The Black experience comes into focus in one man’s art collection

Over his collecting lifetime, Atlanta physician Dr. Otis Thrash Hammonds amassed hundreds of artworks from the mid-19th century to contemporary pieces that now live in the 450-works strong Hammonds House Museum collection.

When Karen Comer Lowe joined Hammonds House as executive director and chief curator in the summer of 2021 she wanted to highlight the museum’s vast collection of works by nationally and internationally known Black artists as well as the deep representation of Atlanta artists.

Her initial dip into the Hammonds House collection, on view through the end of January, is called “Exhibiting Culture: Highlights of the Hammonds House Museum Collection” and includes 50 works hung throughout the historic West End home.

Perhaps even more than usual, there is an intimacy and warmth in seeing artwork featuring some of art history’s bright lights hung in the high-ceilinged rooms of this vintage Victorian. That feeling of personal connection is only underscored in the charming 1977 collage of nine black and white images taken by Atlanta photographer and arts patron Lucinda Bunnen of Hammonds hosting guests in his art-filled home, where in a meta-moment, works on view today are visible behind him.

There are pieces in “Exhibiting Culture” by heavy hitters like Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Elizabeth Catlett, James Van Der Zee and Mildred Thompson. And throughout the exhibition there is a mini-history of the Atlanta art scene in works by Kojo Griffin, Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier, Amalia Amaki, Radcliffe Bailey, Yanique Norman and Larry Walker. The locals, as always, hold their own.

For a time it was almost impossible to visit a group show in the city without seeing work by Linnemeier and Amaki. Though Radcliffe Bailey’s career trajectory has eclipsed those two artists, all three share an interest in making mixed-media shrine-like works ornamented with found objects and infused with reverence. That connective tissue can be seen in Linnemeier’s “A Place Called Freedom,” where Isaiah T. Montgomery — founder of the all-black community of Mound Bayou, Mississippi — wears a halo of cowrie shells, or in Amaki’s moving work “Family Jewels,” in which black-and-white photos of Black ancestors are lovingly framed with humble pearl buttons and the brass butterfly clutches that secure military medals. In Amaki’s hands those humble objects become as precious as the gold leaf on a religious icon.

Some of the most memorable works in “Exhibiting Culture” are the most evanescent, like the delicate ink on paper drawing “Pool Shooter” (1972) by Georgia-born Benny Andrews. Andrews displays his wonderful economy of gesture to emphasize the insouciant style of one lanky pool player — all Giacometti angularity — who wears a jaunty bandana tucked into his back pocket as he bends over to make his move. A true American original, don’t miss the interview with Andrews — who later in his career would go on to instruct the next generation of talent like David Hammons and Kerry James Marshall — playing on the museum’s back-room video screen. Charles White delivers an equally unexpected, alchemic gem in “Vision,” of an upturned woman’s face emerging like a phantom from the surface of a sterling silver plate — a vision herself, or a witness to one.

Like so many of the artists on view here, offering correctives to ugly cartoons and hateful stereotypes, the dignity of White’s African American subjects was foremost. He saw his art as enmeshed with politics and Black liberation, a fact attested to in many of the artist quotes presented as yard signs on the Hammonds House front lawn.

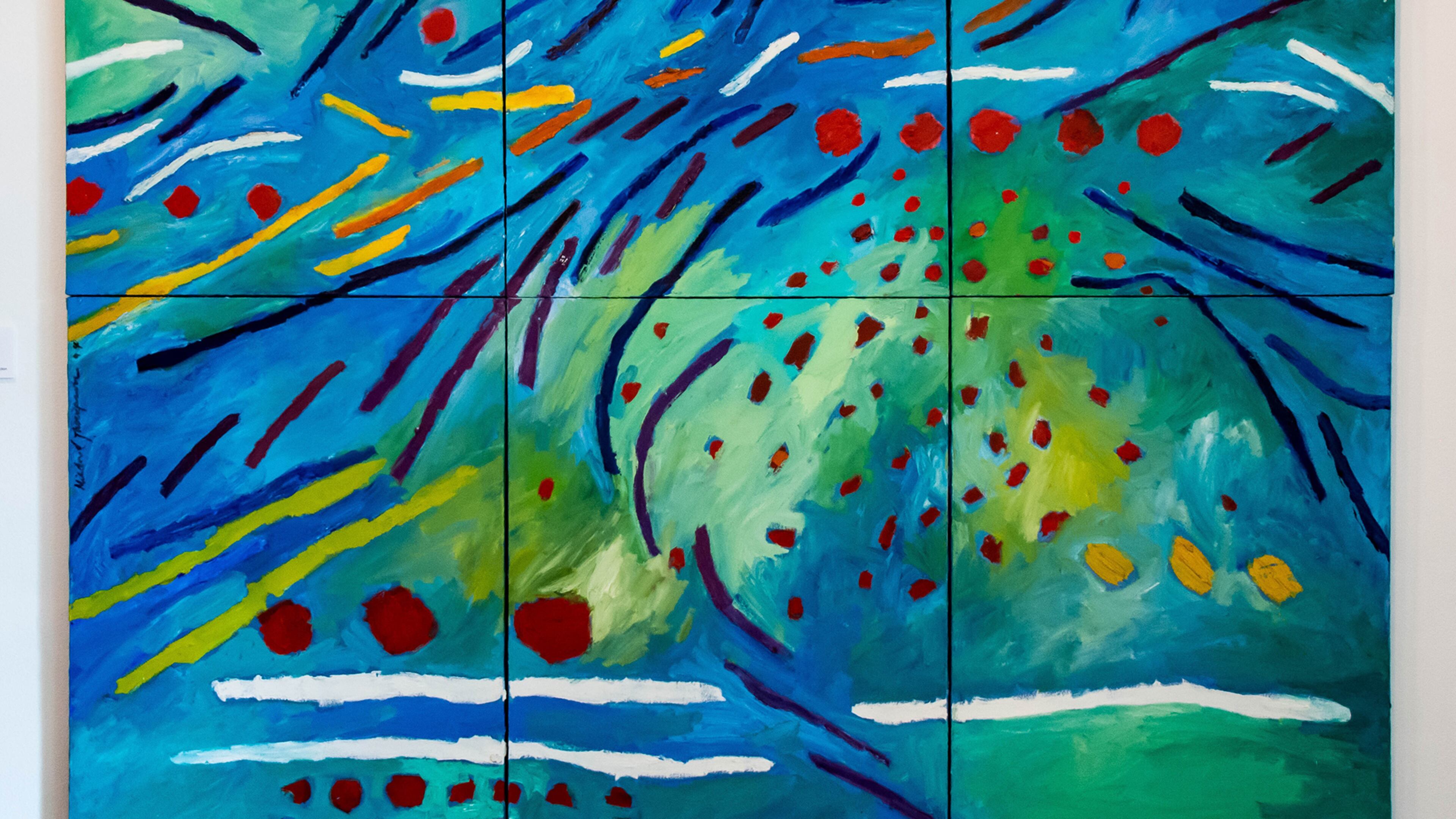

There is a balance in “Exhibiting Culture” between bright, ebullient abstract works by Mildred Thompson and the verdant, Gaugin-inspired watercolor nudes from Romare Bearden on view on the museum’s second floor which can feel like an afterlife corrective to more somber works on display below. That sense of sobriety found on the first floor is typified by Andrews’ nightmarish image of a man consumed by an inferno in “Plight” or in Bill Traylor’s haunting hieroglyphics that make “Exhibiting Culture” a complex window into the Black experience via art.

VISUAL ARTS REVIEW

“Exhibiting Culture: Highlights From the Hammonds House Museum Collection”

Hammonds House Museum is closed through spring 2022. 503 Peeples St. SW, Atlanta. hammondshouse.org.

Bottom line: Work that is both joyful and despondent offers a window into how the artworks collected by Atlanta physician Otis Hammonds express the Black experience.