Tyler Perry Studios plans expansion

An executive with Tyler Perry Studios announced plans Thursday for an expansion that could nearly double the size of the film and television campus near Greenbriar Mall in southwest Atlanta.

Details of the $200 million expansion plans were not revealed. However, the studio executive said Perry controls an additional 30 acres adjacent to his 30-acre-plus campus.

“For now, we are just in the design phase,” said the executive, later identified by a state official as William Areu. He said Perry would have more to disclose about the project in coming months.

Areu’s comments were made during a public meeting the state’s Department of Economic Development board at Perry’s heavily secured compound, access to which required attendees to sign a confidentiality agreement. The agreement restricted what information could be disclosed about Perry and his operations.

It’s an unusual restriction to be put on attendees of a public government meeting. Two legal experts told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution it might have violated the Georgia Open Meetings Law.

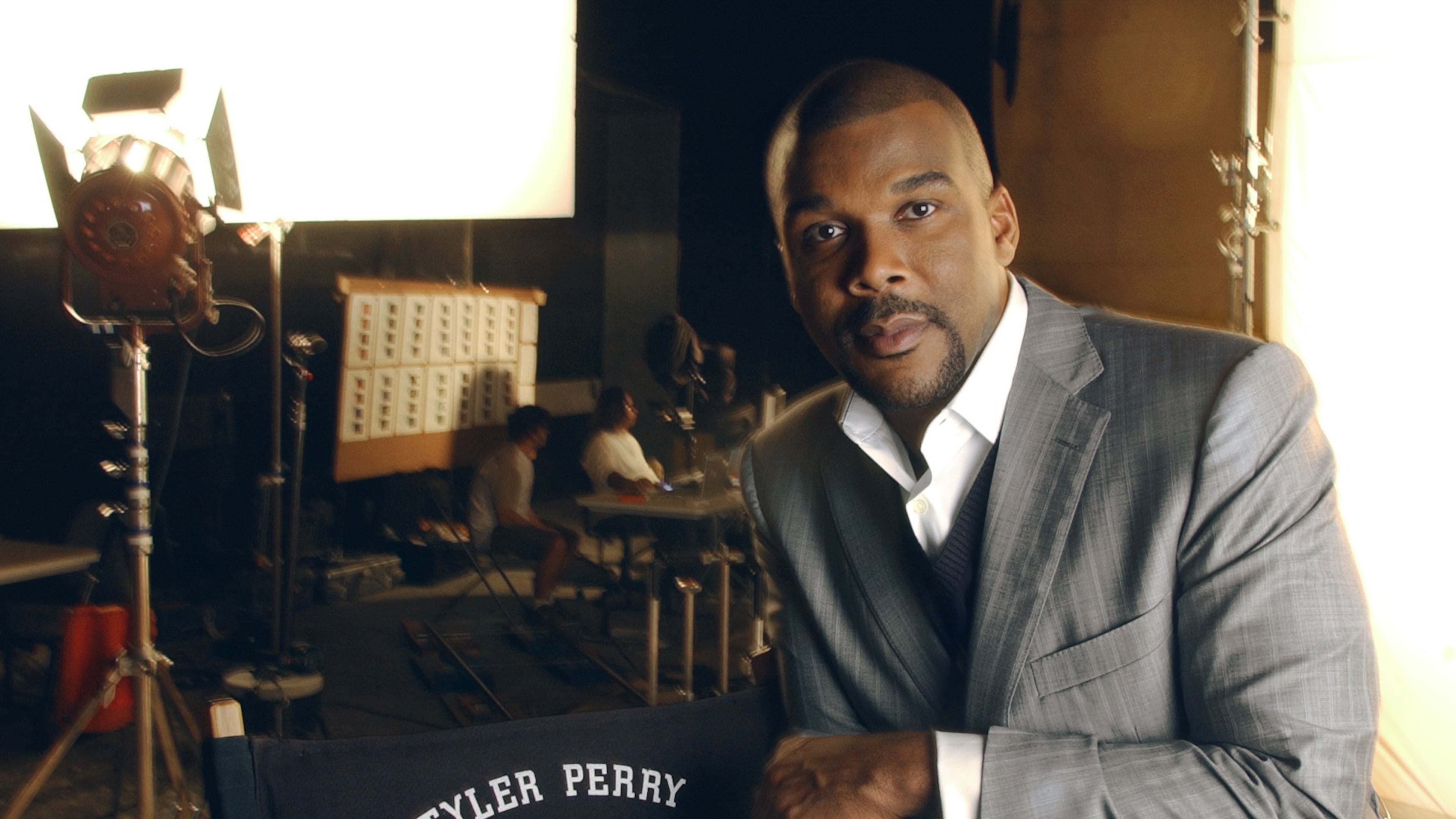

Perry is the prolific writer, director, actor and producer behind the “Madea” film series and several television series, including “Meet the Browns.” He has grown from a struggling playwright who moved to metro Atlanta in the early 1990s into an entertainment mogul.

Perry told Entertainment Tonight last April he planned a “huge expansion” of his operations, including new sound stages for production. Meanwhile, the AJC also has reported a firm with ties to Perry has made multiple land purchases in Douglas County near Sweetwater Creek, about 10 miles west of Six Flags Over Georgia.

A message left with Perry’s representatives in Los Angeles was not immediately returned.

Perry briefly appeared at the state meeting Thursday and said he has invested $200 million in Georgia through his various entertainment ventures.

He praised the state’s film tax credits, which he said is shifting business from Hollywood to Georgia, creating local jobs and investment.

“If you only knew the houses and cars and kids that are going to college” because of opportunities created by the credits, he said, “and how happy these people are coming to work every day.”

Production companies can earn a credit of up to 30 percent of what they spend on qualifying projects. What they can’t use to defer their own taxes — many aren’t based here and have little tax liability — they can sell for cash at upward of 90 cents on the dollar. Companies that buy the credits can then use them to reduce their Georgia tax bills.

