Newcomers driving north on Atlanta Highway could feel disoriented. For roughly two miles, many of the colorful signs are in Spanish. Taquerias beckon motorists with chorizo, carne asada and al pastor tacos. The crowded Viajes Latinos travel agency advertises boletos de avión, plane tickets. Lavanderías — coin laundries — pitch agua caliente, hot water.

About 50 miles northeast of Atlanta, this bustling commercial stretch goes by “Little Mexico.” Gainesville’s Hispanic population has nearly doubled since the 2000 census and now represents 40% of the city’s 41,464 residents. Many Latinos work in the poultry industry, a major economic engine.

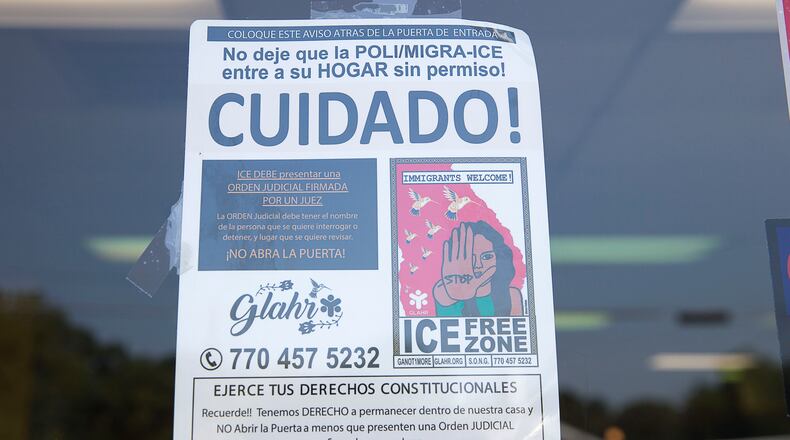

Some 12% of the metro area's residents lacked legal status in 2016, the highest rate in the nation, according to one study. Surrounding Hall County, which voted 74% for Donald Trump in 2016, is one of just five counties in Georgia participating in a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement program that is deporting increasing numbers of people here.

The region vividly illustrates the tension between upholding the rule of law under Trump’s crackdown on illegal immigration and scaring away workers who are keeping the economy booming.

When Trump threatened nationwide immigration enforcement raids in July, business slowed along Atlanta Highway as immigrants with and without legal papers — many have mixed-status families — stayed home from work and did not spend their money. Last month, hundreds of panicked poultry workers in Gainesville — nicknamed "The Poultry Capital of the World" — fled their jobs amid a rumored immigration roundup.

John Hulsey, who voted for Trump in 2016 and supports the president’s border wall, reflected on the conundrum as he sipped coffee at Longstreet Café, named after a Confederate general. Hulsey employs Hispanic workers at his Hall County-based plumbing and environmental services firm, which serves the poultry industry.

“They are hard workers,” he said of his Latino employees.“I could not run my business without them.”

Hulsey emphasized he uses E-Verify, a federal work authorization program. But he added he could double his business if he could find more qualified workers. The government, he said, should find a way to bring in more from other countries legally.

Waiting on Hulsey’s table was Maricindi Jaramillo, who said she was brought here illegally by her parents from Mexico when she was six. Jaramillo has been granted a special reprieve from deportation and a work permit through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which Trump has sought to cancel. Taxes are regularly deducted from the East Hall High School graduate’s paychecks to pay for entitlement programs closed to her because she lacks legal status. Her eight-year-old son was born here, making him a U.S. citizen.

“I bought a house. I have my car,” said Jaramillo, whose mother worked in a Gainesville-area poultry plant. “That question is always there: Am I doing all this for something or am I going to lose everything?”

‘They just all walked out’

Georgia is the largest poultry producing state in the nation, with many of the plants clustered around Gainesville. So it's little surprise the tremors were felt here in August after federal authorities executed search warrants at seven poultry industry sites across Mississippi, arresting 680 people suspected of being in the country illegally.

Tom Hensley, president of Baldwin-based Fieldale Farms, a major poultry company and one of the largest employers in Hall County, estimated about 400 workers fled last month from two separately owned chicken processing plants his company depends on in Gainesville after a rumor spread of an immigration enforcement raid. He said the plants belong to Victory Processing and Gold Creek, estimating the losses at a few thousand dollars.

Victory Processing did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Gold Creek said in a statement it complies with state and federal hiring laws and uses E-Verify.

Photos from inside one of the empty plants that day, Hensley said, show “hairnets on the floor and chicken on the tables.”

“They just all walked out at the same time,” he said of the workers.

The poultry industry is significantly understaffed, he added, partly because of the physically taxing work, low unemployment and fear surrounding the Trump administration’s clampdown.

“We could use 300 more people tomorrow,” he said, “if they were available to hire, but they are not.”

Gainesville Mayor Danny Dunagan declined to comment.

Not every Latino here works in the poultry industry. But many have, or know somebody who does.

Norma Hernandez works out of a little yellow house with a columned front porch around the corner from a Hispanic church on Atlanta Highway. This is where she operates her many businesses: bookkeeping and tax preparation, title pawn, courtroom translation and financial planning.

Hernandez legally immigrated here from Honduras 30 years ago, following a sister who married a jeweler from Gainesville. She found one of her first jobs packing chicken at a nearby poultry plant. Later, she served as a dispatcher and Spanish interpreter for the Gainesville Police Department, a probation officer and municipal court clerk. Eventually, she went to work for herself.

“We all have to start at the bottom,” said Hernandez, who created the Northeast Georgia Latino Chamber of Commerce about a year and a half ago. “We all started working in the poultry plants, just about everybody.”

When workers fled the poultry plants here last month, Jose Diaz said business was down by nearly half at the two taxicab companies he co-owns, La Nueva Tijuana and La Libertad. He employs about 20 people.

“For three days, it was very slow everywhere,” said Diaz, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Mexico whose taxis serve Gainesville’s poultry plant employees. “Nobody called. Everybody was staying home.”

Perla Medrano and her husband — she was born in the United States and they both have Mexican heritage — started their homemade ice cream business on Atlanta Highway 17 years ago. They now have three other La Mejor de Michoacan locations and a warehouse, employ up to 30 people and earn $1 million in annual revenue. One of their popular flavors is mango with chamoy, a sauce made from fermented fruit and chiles. When there are worries about looming immigration enforcement, Medrano said, “These streets are clean. Nobody goes anywhere. Everybody gets affected.”

The jail

Down Barber Road, near the southern tip of Gainesville and past a few jail bond businesses and the county’s animal shelter, sits the sand-colored county jail. Rimmed with barbed wire, the lockup is where ICE operates its 287(g) immigration enforcement program with the help of county sheriff’s deputies. It is named after the 1996 federal law that authorized it.

The program deputizes local officials to help enforce federal immigration laws in jails like this one, giving them the authority to investigate and detain people facing deportation. Proponents say it helps deter illegal immigration, while critics argue it splits up immigrant families and makes them fear reporting crimes to police.

The number of people deported after being detected by the program in the county jail more than quadrupled between fiscal years 2016 and 2018, from 45 to 185. Some 106 have been deported through April 1 of this fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30.

Gainesville police officers, who are separate from the county Sheriff’s Office, stress in their meetings with civic groups and local churches that they are not immigration officials, said Sgt. Kevin Holbrook, a spokesman. He added his department includes Hispanic officers and chaplains and offers pay incentives for bilingual employees.

Last month, the English singer Adele’s photo popped up on the police department’s Facebook page with a headline borrowing from the title of her hit song, “Rumor has it.” The post was a playful effort to dispel a rumor “circulating around our agency’s involvement with food processing plants.”

It’s a tricky situation for Hall Sheriff Gerald Couch, who is seeking close ties with the area’s immigrant communities while cooperating with ICE. The 287(g) program, he said, helps protect public safety.

“We want to make certain that we do have good relationships with everyone in our community, and if they are victims of crime, we want that reported,” he said. “We don’t want anything to have a chilling effect to harm that relationship.”

Art Gallegos Jr., a bilingual food bank coordinator from Gainesville, supports the local sheriff.

“The fear that they are out to get you… because you are from a different race — that is nonsense,” said Gallegos, a Republican who voted for Trump and who leads the local Latinos Conservative Organization.

Maria del Rosario Palacios, a naturalized U.S. citizen and daughter of migrant Mexican workers, sees it differently.

“The poultry capital of the world would not be the poultry capital of the world without undocumented immigrants. End 287(g),” the former statehouse candidate said in a Facebook video last month, standing in front of Gainesville’s marble “Poultry Capital of the World” monument.

In May, Couch and ICE signed an agreement renewing for another year the county’s 287(g) program.

Gainesville, Ga., by the numbers

Population: 41,464

Hispanic: 40%

Foreign-born: 25%

Share of total population for the Gainesville metro area that are unauthorized immigrants in 2016: 12%

Share of the foreign-born population in the Gainesville metro area that are unauthorized immigrants in 2016: 65%

Top 10 Employers in Gainesville-Hall County/Employees in 2018

1. Northeast Georgia Medical Center, 8,331

2. Hall County School District, 3,500

3. *Fieldale Farms Corporation, 2,550

4. *Victory Processing LLC, 1,730

5. Hall County Government, 1,706

6. Kubota Manufacturing of America, 1,695

7. *Pilgrim’s, 1,380

8. *Gold Creek Foods, 1,300

9. *Mar-Jac Poultry Inc., 1,280

10. ZF Gainesville LLC, 1,045

* Poultry industry.

Deportations of people encountered through the 287(g) program in the Hall County Jail by fiscal year.

*2019: 106

2018: 185

2017: 142

2016: 45

2015: 73

2014: 163

*As of April 1.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, the Pew Research Center, the Greater Hall Chamber of Commerce and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured