Perhaps you didn't notice, but a pair of events gave significant form and substance to the 2017 race for mayor of Atlanta last week.

On Tuesday, Gov. Nathan Deal signed into law a measure that would allow a $2.5 billion expansion of MARTA within the city limits of Atlanta. Should voters approve in November, the biggest facelift the city has seen since the late 1970s is likely to include a light rail system along a new Beltline.

Upon first taking office, the last two mayors of Georgia’s capital city were beset by unseen and largely unappreciated crises. Shirley Franklin became the “sewer mayor.” Kasim Reed spent his honeymoon capital on the repair of a broken pension system.

By contrast, the next mayor could have tremendous — and immediate — say-so over a highly visible, job-generating explosion of transit options. By rights, the prospect of being at the helm of such a resurgence ought to give next year’s contest an upbeat, optimistic feel. And it surely could.

Yet in another development, on Monday, the day before the governor signed the MARTA bill, Peter Aman publicly announced as a candidate to replace Mayor Reed.

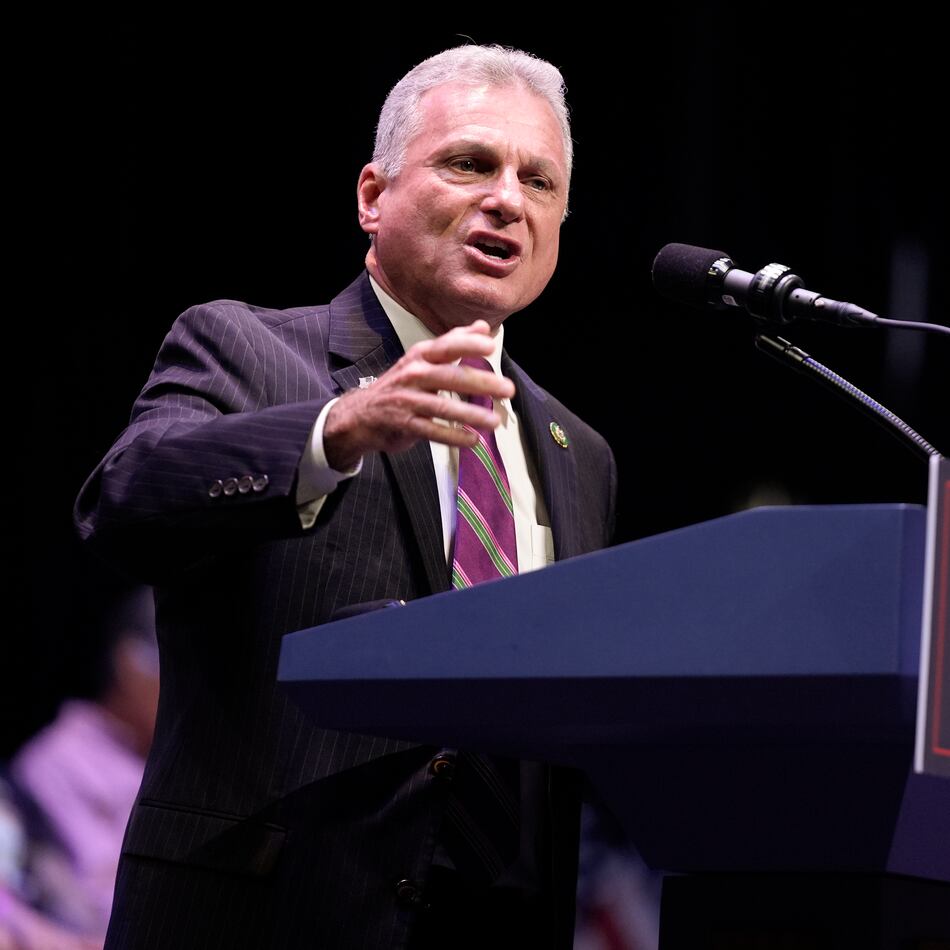

Now, let us be clear: As a person and candidate, Aman is no buzz kill. Far from it. He is an optimistic and upbeat fellow. He served as Reed’s chief operating officer, overseeing all city departments and 7,000 employees. A partner at Bain & Co., a global consulting firm, Aman served as an unpaid budget trouble-shooter and more in the Franklin administration. He knows how the city works.

It is not who Aman is, but what he represents. He has just become the first white Protestant male to make a serious play for City Hall since the 1973. That’s when former congressman Charles Weltner narrowly lost a runoff spot to Jewish incumbent Sam Massell, who was in turn defeated by Maynard Jackson. If successful, Aman would end four decades of African-American political dominance that began with that contest.

So race will be as much a topic in next year’s mayoral campaign as the MARTA makeover.

That Atlanta has been undergoing a shift in its political demographics is no secret. In the 2009 runoff, Reed beat Mary Norwood, a white city councilwoman, by only a few hundred votes, out of more than 80,000 cast.

Norwood may run for mayor again next year, joining a field that already includes Aman and five others: Ceasar Mitchell, president of the Atlanta City Council; state Rep. Margaret Kaiser; and Cathy Woolard, a lobbyist for Georgia Equality and a former council president. State Sen. Vincent Fort could also join the fray, as well as Kwanza Hall and Keisha Lance Bottoms, both city council members.

Of those eight, half are black, half are white.

In that field, Aman would stand out — not only as the only white male, but as the one candidate without significant electoral experience. He’s never run for public office before.

At this point, the wealthy businessman-stranger running for public office is something of a cliché. On the Republican side, David Perdue did it with a blue-jean jacket in the 2014 race for U.S. Senate, providing an example for Donald Trump this year.

Georgia Democrats have fielded Jim Barksdale, founder of an Atlanta equity firm who has loaned himself $1.1 million to finance his run for U.S. Senate against Republican incumbent Johnny Isakson.

“I don’t consider myself part of that movement. What I consider myself is a hybrid at the intersection of the public sector and the private sector,” said Aman, 49, in an interview this week. “I’m running as the guy that can use the tools that the private sector has, where appropriate, but has a deep understanding of how government works — and what’s different about it. Government isn’t a business.”

Nor is Aman going to rely on his own wealth to fuel his campaign. ”Being a self-funder yields a sub-optimal candidate,” he said.

In that 2009 mayoral race, the Georgia Democratic party entered the contest on the side of Kasim Reed, accusing Norwood of being a closet Republican. That shoe in no way fits Aman.

Reed has pitched him as a potential Democratic challenger to Isakson. Clearly, Aman had other ambitions. As a mayoral candidate, Aman has also promised not only to protect, but to expand the city’s policy of reserving some contracts for businesses owned by women or minorities — to make sure they get a piece of the pie.

But Aman concedes that the color of his skin will be a topic of much conversation — even among an electorate that is now feeling a little bit of wind at its back.

“You have to acknowledge that this is a huge deal. There are a tremendous number of people who are uncomfortable with the notion of a white mayor. I hear that,” Aman said. “I do know that for much of the campaign there will be discussion around this. Race is a difficult discussion to have between two people at home around a coffee table.

“It’s an even harder conversation to have when you’re in the middle of a public process, when you’re a candidate,” Aman said. “The more open we are, the better off we’ll be.”

We have 18 months to figure out how to pull that conversation off. Think of it as the spice in a MARTA-sweetened political season.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured