Georgia students’ private battle: Anxiety disorders in the classroom

Latha Wright studies Latin, draws her own comics and films videos with her little brother.

The 16-year-old Atlanta student also battles anxiety.

When her family sought help, they encountered obstacles that make it difficult for many Georgia teens and young adults to get therapy and proper medication.

Her mom, Sherry Neal, called numerous providers covered by their insurance in her search to find someone taking new clients.

Navigating health care in general is hard, she said, but: “Just wait until someone you love needs mental health care.”

During the pandemic, rates of anxiety disorders and depression among young people doubled to 1 in 5, according to JAMA Pediatrics data. The social isolation of virtual learning, social media pressures and academic expectations are primary contributors.

“We’re putting our kids in these incubators of pressure,” said licensed psychologist Josh Spitalnick of Anxiety Specialists of Atlanta. “(It’s) not surprising that we’re seeing more families in a clinic like ours.”

While everyone gets anxious occasionally, for some students it’s a crippling disorder that disrupts home, school and social activities. Left untreated, it can lead to depression, suicidal thoughts and other mental health issues into adulthood.

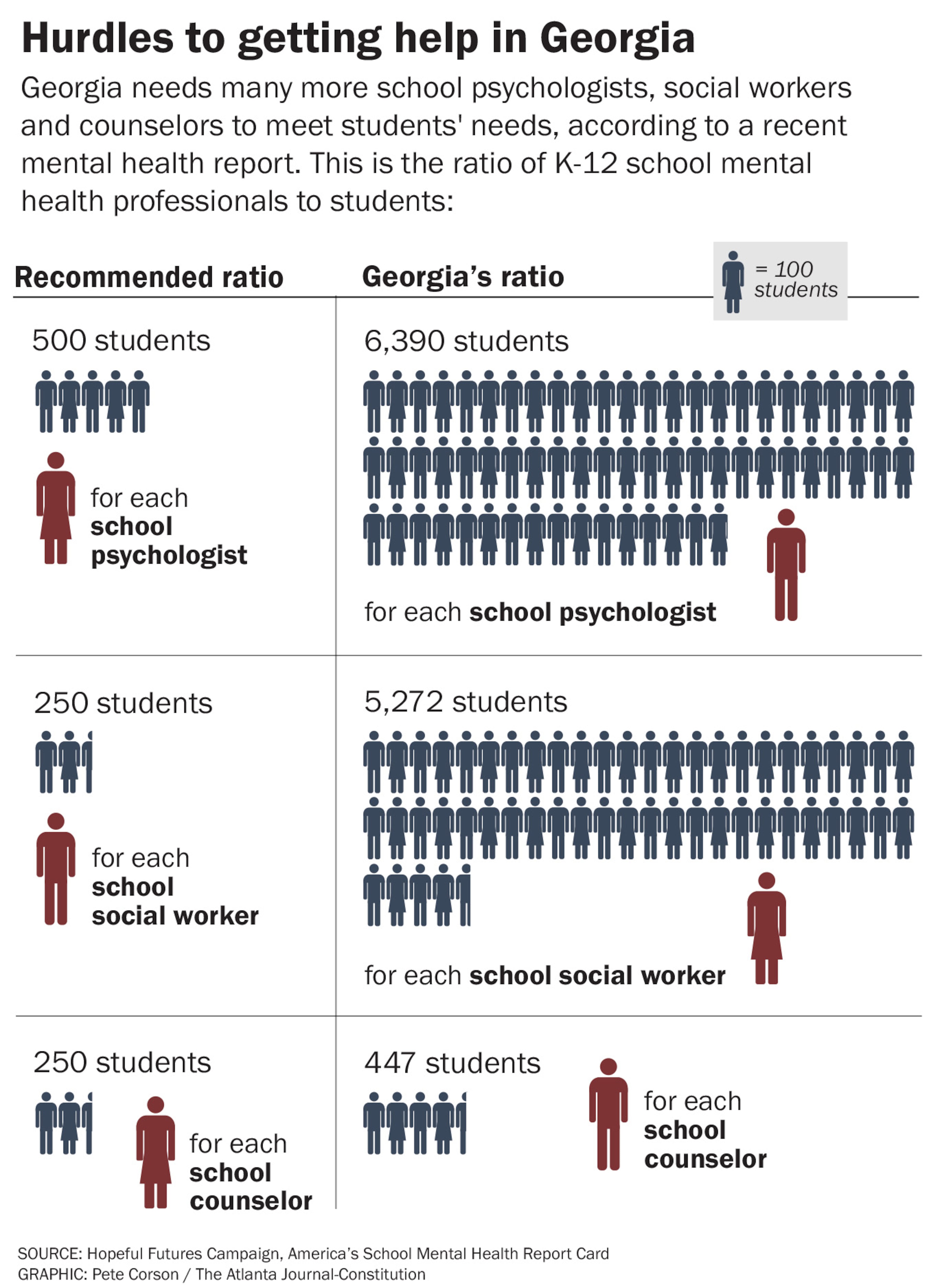

Georgia schools and colleges are now spending more money for mental health services. But the state is far below recommended standards for the ratio of mental health providers to students on the K-12 and college level.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution a collective effort is needed to increase counselors in schools, peer support programs and online treatment services to address youth anxiety.

”We have to go big and do this with urgency,” he said, so “people can ask for help when they need it and that care is actually available to them.”

Obstacles to care

During eighth grade, Latha missed numerous school days with an upset stomach — a common symptom of an anxiety disorder — and respiratory problems. Doctors ran several tests, but could not pinpoint an illness.

Eventually, she was diagnosed with anxiety and panic disorders, and later depression.

Latha, with her parents’ support, sought therapy after a breakdown. It happened as her parents were about to open her ninth grade report card. The high-achieving student was upset about one of her grades and ran out of the house.

“I just hid. I was so scared what would happen if they found out that I had a C,” she said.

Her mother said it was hard to find a therapist who would take their insurance and a psychiatrist who was accepting new patients.

About anxiety disorders

