Nestled deep in the woods north of St. Louis sits a mystical place called Ours that many people have searched for but few have encountered. The secluded town of Ours was established in 1834 by a conjure woman named Saint after she swept across the South wielding a serpent staff while freeing the enslaved. And so begins poet Phillip B. Williams’ epic work of speculative historical fiction, “Ours,” a transcendent and lyrical exploration of freedom that delivers a fluid, spiritual and empowering meditation on the complexities of reclaiming identity.

At the heart of this story is Saint, a woman who emerges on a plantation in Arkansas seeming to “appear out of their combined suffering.” Saint unleashes the White Plague, destroying plantations “without any bloodshed but plenty of death” as the slaveholders rapidly die off. She then leads the newly freed to a secluded township called Graysville, secures possession from the founder using a combination of cash and conjure, and renames her utopia Ours.

Saint’s first objective is to heal her flock from the internal bondages of enslavement. She leads a mesmerizing revival at a nearby creek. A frenzy of contorted bodies and fluttering eyelids induce “a new way of being, a new way of thinking” that free the inhabitants of Ours — known as the “Ouhmey.”

Gris-gris and magic form the foundation of Ours and Saint deploys them to protect both her town and people from outsiders seeking to disrupt their progress. “‘Ours’ is my attempt at creating a contemporary mythology for Blackness in the United States of America,” Williams states in the author’s note. He goes on to detail his knowledge of African spirituality, hoodoo and conjure used to craft the magical town and vibrant inhabitants.

Saint’s spells deliver varied results and seem targeted to benefit the worthy. It’s not only slaveowners affected by the White Plague, but anyone who “had ever thought at any point in time that Negroes were less than human.” While crowds of people stand nearby untouched, seemingly random individuals are devoured by pestilence.

Folks seeking freedom from enslavement can locate the town’s entrance; those looking to reclaim the freed slaves cannot. Curious explorers wander the wilderness searching fruitlessly for Ours. Meanwhile, the Ouhmey employed in the neighboring town of Delacroix maintain an easy path of egress. As time advances and America descends into Civil War, Ours flourishes under Saint’s tutelage. However, she discovers there’s nothing simple about freedom for those who have never known it.

Williams complicates his statement on meritocracy with his rendering of Saint’s interior. She has no memory before a storm washed her up on a Florida beach and is on her own quest to reclaim her missing past. The link between her magic and her emotions plays out through the weather, with floods and lightning presenting as her anger while also shrouding the mystery of her past. Sometimes her conjures contradict each other and cause harm, leading to complications with the Ouhmey.

One of Saint’s loudest critics is Aba, a founding member of Ours. As the years pass and their lives intermingle, Aba begins to question Saint’s methods and challenges both her authority and intentions. A violation of one of Saint’s conjures results in the birth of a child named Justice. He also has it out for the powerful woman, and their strife complicates life for numerous members of the community.

There are gorgeous threads of tenderness woven into these characters as well. “If there’s anything more shockingly unpredictable than freedom, it’s love,” Saint discovers as the residents of Ours start to heal. Miss Love chooses her name because she’s a woman who misses being loved, and Miss Wife is a man who desperately misses his wife. Their union creates Luther-Philip, a child who plays a vital role in Justice’s quest to define his identity.

Williams inflates over a dozen characters in his opus via a fluid storyline of interconnected personalities who weave in and out of each other’s lives — at different times and for different reasons. The bulk of the action that propels the narrative occurs in the beginning of the story. The story then expands on the details from differing perspectives.

As the years pass, the population of Ours grows. Saint adopts Selah and Naima, twin girls who possess their own magic. Their coming of age is fascinating to observe as they seek to harness their powers while defining separate identities. Joy and Francis arrive from New Orleans after using conjure to murder an onslaught of abusive men. Through Joy’s character, as with Naima, Williams explores how unresolved anger shapes identity. It isn’t until Joy partners with Aba that her journey of self-discovery advances.

Through Francis, an individual free from gender and time itself, Williams’ story transcends the physical. Saint and Francis seem to have known each other for much longer than either realize. It’s their quest to understand their connection that brings this 200-year story full circle in a mystical crescendo that dips into the future as much as the past.

Williams validates the novel’s nearly 600 pages by allowing his characters “space to have full selves in a freedom they deserve.” A few storylines repeat as the narrative progresses, mostly pertaining to the backstories of the central characters. But overwhelmingly, Williams has assembled a vivid and theatrical ensemble in “Ours” and given them plenty of room to access their humanity as their lives intersect and intertwine. The result is a spiritual, redemptive and stirring look at the numerous shapes autonomy takes.

FICTION

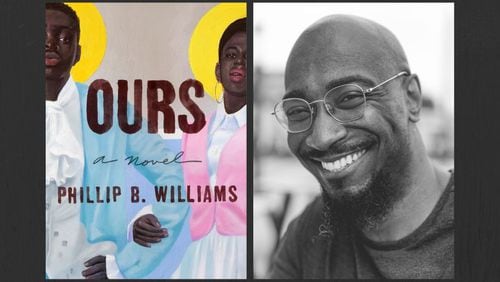

“Ours”

by Phillip B. Williams

Viking

592 pages, $32