Gov. Nathan Deal, who, like Perry, briefly attended the meeting, told the board that the film tax credits are bringing not only film and television production, but it’s starting to bring editing and other types of post-production activities.

“What you just heard is the kind of migration of employment that is necessary for this to be an industry of permanence,” Deal told the board.

Eleven production studio projects or expansions have been announced in Georgia since 2010, and more than 70 film services companies have relocated or expanded here, Deal said.

Chris Carr, the commissioner of the state Department of Economic Development, said the agency’s board decided to hold its regular meeting at Perry’s private studios to spotlight growth of the entertainment industry. The visit included a tour for the board.

But in doing so, state officials told the media that they would be barred from the property without first signing a six-page confidentiality agreement that Perry requires of all visitors.

“Any restriction on access to the physical place of a public meeting violates the Open Meetings Act,” said Hollie Manheimer, the executive director of the Georgia First Amendment Foundation. “The point of the Open Meetings Act is for citizens to monitor their own government. Since there are impediments to that, that is an impediment or barrier to the Open Meetings Act.”

David Hudson, a lawyer for the Georgia Press Association, said, “I’ve never heard of any restriction like this that was imposed on a meeting that should be open to the public.

“My view was it would be a contravention of the Open Meetings Act for a meeting to be conducted in any place that had these types of restraints on public access and public activities,” he said.

Carr, the economic development chief, said in a telephone interview after the meeting that the agency followed the advice of the state Attorney General’s office. The agency made the meeting open to the public both on-site (for those people who signed a confidentiality agreement), and by watching online via Skype, from a conference room at the agency’s Midtown Atlanta headquarters. No member of the general public or media was at the studio for the meeting, state officials said.

“We went over and above” the requirements of the law, Carr said. The state chose Perry’s studios to try to attract media attention, not to stymie it, he said.

The AJC refused to sign the document, and instead a reporter listened in via a Skype conference call. But the proceedings were difficult to follow, as the audio and visual quality of the meeting was poor.

It was often difficult to discern who was speaking or to make out what was said.