Martin Luther King Sr., as he usually did, rose early for church on the morning of June 30, 1974.

His wife, Alberta King, was still asleep.

Credit: Copyright Estate of Christine Ki

Credit: Copyright Estate of Christine Ki

On Saturday night, her daughter Christine and two of her grandchildren stopped by to bring some dinner, but she had been restless all night and had trouble sleeping.

King Sr., known affectionately as “Daddy King,” was scheduled to fly to New Jersey that afternoon, and she always worried when he traveled. She begged him not to forget his topcoat.

But she was also excited. The longtime musical director of Ebenezer Baptist Church, which her family built from the ground up, would be playing with the M.L. King Senior Choir.

At about 6:30 a.m. Daddy King called his 20-year-old grandson Derek King. He asked him to be at the house by 9 a.m. to drive Big Mama, as she was known by her grandchildren, to church.

Daddy King left the house before his wife got up.

He forgot his topcoat.

When Alberta King woke up, she put on a black dress with yellow flowers and had breakfast beneath a wooden sign in her kitchen that read: “Kill them with kindness. It’ll drive them crazy.”

At around 7:30 a.m., Willie Carl Elder, a local taxi driver, drove Marcus Wayne Chenault from the downtown bus station to Ebenezer.

It was his 23rd birthday.

Elder said there was something weird about Chenault, but he couldn’t put his finger on it. Chenault smiled during the entire ride and paid Elder $5 on a $1.60 fare.

He asked Elder if the whole King family attended Sunday morning services. Elder told Chenault that he didn’t know.

I sure would like to meet them, Chenault said, smiling.

Verse I: The unthinkable

Within hours, Chenault would “meet” the King family.

Exactly 50 years ago today, in a two-gun barrage, Chenault would murder the family’s matriarch, Alberta Williams King, as she sat at her church organ, and 69-year-old deacon Edward Boykin. He would shoot another woman in the chest and scatter bullets across the church, leaving holes still visible today.

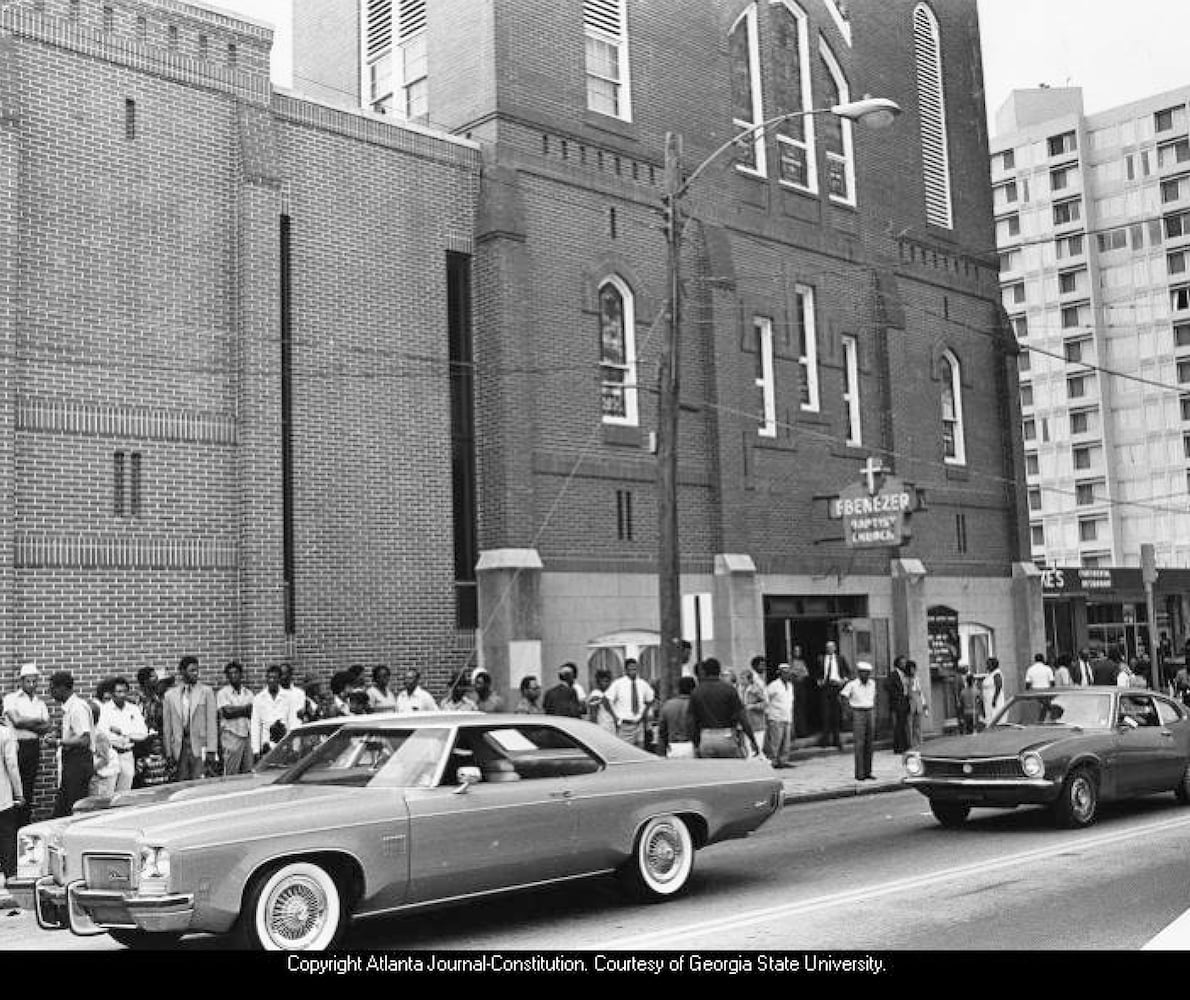

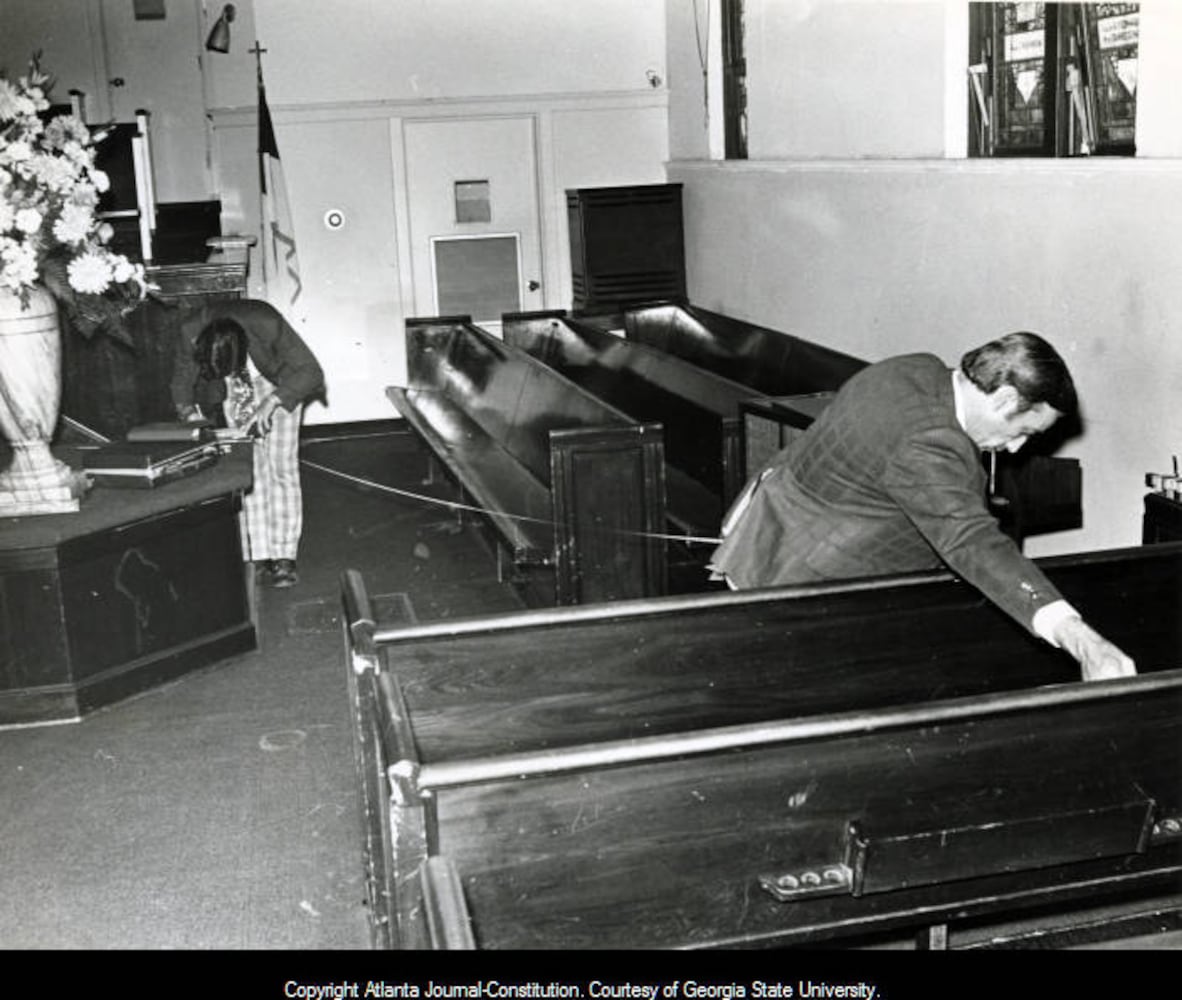

As horrific as the story is, it is one that is largely untold. Last week on a recent tour of the church, which is now part of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, a park ranger retold the story, just a few footsteps from where it happened.

Not one of the 20 or so people had ever heard about the shooting.

“My uncle’s shadow is so huge that it blocks a lot of us out,” said Isaac Farris, a grandson of Alberta King, who watched the tour from the balcony.

Family members hope to change that this weekend with commemorations honoring Alberta King. On Sunday, the 50th anniversary of her death, Ebenezer will honor her with a special program, “Faith Over Fear, Love Over Hate,” featuring family members, as well as Sen. Raphael G. Warnock, the senior pastor of Ebenezer, and Rep. Lucy McBath.

The musical selections she was scheduled to play that Sunday will be played in her memory.

Six years before her death, in 1968, her middle son, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was gunned down in Memphis. A year later, her youngest son, Alfred Daniel “A.D.” King, mysteriously died at the bottom of his swimming pool.

But not even the King family could fathom sitting in the protective arms of Ebenezer and watching Big Mama die.

Before noon that day, tragedy visited them again.

Credit: Jessica McGowan

Credit: Jessica McGowan

Verse II: Big Mama

Alberta Williams King was born in 1904, the only surviving child of Jennie Celeste Williams and Adam Daniel Williams, who served as pastor of Ebenezer from 1893 until he died in 1931.

As the daughter of one of Atlanta’s most powerful preachers, Alberta enjoyed the privilege that came with her father’s tenure. She attended high school at the prestigious Spelman Baptist Seminary before enrolling in Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute, where she obtained her teaching certificate.

She didn’t teach long.

On Thanksgiving Day in 1926 at Ebenezer, she married the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. They moved into the upstairs bedroom of her parents’ Auburn Avenue home, where King Jr., and his two siblings, Willie Christine and Alfred Daniel, were born.

“Just as sure as the grass is green around the stump,” Daddy King would often sing to his wife, whom he called Bunch, “you are my sugar lump.”

“My grandmother was like a big best friend,” said Angela Farris Watkins, the youngest of 11 grandchildren. “She instilled the importance of being loving and being kind.”

Credit: Angela Farris Watkins

Credit: Angela Farris Watkins

Alveda King, her oldest grandchild, described Big Mama as a beautiful woman who was always “incredibly well-dressed, with a wonderful sense of humor. And she always smelled good with the softest skin.”

The glue to the family, she possessed a quiet strength that was flexible enough to nurture King Jr. well into adulthood, while threatening enough to bring “heat to the seat” to Angela and Bernice King for sliding down the stairs in her Boulevard home.

“She meant business,” said Bernice, whose middle name, “Albertine,” came from her grandmother.

Big Mama expected all of her grandchildren, even the grown ones, to come to church on Sundays.

“I was a divorced woman of 23. I was dating some guy, and I was less often home than I would be at his house,” said Alveda King, her oldest granddaughter. “At that time, I might come to church. I might not.”

In the days leading up to June 30, Big Mama called her first grandchild.

Please come to church, Big Mama told Alveda.

“I told her I would see her Sunday,” Alveda said.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

Verse III: Who was Marcus Wayne Chenault?

Isaac Farris, the oldest son of Christine King Farris, is still befuddled by Marcus Wayne Chenault some 50 years later.

“It is almost like he just appeared,” Farris said. “He was just weird, man.”

Chenault arrived in Atlanta from Dayton, Ohio, on a Greyhound bus. He had dropped out of Ohio State University the semester before.

His sister, Nancy Chenault White, told the Atlanta Constitution at the time that Chenault was a “normal guy. But then, you know that when you go off to college you get your own ideas. Really, though, his mind must have snapped.”

Chenault stood just 5-foot-2 and wore thick “Coke bottle” glasses. In nearly every photograph published before and after the shooting, he is laughing or smiling. Friends said he posed no physical threat although he could be “verbally violent.”

He was raised a Christian, but friends told the newspaper that a newfound hate for Christianity intensified in the months leading up to the shooting.

When a friend told him he was moving to Atlanta, Chenault said he looked forward to visiting. When the friend told him to look him up, Chenault said, Don’t worry, you will find me. I’ll be in the papers.

Verse IV: ‘A pair of eyes … watching me steadily’

On that Sunday morning, after Chenault was dropped off at Ebenezer, he realized he was too early. He walked to the Holiday Inn at 175 Piedmont Ave. and checked into a room at 8:04 a.m.

At 9:30 a.m. another cabdriver, Jimmy Smith King, delivered Chenault back to Ebenezer. He was carrying a brown, soft plastic case. Inside were two pistols: a .32 caliber wooden-handled Smith & Wesson and a .32-20 caliber pearl-handled Spanish revolver.

Dressed in a tan knit suit with no tie, Chenault was greeted by Melvin R. Waples, who invited the stranger to his men’s adult Bible class.

Because of King Jr.’s legacy, Ebenezer had become somewhat of a tourist attraction. On some Sundays there seemed to be more visitors than parishioners.

Credit: Charles Pugh

Credit: Charles Pugh

Walking through the church, Daddy King noticed the faces of people he didn’t know.

“As I moved toward the staircase to start back up to my study, there was a pair of eyes … turning away, being swallowed up in the crowd, but somehow, through all of that, watching me steadily,” he wrote in his memoir.

Longtime church members, including Big Mama, worried about the regular influx of visitors.

“She always said, ‘King, one day somebody gonna come in that church and shoot somebody,’” Alveda recalls. “She was prophetic. There was no great explanation, but we all knew we were in a fishbowl. What did they say in Job? ‘For the thing which I greatly feared is come upon me.’”

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Verse V: Readying for the service

Derek King arrived at Ebenezer with Big Mama around 10 a.m., more than enough time for the 10:45 a.m. service.

Big Mama went to the choir room to get ready.

Angela, who was 10 years old at the time, came looking for her.

“She turned and saw me, and she shook her head like, ‘No, you can’t come in here. Go where you’re supposed to be’,” Angela remembers.

Angela went to the nursery to watch and play with the babies during the service.

“That was my last look at her before she passed,” Angela said. “I am glad that God led me to her. I was able to lock eyes with her before she passed, probably 30 minutes later.”

Isaac walked past the choir room and the two exchanged waves. He had no intention of chatting.

After Sunday school, he and his cousins Dexter and Vernon would run to Carter’s, the neighborhood store across the street, to buy bubble gum and candy.

They would always get back once service started and sit in the balcony.

“There was nothing different about the morning,” Isaac said. “Nothing seemed out of place.”

Verse VI: The Amen Corner

Days before the shooting, Derek told his grandfather that he was thinking about going into the ministry. On the spot, Daddy King told him to sit in the pulpit on Sunday.

He took a seat in one of five chairs on the pulpit — the last one on the left of where the preacher would stand. It was closest to Big Mama’s organ and the Amen Corner, a three-pew section of the church on one side of the sanctuary where the elders usually sit.

The first seat of the last row was within arm’s length of Big Mama’s organ.

After Sunday school, Chenault took a seat in the Amen Corner. No one told him the area was reserved. He sat in the third row next to Big Mama.

Mrs. Jimmie Mitchell, 65, sat down beside Chenault and introduced herself.

“I’m Mr. Chenault,” he replied. They shook hands. He asked if Rev. King was there, and Mitchell pointed him out. He was seated near the piano on the other side of the pulpit in a big wooden chair with green leather cushions. Christine was seated in the first pew facing the pulpit.

The Rev. Calvin Morris, who was to preach that morning, gave the call to worship.

Everyone closed their eyes and bowed their heads. As she had done at Ebenezer for decades, Big Mama began playing “The Lord’s Prayer.”

It was about 11:05 a.m.

Verse VII: Chaos

When the first shot rang out, it reverberated through the church and stunned the congregation into silence.

“I look over at my grandma and she is holding her face and smoke is around her head,” Derek said. “This dude was standing up over her with two revolvers. I couldn’t comprehend what I was seeing.”

Credit: Bill Mahan

Credit: Bill Mahan

Chenault broke the silence when he shouted, “I’m taking over here this morning.”

Daddy King recognized the wild-eyed Chenault as the same man who had stared at him earlier.

Big Mama slumped and fell off her organ bench. Chenault shot her again, this time in the back, just inches from her spine.

“I’m taking over this (expletive),” Chenault shouted as he produced a second pistol. “I’m going to kill everyone in here.”

Chenault shot Mitchell, whose hand he had just shaken, as she tried to dive to the floor. He jumped through the Amen Corner and leapt into the choir stand. Bullets flew everywhere.

He ran into Boykin, who had been a member of Ebenezer since moving to Atlanta in the late 1920s to work as a chauffeur. Chenault shot him point blank in the chest, killing him.

“All of a sudden, I heard a lot of screaming and Calvin Morris telling everybody to remain calm,” said Angela, who was in the nursery listening to the service over the intercom.

Chenault fired seven or eight shots in the church, according to testimony and police reports. When he ran out of bullets, he tried to reload his guns.

During that momentary lull, Derek, who had taken cover under the Communion table, saw his opening.

Still built like the cocky high school football star he was just two years earlier, Derek ran toward Chenault, who tried to escape through a back door.

With Derek chasing him, Chenault pulled the trigger twice and misfired both times.

Derek caught up with Chenault in the back hallway. In 1969, when he was just 15 years old, Derek had found his father A.D. King at the bottom of his family’s swimming pool, dead. His death was ruled an accident, but family members still contend A.D. King was murdered.

Derek said the hidden rage surrounding his father’s death exploded, so he paid no attention when Chenault begged, Don’t hit me! Don’t hit me!

“I almost killed him,” said Derek, who was a sophomore at Morehouse. “They pulled me off him because if they had left me with him, he would be dead because I wasn’t going to stop.”

While Issac, Dexter and Vernon were still picking out their candy, a church usher ran into Carter’s store and asked if anyone had a gun. They are shooting up the church!

The three cousins ran back across the street, fighting through the mob running away from it.

“I knew my family was in there,” Isaac said. “We didn’t have a true sense of how much danger we potentially would have been put in ourselves.”

When they got to the church, the stairway leading to the sanctuary was littered with abandoned wallets, shoes, hats and pocketbooks.

Isaac, Dexter and Vernon made their way into the sanctuary where they found Big Mama laid out in front of the pulpit, her head in someone’s lap.

Blood was everywhere.

Ushers held Daddy King back as he fought to get to his wife, screaming, I can’t leave here without Bunch.

Isaac fell to his knees next to Big Mama.

“I can almost see this as if it was yesterday. She looked up at me calmly and asked me how I was doing,” Isaac said. Her calmness gave him a false sense of security that she was going to be all right.

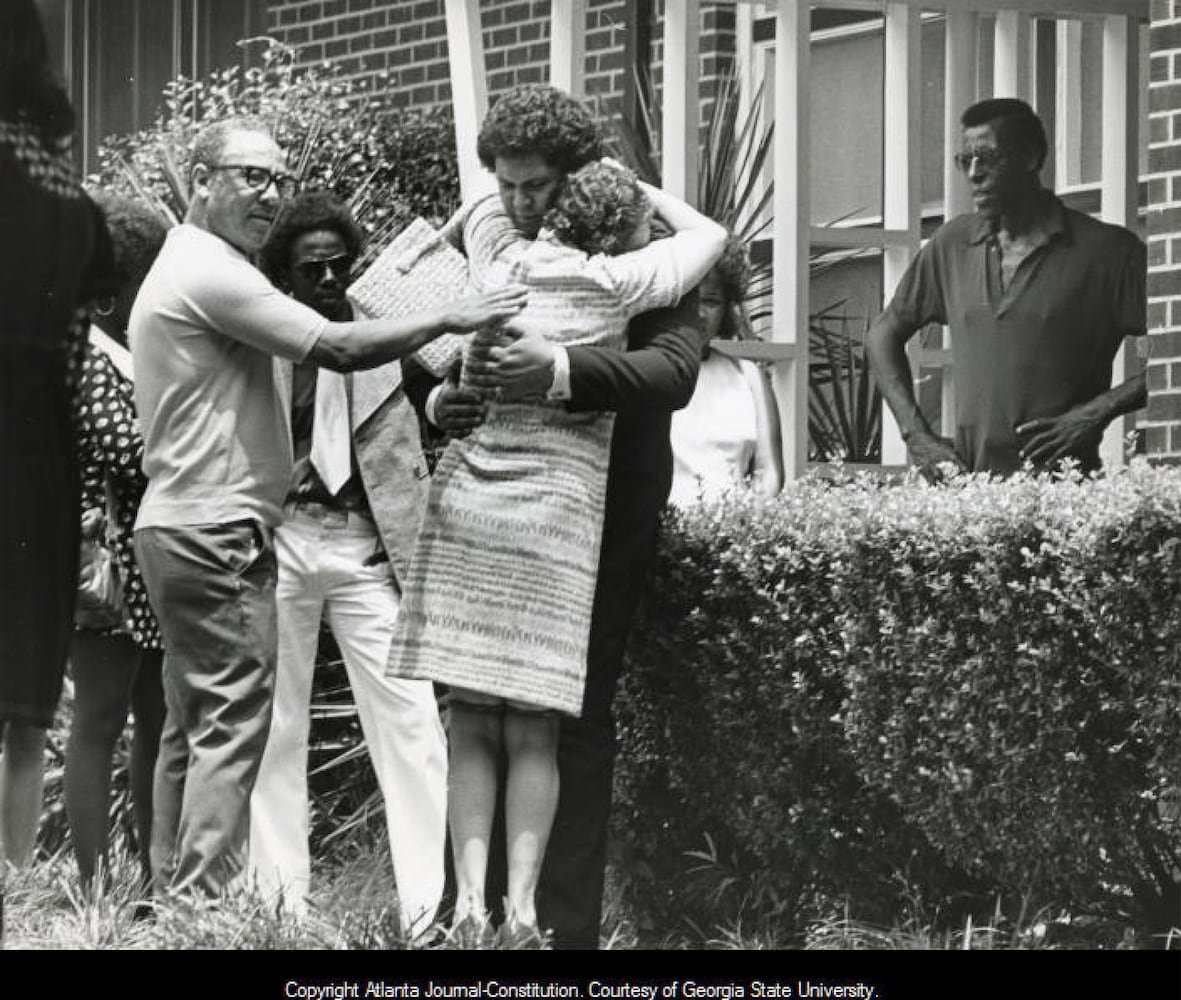

Driving a burnt orange Nova, Yolanda King pulled up at the church with her brother Martin Luther King III and Bernice.

Coretta Scott King was in Chicago and was supposed to call them early that morning to make sure they got up for church. But because of the time difference, she called late, making her kids late. They arrived in the middle of a madhouse.

A deacon ran up and told them their grandmother had been shot.

“It was providential that we were late,” said Bernice, who was 11 at the time. “It was best that I wasn’t there. I can’t imagine the person I’d be today.”

At the same time, Alveda and her boyfriend pulled up at the church. She saw the ambulance and then saw her mother, Naomi King, jump in the back of it. She ordered her boyfriend to follow the ambulance.

“I didn’t think about who it might have been in the ambulance. It could have been granddaddy. It could have been Aunt Coretta. It could have been anybody,” Alveda King said. “Daddy had been killed. Uncle M.L. had been killed, so trauma was not new to us.”

“I am glad I didn’t ignore her when she said come to church,” Alveda said. “How would I have felt if I didn’t go to church, and she got shot? I just kept saying I am glad I came.”

When they got to the hospital at 11:15 a.m., Angela remembers holding her mother Christine’s hand in the dimly lit waiting room as the family had started to gather.

“I could just feel the deep sadness, shock and fear in her,” Angela said.

Someone came into the waiting room to get Christine. Your mom is asking for you, the person said to Christine.

Christine told her daughter to stay in the waiting room.

“But I’m still frightened and all these people are in here and that is my best friend,” Angela said. “You are going to see her, but I’m not?”

She was pleading with her mother not to leave her when a second person walked into the waiting room and announced that Big Mama was dead.

“I felt very badly that maybe I wasted a few moments that she could have spent with her mom,” Angela said. “That’s just something that, as a 10-year-old, I carried.”

Dr. Asa Yancey, medical director of Grady Hospital, said Big Mama died from a gunshot wound to the back.

All measures were used to maintain her life, he said. But Mrs. King was pronounced dead at 11:50 a.m.

The waiting room, now filled with church members, as well as the family, was silent.

Verse VIII: Confronting the shooter

Credit: BILLY DOWNS / AJC file

Credit: BILLY DOWNS / AJC file

Daddy King learned that Chenault, who was frothing at the mouth when police peeled his limp body off the Ebenezer floor after Derek’s beating, was being treated at Grady.

Daddy King, along with Isaac and Dexter, set out to find him.

“We walked around, the three of us,” Isaac said. “I could see Marcus Wayne Chenault lying there.”

Daddy King was allowed to walk right up to Chenault.

Why did you shoot my wife? he asked.

I came to shoot you, but I didn’t see you, Chenault said matter-of-factly. So, I shot your wife.

Son, I will pray for you, Daddy King said.

Isaac, who talked openly with his cousins about ways to kill Chenault, was stunned by the exchange.

“That was our grandmother,” Isaac said. “She was the lover. She was the embracer. She was the support. So for somebody to take her out like that while she’s in the church, doing her church duty, it shook us. That challenged our whole commitment to nonviolence.”

Credit: Dwight Ross Jr.

Credit: Dwight Ross Jr.

Verse IX: ‘Thank God for what you have left’

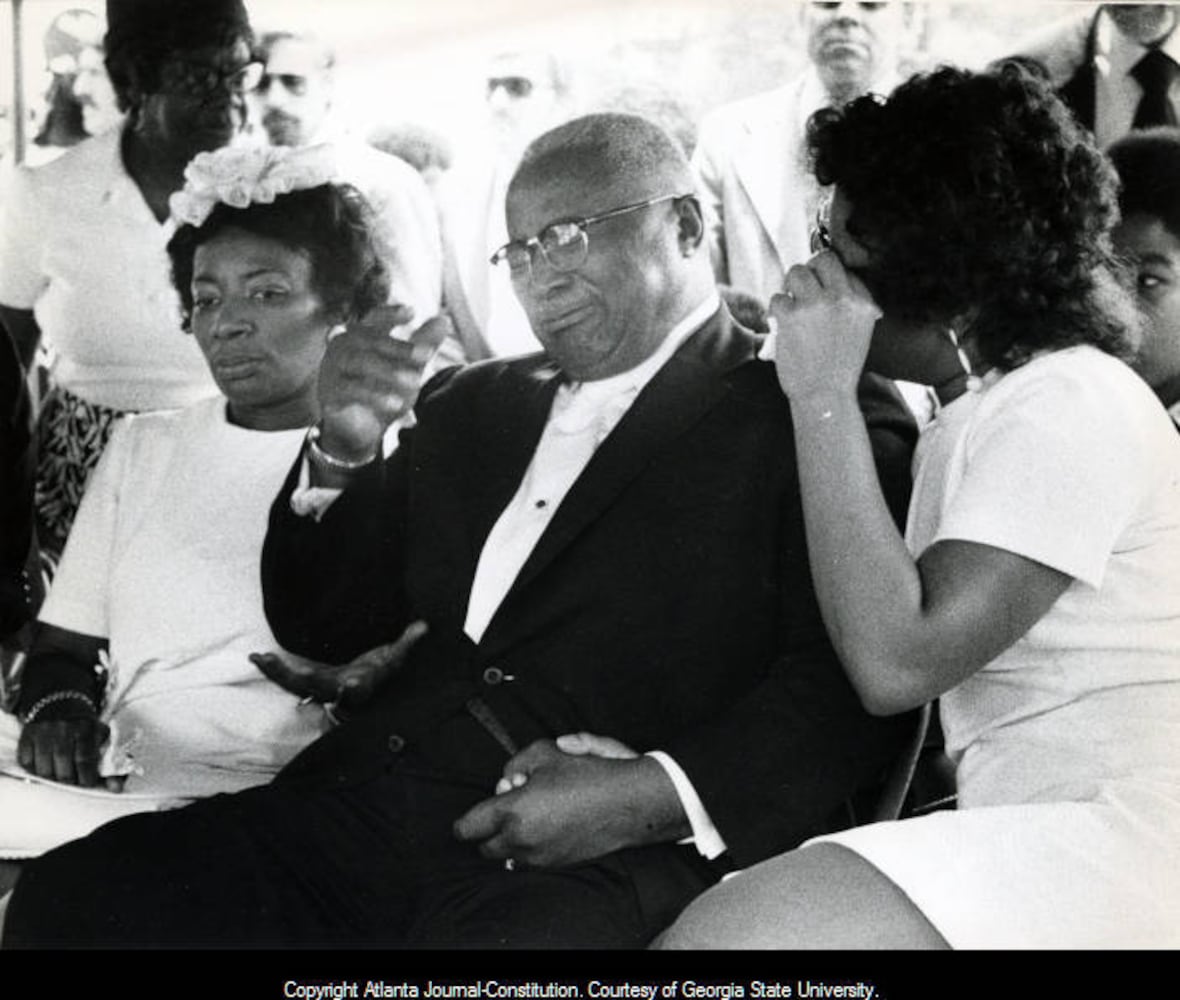

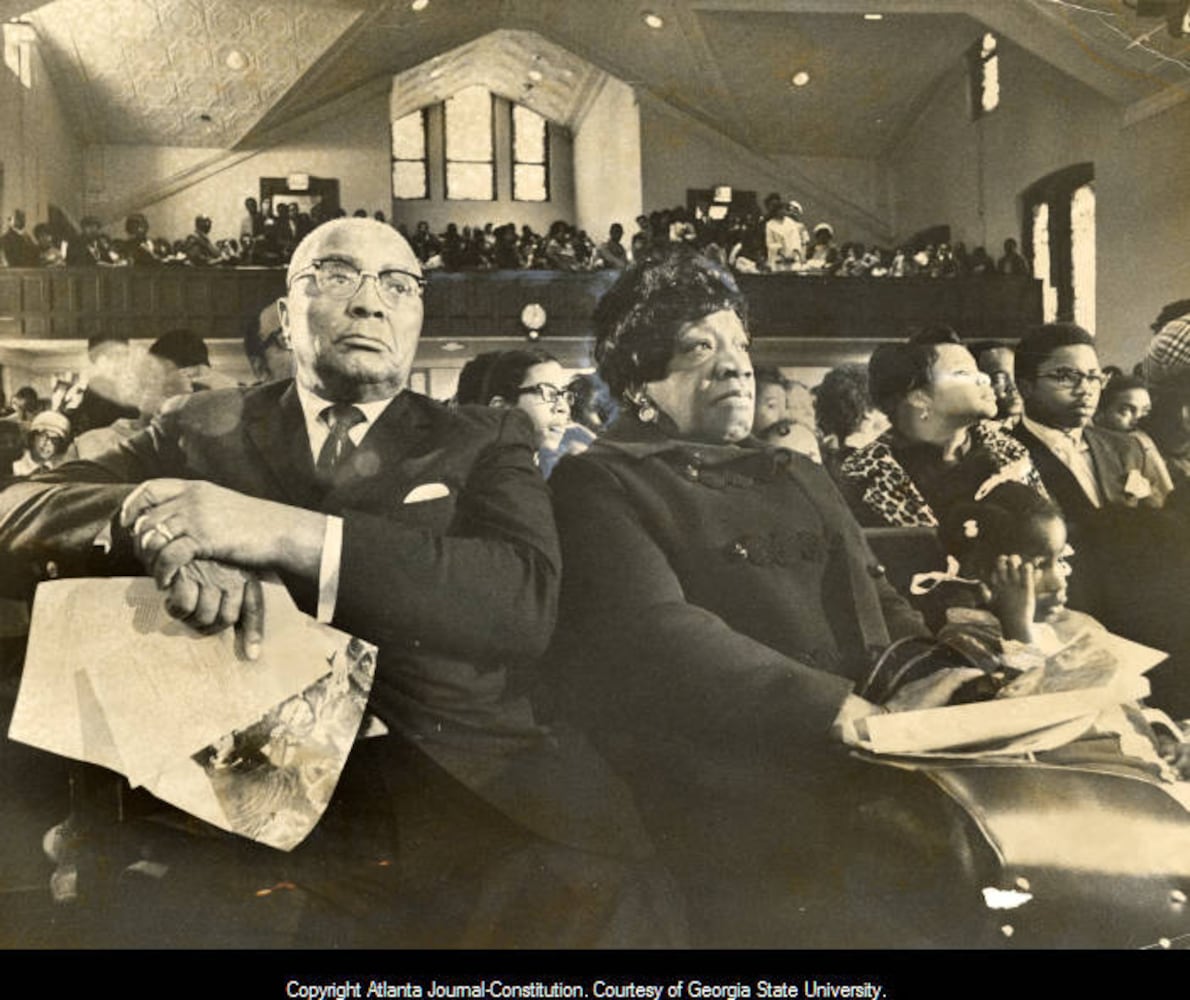

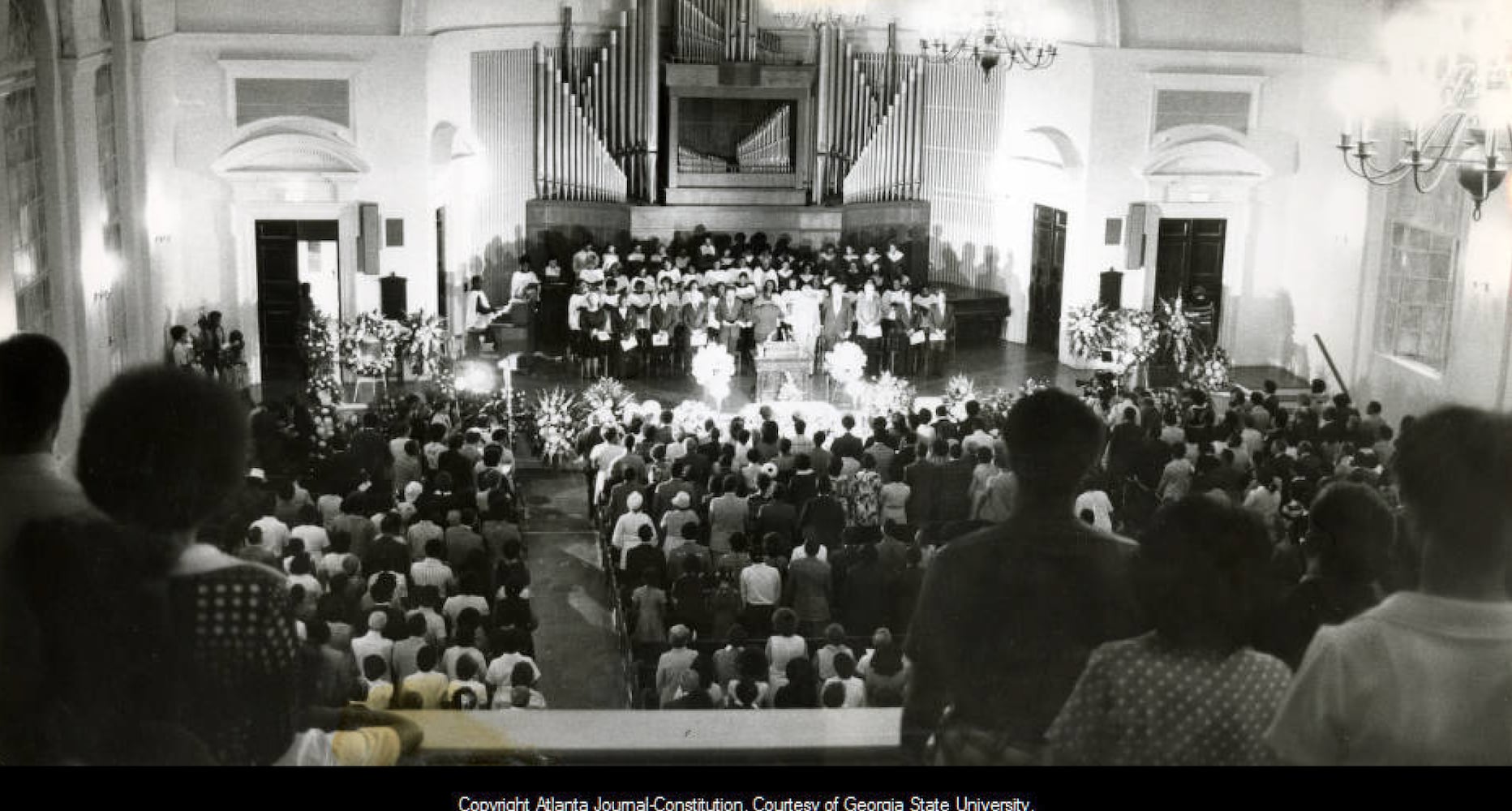

On July 2, Big Mama’s memorial service was held at Sisters Chapel on the campus of Spelman College.

Andy Young officiated the funeral the following day at Ebenezer, saying, “We come to give thanks for a wonderful life and a loving heart.”

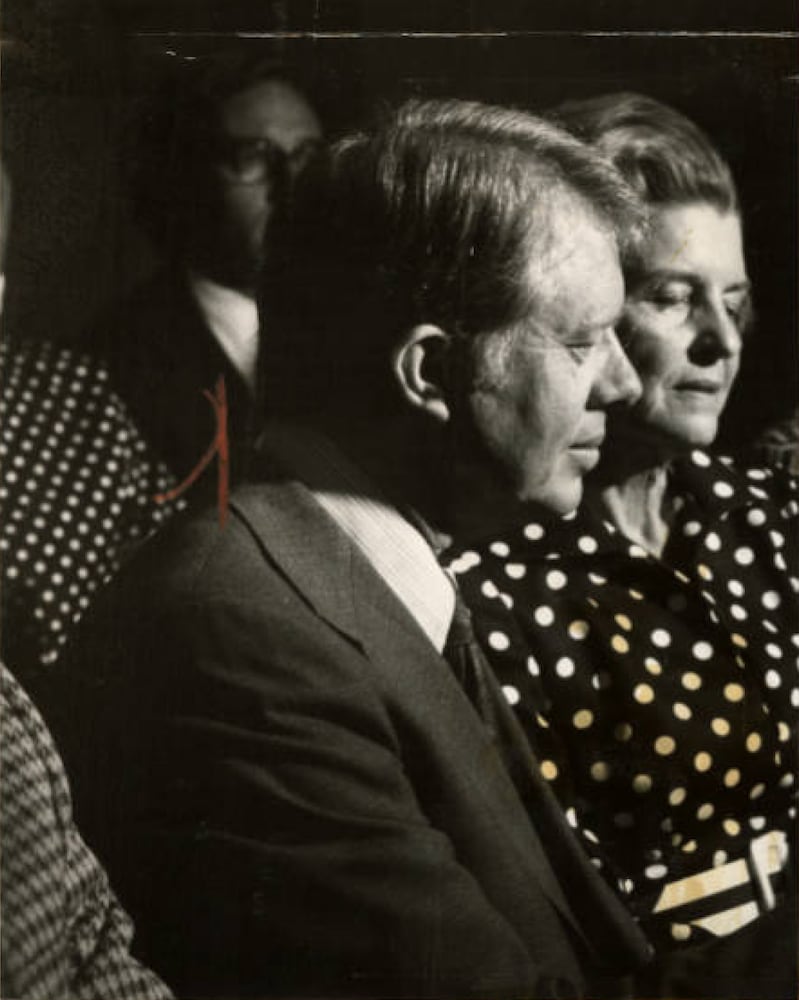

More than 600 people, including Gov. Jimmy Carter; Betty Ford, the wife of Vice President Gerald Ford; and newly elected Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson crowded into Ebenezer. Comedian Flip Wilson sat next to Moms Mabley.

Another 3,000 people were outside — it had already reached 90 degrees by 10 a.m. — listening to the service from loudspeakers.

Big Mama’s closed pale pink casket was shrouded with flowers and rested just feet from the organ. At times, Daddy King wept uncontrollably.

“I’m not going to quit. I’m going to let nothing stop me,” Daddy King said. “Thank God for what you have left.”

Alberta Williams King was buried at South-View Cemetery, and placed in the same double crypt that six years earlier had contained the remains of King Jr.

Verse X: The trial

Immediately after Chenault was charged with murder and aggravated assault, the FBI explored the possibility of a conspiracy.

Chenault had what police described as two “death lists” with the names of people he wanted to murder, including King Sr., Reverend Ike, Aretha Franklin, Ralph David Abernathy, Hosea Williams and Jesse Jackson, who lived in Chicago.

Detectives in Ohio found among his possessions an unused bus ticket for June 15 to Chicago. He had written on it, “Father’s Day Massacre canceled.”

