favorite singer,” Stuart recalls. “My mother took me to the department store that morning, and I had her buy me a yellow shirt so Connie Smith would see me.”

The singer didn’t notice Stuart or his shirt during the show, but immediately after the concert, Stuart spotted an opportunity and asked his mother if he could borrow her camera.

“Connie had taken a seat in a car behind the stage,” he says. “I said, ‘Miss Smith, can I take your picture?’ That was the first photograph I ever took.”

It’s a fantastic image: a young Connie Smith, looking radiantly glamorous, sits in the front seat of a car moments before being whisked away from the venue, smiling benignly towards the camera (held, of course, by a kid in a gaudy yellow shirt). On the way home from the concert, Stuart point-blankly informed his mother that he was in love with Connie Smith, and he vowed then and there that one day he would marry her.

Don’t ever let Stuart’s modest, down-home demeanor fool you: He’s nothing if not determined, and he’s a man of his word.

Already an aspiring young guitar and mandolin prodigy at that time, Stuart was discovered early on, and he famously hit the road at the age of 14 with the legendary Lester Flatt and his band. After Flatt retired due to failing health in 1979, Stuart began touring and performing with the likes of Bob Dylan, Vassar Clements, and Doc and Merle Watson, eventually joining Johnny Cash’s band in 1980. Stuart broke out on his own hit-making solo career path in a major way after signing to Columbia Records in 1986. When Connie Smith returned to country music in 1996 after a long absence, she enlisted Stuart’s help in the studio. In spite of the 17 year age difference between them, the two fell in love and married in 1997. Mission accomplished.

Although Stuart’s auspicious first photograph of Connie Smith isn’t included in the Booth exhibition, there’s seemingly an equally fantastic story behind every image in the show. Inspired by the great jazz bassist and famed photographer Milt Hilton, Stuart began snapping images of everything and everyone around him as his country music career developed and blossomed.

“I came to Nashville with a full awareness by way of my mother of how important photography was for memories and just collecting the world around us,” he says. And like Hilton, Stuart had unparalleled access to what was happening behind the scenes in that world.

“The thing that really got me (about Hilton’s jazz photographs) was this picture of Ella Fitzgerald playing dice with the boys. You wouldn’t see that if he weren’t a member of the family … I’ve had unparalleled access to people and situations where a lot of people can’t just walk up and walk in the door. “

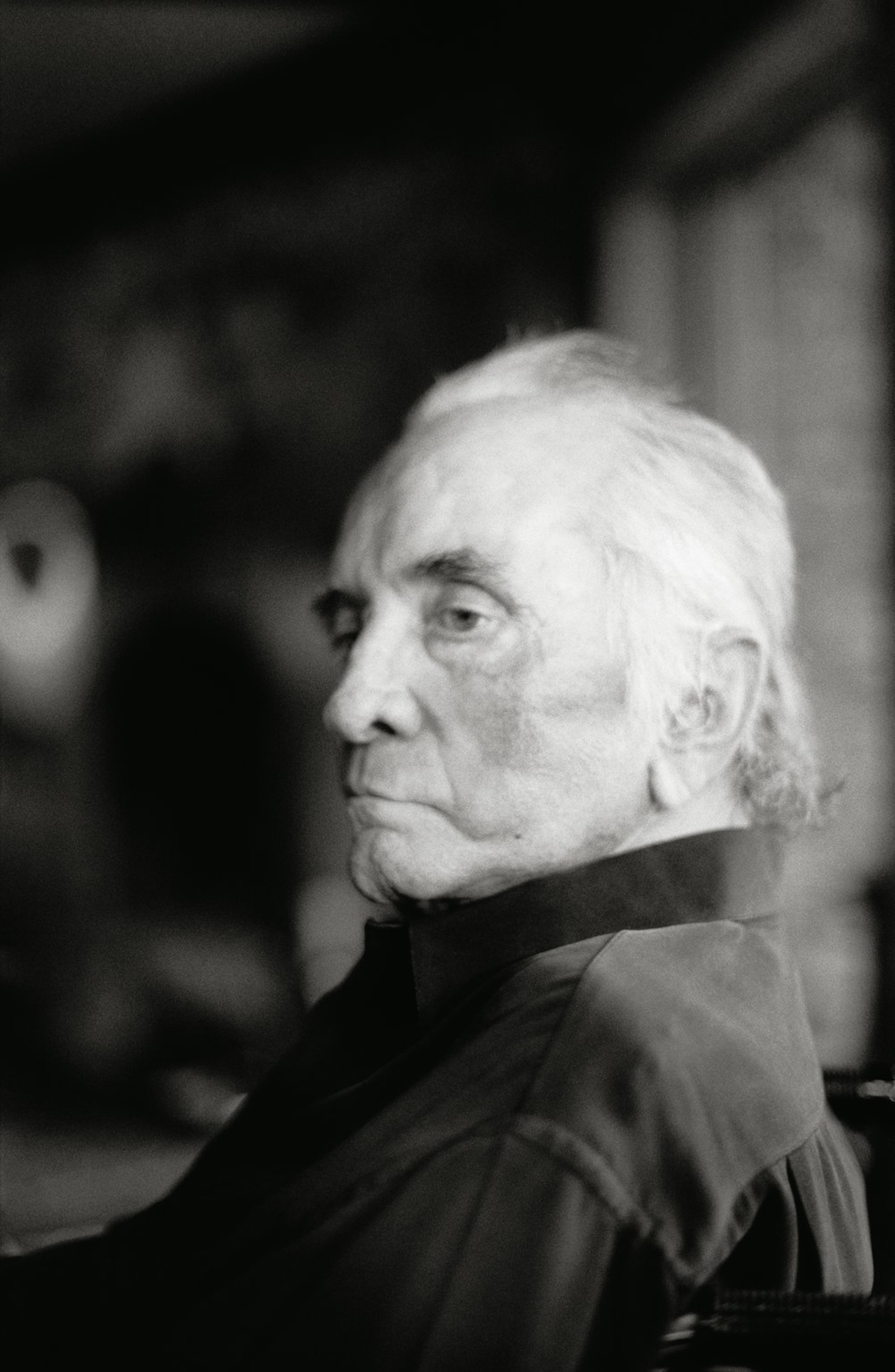

Included in the exhibition are intimate glimpses of such country legends as Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Dolly Parton, Waylon Jennings, Porter Wagoner, Chet Atkins, Carl Perkins, Emmylou Harris, Loretta Lynn, Ernest Tubb, Bill Monroe, Kitty Wells, George Jones and more. Perhaps most unforgettable is an image of Stuart’s lifelong friend Johnny Cash — looking stern, pensive and majestic — taken at Cash’s home just days before his death, the last photograph ever taken of the performer.

Stuart’s photos of country music stars are collected in a section of the exhibition entitled “Masters,” but throughout his career, Stuart has also photographed the unknown heroes and renegades who live on America’s back roads, marked with blue lines on maps. From Elvis impersonators and truck stop oddballs to Dolly Parton lookalikes and small-town preachers, the photographs in the show’s “Blue Line Hotshots” section reveal Stuart’s penchant for capturing the spirit of a vanishing America.

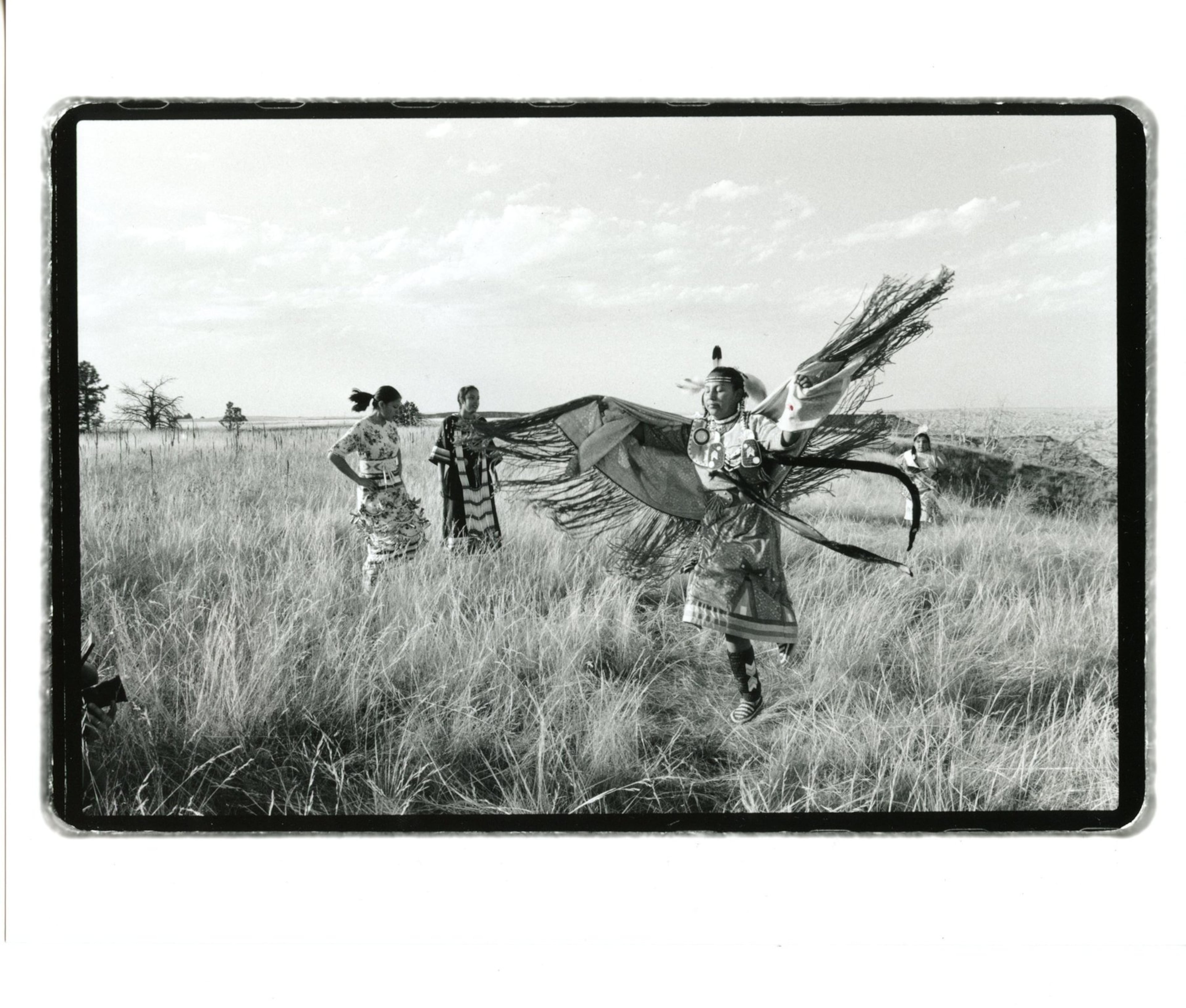

A far more somber mood pervades the third and largest section, “Badlands,” which features Stuart’s images of the Lakota Sioux tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Stuart first visited the tribe in the early 1980s when he was touring with Johnny Cash. He says he was initially puzzled when the tour bus pulled into the tiny dot of a town of Pine Ridge, seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

“I asked John, ‘How come we’re here?’” Stuart says. “He said. ‘Because it’s the poorest county in the US of A. We’re here to show them some love and sing them some songs and let them know we support them.’ I fell in love with those people that night.”

Stuart has continued to visit and photograph the Lakota people throughout his career. He’s been adopted into the tribe under the name of O Yate’ o Chee Ya’ka Hopsila or “The man who helps the people.” He and Connie Smith held their wedding ceremony on the reservation in 1997.

Across all of his work, whatever the subject, whether in music or photography, it’s clear that Stuart sees his creativity as always emerging from the same mysterious wellspring.

“Taking a photograph is like writing a song,” he says. “You start with a blank piece of paper and who knows where you go. There’s no pattern. It just kind of divinely flows. The same with a photograph. Three minutes before you take it, it’s not there, then it’s there forever. The way you write songs and the way you pick up a camera, it has to be framed right, and you have to see the right stuff. It’s such an unexplainable gift. But I’m glad I have it.”

EVENT PREVIEW

'American Ballads: The Photographs of Marty Stuart.' Through Nov. 18. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday. 1-5 p.m. Sunday. $12-$9. Booth Museum of Western Art, 501 N. Museum Drive, Cartersville. 770-387-1300, www.boothmuseum.org.