An anxiety disorder is often characterized by extreme responses to or fears about everyday events. Symptoms can include changes in sleeping patterns and difficulty focusing. Left untreated, it can lead to depression, other mental health issues or suicidal thoughts.

Common symptoms

- feeling weak, tired or withdrawn

- gastrointestinal problems

- increased heart rate

- rapid breathing

- trouble sleeping

Source: The Mayo Clinic

Georgia has only eight psychiatrists per 100,000 children, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The recommended ratio is 47 per 100,000.

Some families who live outside metro Atlanta travel far to find a good match with a child psychiatrist. When Bev Rogers of Columbus, Georgia, looked for help for her now 18-year-old son, she finally found someone 100 miles away in Decatur.

“You’ve got to be a fighter, and you’ve got to be somebody who doesn’t take no for an answer,” Rogers said.

Neal said they considered hospitalizing Latha to get her care. After about 15 calls and a friend’s recommendation, they found a psychiatrist to prescribe and manage medication. The family pays out-of-pocket for those visits.

Now, Latha feels less despondent, and she’s had fewer panic attacks.

She’s still susceptible to getting sick, and said her anxiety contributes to head and stomachaches. At school, she has a support plan that allows her to turn in assignments late without penalties.

But Latha said mental health is still misunderstood.

“For some reason, you’re allowed to miss school if you’re physically sick,” she said. “But if you’re super depressed or if you had a really bad anxiety attack the night before … it’s not excused.”

Insurance disparities

Gov. Brian Kemp recently signed into law bipartisan legislation aimed at enforcing a federal mandate requiring parity in health coverage. That’s because Georgia insurance companies aren’t covering mental health care costs at the same levels as physical health care.

Some mental health professionals no longer accept as many insurance plans as they once did. They say insurers often require burdensome paperwork and pay far less than the going rate. That makes it hard for some families to afford therapy, which can cost $150 or more per session.

Alan Behrman, a Marietta-based psychologist, said insurance companies have become more difficult to deal with because they refuse to pay for services or cover less.

“The majority of the therapists I know … are dumping all the insurance panels left and right, and they’re going strictly private pay,” he said.

Kristin Lamote of Cumming struggled to find a therapist covered by her insurance for her 16-year-old son. She found a therapist who accepts her insurance, but still pays $85 for each session until her $1,500 deductible is met.

“If you can’t find someone that does take your insurance, you either don’t go or you go very sparingly,” she said.

Lamote said therapy, combined with proper medication, has helped her son’s anxiety disorder, signs of which included moodiness, excessive cleaning and one scary instance when he couldn’t catch his breath.

The new mental health care law will result in health care organizations spending more money on treatment for low-income Georgians, said Kim H. Jones, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Georgia. Georgia providers spend less on care than neighboring states, she said.

Jones believes the bill will help much of Georgia, but worries about rural areas without broadband where families can’t access telehealth counseling services.

“I think this bill will help a lot. The problem is it will not help fast enough,” she said.

Meeting the demand

For some students, worsening anxiety disrupts their education.

Brooke Hartman left her Fulton County high school during her freshman year to focus on her mental health. Following a difficult stay at a psychiatric hospital, she later was diagnosed with generalized anxiety and persistent depressive disorders.

Her mom, Ruth, tapped into a local-mom network to find help: “We wasted so much time at one of the facilities because it wasn’t the right kind of therapy.”

Schools play a critical role in supporting students’ mental health, but Georgia lags when it comes to school-based mental health providers.

There’s only one school psychologist for every 6,390 K-12 Georgia students, far fewer than the one for every 500 recommended, according to a recent national report by a group of mental health agencies. Schools also need more counselors and social workers, they say.

The University of Georgia has 20 full-time clinicians in its counseling center — about one for every 2,000 students. That’s less than the ratio of one staff person for every 1,000 to 1,500 students recommended by the International Accreditation of Counseling Services. In addition, UGA has clinicians in some academic departments.

Metro Atlanta districts have added staff though they’re still below recommended levels. Atlanta Public Schools last year budgeted $2.8 million to hire 25 more social workers and plans to hire more psychologists next year.

As the need grows, counseling agencies that work in schools are struggling to hire and retain personnel. Some are leaving due to burnout or because they can earn more and enjoy more flexibility if they go into private practice.

When Brooke was ready to resume school, a supportive literature teacher adjusted her assignments. While the rest of the class read “Romeo and Juliet,” the teacher allowed Brooke to study a lighter modern musical.

Brooke’s sophomore year was exponentially better. She’s allowed to listen to music or step out of the classroom when she feels anxious.

“At first I resisted treatment, but that didn’t get me anywhere,” said Brooke. “At the end of the day, I’m a much happier person.”

Diversity concerns

Georgia colleges are struggling to help some students, particularly men and students of color.

Just 30% of students seeking mental health services on college campuses are men, according to a 2021 Penn State report.

The percentage was lower this year at Kennesaw State, despite outreach efforts. Josh Gunn, executive director of its counseling services, attributed part of the drop-off to the isolation created by the pandemic.

“You throw a lot of complicated life stuff on top of it and they’re less likely to reach out,” he said.

Part of the problem is that students don’t seek help or don’t show up for appointments. Some feel there’s a stigma attached to it.

“They request services … but they don’t always follow through,” said Vickie Jester, director of Clark Atlanta University’s counseling and disability services center.

Many students at Georgia’s historically Black colleges and universities faced another challenge this past semester with bomb threats that prompted campus lockdowns.

Marcellus Kirkland, who helped lead protests last year for better housing at HBCUs, said students give the colleges mixed grades for their mental health services. Kirkland, who graduated last month from Morehouse College, said the schools stress the importance of self-care, but don’t aggressively promote their own counseling services.

Kennesaw State student Tyler Ricks is spreading the word about mental health services on campus, encouraging classmates to seek counseling.

Ricks sought counseling for anxiety when she began taking classes there in 2019. She was eventually diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and is still getting help.

She describes herself as a perfectionist and felt anxious as finals approached this spring. Everything, she said, feels high stakes.

Ricks recalled feeling “trapped” during the pandemic’s early days, when classes and her counseling sessions were held remotely. But she was initially unsure the counselor assigned to her could connect with her. He’s white. She’s Black.

“Can he really help me?” Ricks wondered.

He did help.

“I just want to see that same change for other people because I know it is possible now,” she said.