Authorities determined that Chenault acted alone and on Sept. 12, 1974, he was sentenced to die in the electric chair under a new capital punishment law passed by the Georgia legislature in 1973.

Credit: Minla Linn

Credit: Minla Linn

When his sentence was read, Chenault shook violently in his chair and stuck out his tongue as if he were in an electric chair.

But for more than 20 years, Chenault’s attorneys launched appeals to get the death sentence, pushed by former Fulton County District Attorney Lewis Slaton, overturned.

Finally, on June 21, 1995, after more than two decades on death row, and in part because of the efforts by the King family, Chenault was re-sentenced to life without parole.

In forgiving Chenault, Daddy King made it clear he did not want to see him executed. The King family, who preached nonviolence, were adamantly against the death penalty.

“Capital punishment is against the better judgment of modern criminology and, above all, against the highest expression of love in the nature of God,” King Jr. said in 1957.

In a 1981 speech, titled, “The Death Penalty is a Step Back,” Coretta Scott King said despite the assassinations of her husband and mother-in-law, she still “unequivocally opposed the death penalty.”

“An evil deed is not redeemed by an evil deed of retaliation,” she said.

Big Mama’s grandchildren, even those who wanted to kill Chenault, agree with the decision.

“I’m proud of that because that’s what was instilled in us,” Isaac said. “We’re very credible when we talk against the death penalty. Because we lived it.”

Verse XI: Deep scars from lives lost

In the weeks after the shooting, metal detectors were placed in Ebenezer’s entrance. Bernice remembers one Sunday when a bulb from a television news camera exploded during service and everyone ducked.

Daddy King didn’t return to the pulpit until September. A year later, he retired from Ebenezer.

“He realized for the first time, that he was doing this job alone,” Isaac said.

Credit: COPY

Credit: COPY

In 1976, two years after the shooting, tragedy hit the family for the fourth time since 1968 when Darlene King, a daughter of A.D. King, died of a heart attack while jogging on the track at Southwest High School. The Spelman sophomore was only 20.

For all of the King grandchildren, the shooting of Big Mama — on the heels of Martin and A.D.’s deaths, followed by Darlene’s death — left deep scars. They wondered who would die next and why God was punishing them.

“With all 11 of the grandchildren, I could talk for hours about how that pain, tragedy, shock and trauma showed itself in each one of us,” said Angela, who has taught psychology at Spelman for 29 years. “We carried, and carry, a lot of unresolved pain.”

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Credit: Jenni Girtman

After Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, Bernice pleaded with her mother, Coretta Scott King, not to travel because she feared that she too would get shot. The girl would look at family photos to try to figure out who was going to die next.

Bernice’s fear and paranoia grew into such raging anger after Big Mama’s murder that her mother feared for her well-being. She could snap at a moment’s notice.

“I lived very dark thoughts, and I was very afraid that death was around us constantly,” said Bernice, who entered the ministry at age 17. “My grandmother was shot at church, which is supposed to be a safe place. It was just very confusing and perplexing to me, and I held on to all of that for so long.”

Angela still has vivid dreams of her grandmother and remembers going to therapy a few times after the shooting. Derek relied on his faith to carry him through. Isaac leaned on his parents. Alveda said she never had fear.

Five of Big Mama’s 11 grandchildren died relatively young. At least three of them died from heart attacks. Bernice said her brother, Dexter, who died earlier this year of cancer, never recovered from having witnessed Big Mama’s murder.

“We are the manifestation of the casualties of a civil rights war,” Angela said. “With every war, there are casualties and sometimes those casualties are physical. Many times, they are emotional. Many times, they are both.”

Verse XII: Death of the gunman

On Aug. 3, 1995, less than two months after his death sentence was overturned, Chenault suffered a massive stroke at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center, where he was being held.

He was in a coma for weeks before dying quietly on Aug. 19. He was 44.

“In the spirit of nonviolence, we are pleased that he was spared a violent death,” Christine King Farris said at the time. “Unlike the violence which he inflicted upon my mother which led to her death as well as the death of others.”

Coda: Still Standing

Ebenezer Baptist Church was founded in 1886, nine years after Reconstruction ended. Its longtime home on Edgewood Avenue beginning in 1918 closed as an active church in 1999, when its congregation now numbering 6,000 moved across the street into a gleaming new building.

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Angela is still a member of Ebenezer, the only church she has ever known. She was married in Ebenezer and her daughter, Farris, was baptized there.

Her mother and grandfather’s funerals were held in Ebenezer. So were many of her cousins, including Darlene King in 1976 and Dexter Scott King earlier this year. Politicians, from Barack Obama to President Joe Biden, include it on their swings through Atlanta.

Visitors continue to be drawn to the church and on occasion, they will come up to Angela after service and ask for a photo.

“Somebody innocently told them that I am Dr. King’s niece, right? I am OK with it. But sometimes,” she said, “it’s a little scary.”

The Players

Alberta Williams King (Big Mama): Mother of Martin Luther King Jr. and musical director of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Martin Luther King Sr. (Daddy King): Father of Martin Luther King Jr. and the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

THE GRANDCHILDREN

Alveda King: Oldest grandchild.

Derek King: Son of A.D. King, who captured the shooter.

Angela Farris Watkins: Daughter of Christine King Farris and the youngest grandchild.

Isaac Farris: Son of Christine King Farris.

Bernice Albertine King: Youngest daughter of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King III: Namesake of Martin Luther King Jr., could not be reached for this story.

Big Mama and Daddy King’s five remaining grandchildren have all died.

ABOUT THE STORY

Senior Social Media Producer Ron Williams, AJC researcher Sandi West, Presentation Specialist Pete Corson and photographer Natrice Miller contributed to this story. Reporters culled through more than 20 years worth of articles from the Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution, as well as sworn testimony, court documents, police reports and firsthand accounts from five of Alberta King’s six remaining grandchildren. Other resources included the books “Daddy King,” by the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr.; “Growing Up King,” by Dexter Scott King; “Through it All,” by Christine King Farris; “King,” by Jonathan Eig; and “The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation,” by Anna Malaika Tubbs.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured