Myra Blackmon is a retired public relations professional with both a bachelor's of arts in journalism and a master's in education from the University of Georgia. She and her husband recently moved back to her hometown of Washington, Ga., after several decades in Athens.

By Myra Blackmon

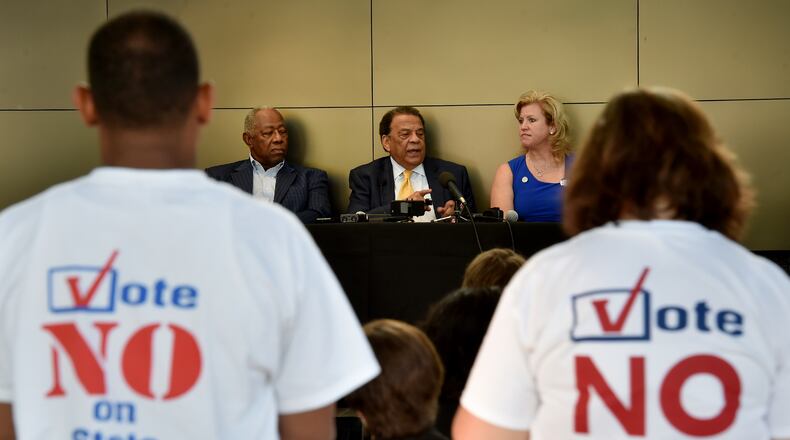

Tuesday's lopsided defeat of the proposed Opportunity School District constitutional amendment in Georgia illustrated a rare phenomenon in the United States these days: people normally on opposite sides came together on an education issue.

Liberals and conservatives, rural and urban residents, people of all races decided that a state takeover of local schools deemed poor performers is not a tolerable solution. At the same time, there was no ballot initiative that let people weigh in on exactly how they want to improved education.

Georgians have a unique opportunity to continue to work across partisan and demographic lines to address problems in schools that serve large populations of poor people in communities that often lack resources. There are several possibilities for this unusual alliance to continue its newfound influence.

First, we can use the same techniques to insist the Legislature fully fund the Quality Basic Education formula that promises equitable and sufficient funding for all schools. Changing the formula will do no good if we don’t know what would happen if we actually funded the one we have had in place for decades. We must also insist that money that would have been spent on the Opportunity School District be used to help those 127 schools on the original target list.

Second, we must advocate for allowing the state Department of Education to do its job. As state School Superintendent Richard Woods outlined in a recent piece, the state DOE has the knowledge and expertise to help struggling schools improve their performance. In recent years, however, the governor and the Legislature have regularly bypassed the DOE and its elected head, imposing new rules and ignoring any input from the one department of state government that has the personnel, experience and reach most likely to help solve our problems.

Third, we must insist on appropriate assessment of school performance. The College and Career Ready Performance Index is being misused to "grade schools" as passing or failing when it was designed to simply measure growth. Further, the CCRPI wrongly relies almost entirely on the results of the Georgia Milestones standardized tests.

Despite the hundreds of millions of our tax dollars invested in the Georgia Milestones, the tests have never been validated as reliable measures of education. That is, they have never been put through the statistical process that guarantees that the questions actually measure what they are intended to. For the last two years, at least portions of the test results have been completely unusable; the tests themselves have changed annually and the results provide no diagnostic information to help teachers zero in on what students need. The test is used punitively when a more effective use would be to provide individual data that would allow schools to tailor instruction to student needs.

Finally, the organizations and volunteers who joined to defeat the amendment can continue their work to help school boards, systems and teachers who need additional training and support to improve their performance. Members of school boards in innovative districts can mentor members of boards in communities that may need help instituting changes; volunteers can raise money and contribute expertise to provide extra coaching and tools for new teachers or those who work in the most challenging environments.

The defeat of Amendment 1 showed that Georgian are capable of putting aside ideology to focus on a common goal. We must maintain that forward movement to be sure every Georgia student has access to a world-class education.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured