Opinion: Look beyond rhetoric about immigrants to see the real people, including children

Sireesh Ramesh is a north Fulton high school student who has written for Teen Ink magazine and won medals in the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards.

In this piece, Sireesh looks at the life of a fellow teen who entered the United States illegally and is trying to send money home to his family and earn a high school diploma. Sireesh met Roberto through a friend who volunteers with immigrants.

By Sireesh Ramesh

With President Trump making illegal immigration a central focus of his presidency, the 11 million illegal immigrants reportedly living in the United States are now under a national spotlight, much of it negative.

I met one of these immigrants, a 17-year-old who crossed the border to provide a better life for his friends and family back home in Mexico. (I changed his name to protect his privacy.)

Roberto comes from a small village in northern Mexico where his parents worked as laborers in the maquiladoras, foreign-owned factories dotting the border. His family’s struggle to survive increased with the birth of a baby sister. His parents were too poor to take care of two children. Sympathetic to Roberto and his family, some villagers contributed to hire a "coyote," someone who helps immigrants cross the border illegally, to transport Roberto to America. They believed, Roberto said, that it would easy for him to get a job and pay them back.

So, Roberto tucked a photo of his parents in his pocket, met the gray-haired coyote and made the 18-hour drive to Atlanta. The old man knew someone in Atlanta who would give Roberto housing for two weeks while the teen attempted to find work.

The day before the two weeks were up, Roberto found a job as a restaurant dishwasher. He also found a local charity, which eventually secured him a room to rent and helped him enroll in a local high school where he has met teachers sympathetic to his plight.

Roberto hopes a high school diploma will eventually enable him to quit his 10-hour shifts as a busboy and dishwasher and graduate to a more stable job. He talks about his dream of one day saving enough money to go to college. He does yet realize that Georgia has a law requiring undocumented students to pay out-of-state tuition, making his dream of higher education all the more elusive.

Roberto agreed to let me shadow him for a day, beginning with his morning walk to school. As Roberto walks to school, he slides his fingers across walls sprayed with gang signs and bouncy, colorful letters signifying a drug corner. He keeps his eyes to the ground to avoid the groups of gang members he passes in his 20-minute route to school. Walls of the school, built in 1972, are saturated in graffiti.

He walks hurriedly to his first-period class. He tells me in his broken English that his parents taught him to never be late. Although he moved to Atlanta only eight months ago, his grasp of the language is growing quickly. But many times he is still unable to understand the fast-paced classroom discussion.

A teacher calls on him in class. Unable to convey in English that he does not know the answer, he pouts and twists his wrists, hoping the gesture can cross the language barrier. It diverts the teacher’s attention, but stirs laughter from his peers. Roberto laughs with them, saying later the class was laughing with him, not at him. Many of his classmates are also immigrants.

Roberto gazes into the distance as the teacher’s lecture becomes too much for his tentative English. He thinks of his family in Mexico, the smell of sandalwood on his mother’s clothes, and his home. The ringing of the school bell awakens him from the daydream. He slides his backpack on one shoulder and runs out the door. He has only a few minutes before his 3:30 p.m.–1:30 a.m. shift starts at the restaurant. He rushes down the cracked streets to his apartment where he quickly changes into his uniform before sprinting to his job.

In a corner of the restaurant kitchen, unwashed plates tower all around him. Most are filled with more than half-eaten food, an insult to Roberto who struggles to afford three meals a day. Humidity rises from the steaming water until Roberto’s once clean white uniform is soaked in sweat. It does not break his concentration.

After his shift ends, Roberto goes to the only vendor open at 1:30 in the morning, an old man who sells food from a rusty trolley with a faded yellow umbrella. Roberto buys the food and cracks a quick joke. They both chuckle. Before he leaves, Roberto nods his head at the vendor, who silently nods back, both acknowledging their temporary struggles in a hope for a better tomorrow.

Roberto goes back to his apartment and finishes dinner. He manages to squeeze in a little bit of homework before showering and sleeping. He goes to bed at 3:30, setting his alarm at 6:30 for the next school day.

Roberto told me there had been many times when his employer refused to pay him or threatened deportation if he did not sacrifice sleep to work four or five hours overtime. A simple work permit or temporary visa could stem the problems Roberto faces, but many politicians don't want to offer either to illegal immigrants. There are charities, including several in Atlanta, that assist the thousands pouring across the border with no skills or money, but without a permit or visa, Roberto will continue to work overtime and have little chance of going to college.

Adrian Godoy, a volunteer at the English teaching section of one local charity, said, “Most of the immigrants we help came here illegally. But I’ve been noticing more and more illegal immigrants coming to our charity without any money or even a family to support them.”

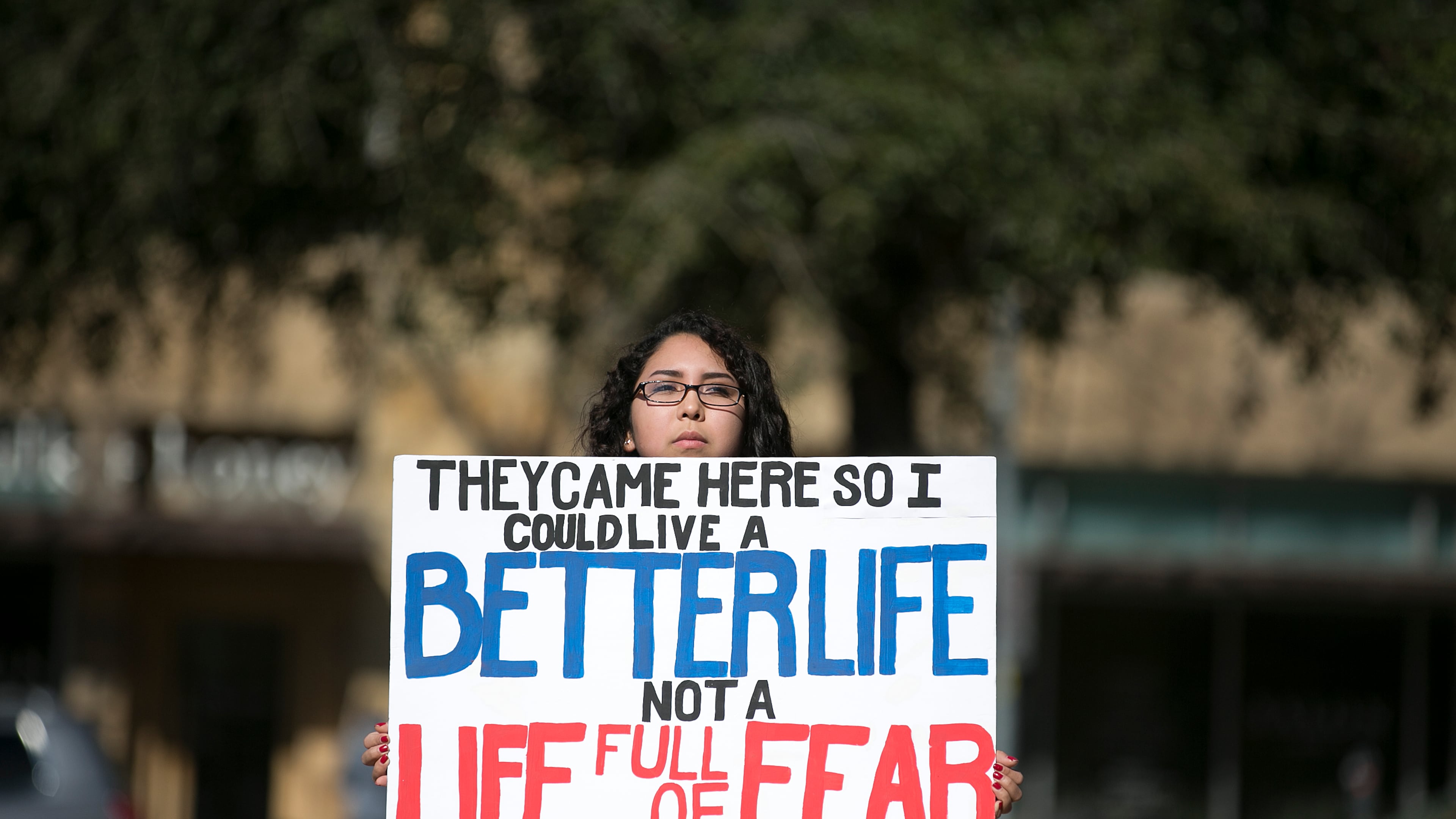

The struggles of those like Roberto should lead Americans to confront an important moral question: Are we okay with perpetuating the suffering of 11 million people simply because they came into the country illegally?

More Stories

The Latest