Alvin J. Schexnider is a former chancellor of Winston-Salem State University. He is a senior fellow at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges and author of "Saving Black Colleges."

By Alvin J. Schexnider

The recent meeting of President Donald Trump with black college presidents cast a spotlight on this important sector of American higher education. With nine out of 10 African-American students enrolled in majority schools, historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs as they are commonly known, are indisputably imperiled.

During the meeting, the president approved an executive order moving the federal initiative on HBCUs to the White House from the Department of Education. A request of $25 billion dollars to help with scholarships, technology and facilities was also submitted.

Higher education does not appear to be one of this administration’s budget priorities so a favorable response is questionable. Black colleges are not monolithic and needs tend to vary. Some schools are independent; some are public. A few are research and doctoral-granting institutions. Some boast solid academic reputations and sound financial footing yet many struggle to stay afloat. Dwindling enrollments and small endowments make several vulnerable without an infusion of federal aid.

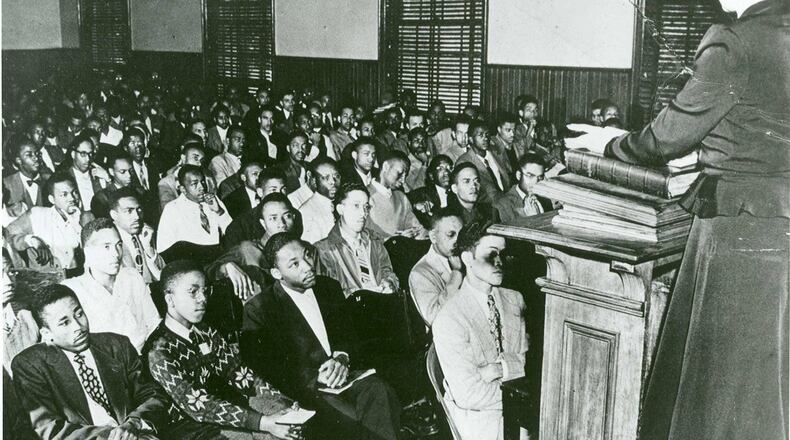

Black colleges and universities are iconic institutions. Several are in the midst of sesquicentennial celebrations, a feat in and of itself given the huge challenges they have surmounted from the beginning. HBCUs were founded during a period of hostile, entrenched and enforced segregation. Of necessity black colleges depended on white philanthropy and later state government for financial support. They enjoyed a pure monopoly on students and employees.

Desegregation has altered the landscape and today many, if not most, struggle to survive haunted by memories of the demise of black businesses, banks, hospitals and pharmacies. Informed leaders also know that in 1900 there were 10 black medical schools; today there are three.

Too many black colleges are saddled with an obsolete business model, a lack of vision, leadership challenges in the presidency and on governing boards and a paucity of meaningful engagement among key stakeholders -- faculty, staff, students and alumni. Money from the federal government may help but it will not solve their problems.

For many survival seems the objective. That is not enough as Benjamin Mays, whose legacy is Morehouse College reminds us: “Not failure but low aim is sin.” Sustainability rather than survival must be the ultimate goal.

Now is the time for candor and self-assessment that could lead to pruning, culling and even an exit strategy. This conversation should begin with the governing board. Whether they care to admit it or not, for several reasons, some beyond their control, many HBCUs are in a death spiral and cannot be salvaged. Money alone will not suffice. Instead, support should be given to those schools willing and capable of making tough choices to achieve sustainability.

If the Trump administration makes a substantial investment in black colleges it should be intentional about which ones to support. This could be accomplished with specific inducements toward innovation and expected outcomes. Incentivizing schools to develop bold and creative solutions to the daunting challenges they face may prove to be the most consequential action possible under the circumstances.

The future of black colleges is highly dependent on effective board governance. The single most important decision a board makes is hiring a president. Although there are a few notable exceptions, in the past three decades the HBCU presidency has been characterized by instability.

This situation has been exacerbated by the recycling of leaders with a lackluster track record. For most black colleges, given their tenuous financial condition, the margin for error is just about zero. Boards have a fiduciary responsibility to get governance right.

A few years ago the governing board of Sweet Briar College conducted an extensive review and decided to close. This came as a shock to many including students and faculty. In response, alumni rallied support, funds were raised to keep the doors open, and the board was reconstituted. Recently a visionary president was recruited and a new path is being charted. It remains to be seen if these actions will sustain Sweet Briar in the long run but the board must be commended for taking action.

An effective governing board does not shrink from confronting harsh realities and making difficult decisions. The board of General Motors reluctantly eliminated Pontiac and Oldsmobile but it helped save the company. Whether the boardroom is corporate or campus, governance matters as never before. Now is the time for governing boards at black colleges to take stock and act decisively.

.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured