In compelling blends of photography and painting, Ervin A. Johnson's exhibition "#InHonor: Monoliths" on view at Arnika Dawkins Gallery examines the black experience. "This body of work speaks to the racial violence and discrimination currently occurring across America," says Johnson of his solo exhibition at the Cascade Road gallery.

In formats ranging from tidy 8x10 to inch works to commanding 56x42 inch pieces, Johnson stays consistently focused on the portrait. He sends out calls for subjects on social media and documents a cross-section of black Americans from those queries.

Some of his photographic portraits, often presented unframed on large sheets of paper and tacked to the wall, focus on a single subject. Paint applied to the surface of those images suggests a layer of fairy dust, as with a photograph of a twentysomething woman who shimmers under a blanket of glittery, metallic paint.

At other times Johnson’s subjects are lacquered with a shade of orange-red paint that suggests Georgia clay. In some of those images paint becomes a kind of war paint or a protective veneer. Despite his abiding interest in black faces and black identity, his techniques allow the work to convey a variety of meanings. Johnson’s work can celebrate and protect his subjects. But his use of paint can also suggest an erasure of identity.

One such deeply troubling work, “Monolith #52” features a bearded young man whose face is coated with latte-colored smears of paint so aggressively applied they erase his eyes. The effect is haunting, turning the man into an abstraction, perhaps to reflect how fundamentally society renders black men alien and menacing.

Johnson’s portraits operate on one level as a profound assertion of black identity; a way to revel in images of people not always considered in art history. The photographs are exceedingly intimate with Johnson’s subjects meeting our gaze and staring back as we ponder their faces.

MORE ON AJC.COM: Atlanta exhibit shows off world of black Southern cowboys

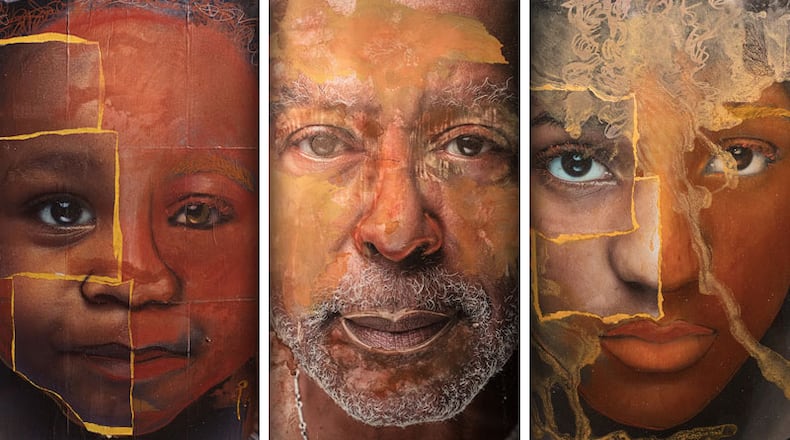

In other cases, collage is Johnson’s focus.

In those combinations of various photographs Frankensteined together, the artist blends features from various people into one — an eye from one man superimposed onto a portrait of a child, even Johnson’s own features inserted here and there. Suggesting African masks or Cubist collage (the Cubists themselves were also greatly influenced by African art) those bricolage photographs create a portrait of a community. They equalize their subjects, endowing them with a shared experience; the experience of being black in America. Blackness is not singular in these portraits. Instead, it is a unifying condition shared by a little girl and by an older man and by a teenage boy who share the associations and expectations of society in the circumstance of their skin color.

Johnson’s stated mission in “#InHonor: Monoliths” is to describe a black experience that today is informed by a far-from-neutral sense of injustice and embattlement. For Johnson, the #BlackLivesMatter movement (from which the artist draws his own hashtag title) has articulated the sense of threat and injustice many black Americans feel. “This body of work speaks to the racial violence and discrimination currently occurring across America, particularly in the form of police brutality,” Johnson states of his ambition for the show.

If the portraits themselves did not convey the sense of wariness and watchfulness in his subjects, then a gallery room wall onto which Johnson has written his stream of consciousness thoughts about the profound, unsettling, enraging effects of racism makes his ambition clear.

Johnson’s show exemplifies the power of portraiture. “#InHonor: Monoliths” is an opportunity for gallery-goers to, for a time, inhabit another person’s consciousness and imagination and ponder the life and experience of strangers.

Art Review

“#InHonor: Monoliths”

Through February 7, 2020. Wednesdays-Fridays 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Free. Arnika Dawkins Gallery, 4600 Cascade Road, Atlanta. 404-333-0312, adawkinsgallery.com

Bottom line: Ervin A. Johnson’s mixed-media photographs are politically relevant meditations on black identity and racism.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured