Robert Frost’s yearly visits to Agnes Scott College

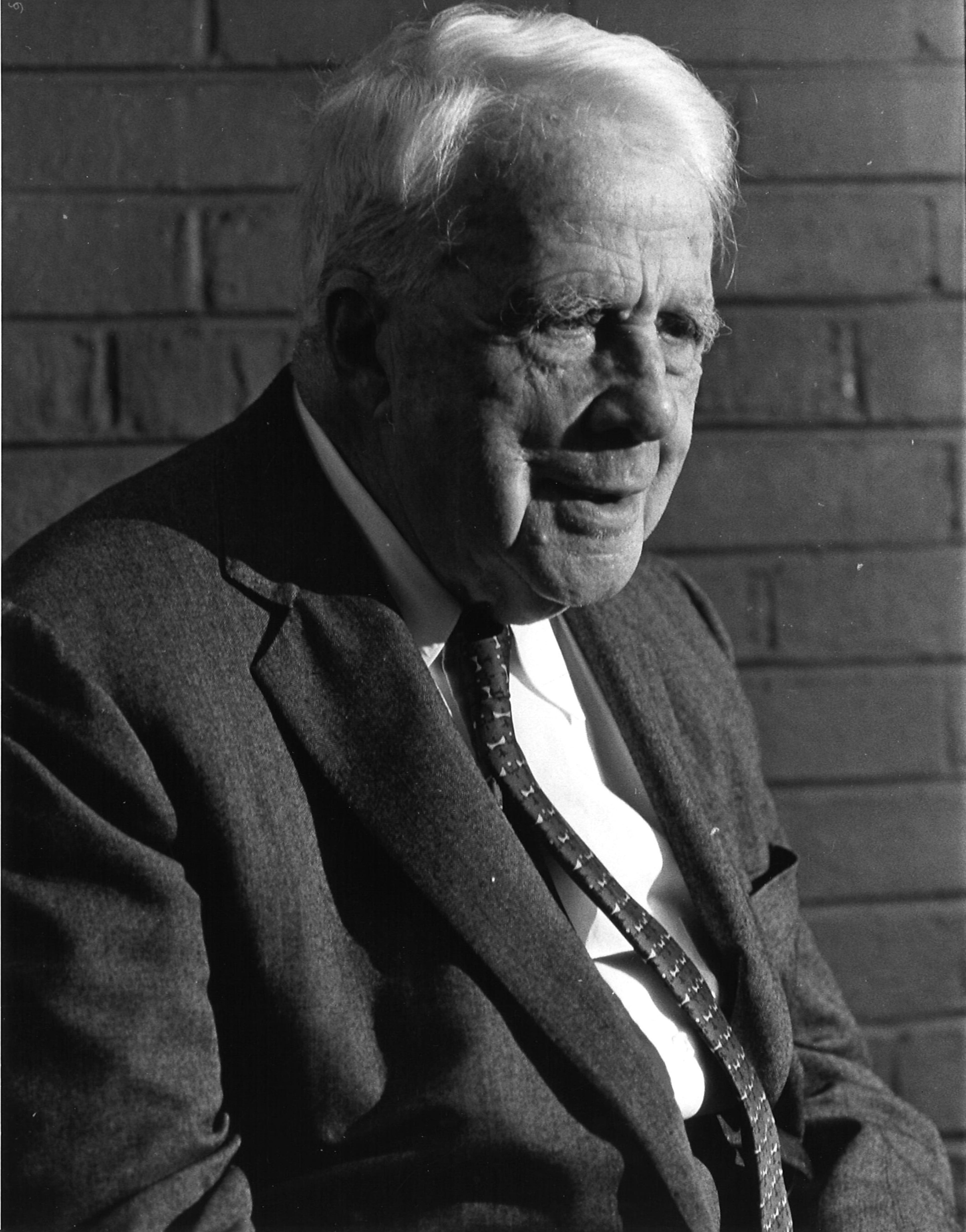

Each January he’d arrive by train, an elderly, white-haired man in a rumpled suit and a winter coat too warm for Georgia, on his way from New England to a snowbird’s winter break in Florida. He’d stay a few days, take solitary nighttime strolls, and talk to students and faculty, sometimes rambling a bit, about what he had written, but never about what it meant.

For years, Robert Frost, the best-known American poet of his time, loved stopping by Agnes Scott College, the private women’s liberal arts college in Decatur, and the campus loved him stopping by. He visited 20 times, giving poetry readings and informal talks to packed audiences. This year marks the 60th anniversary of his last visit, in January 1962, and since April is National Poetry Month, it seems an opportune time to remember this largely forgotten chapter in Atlanta history.

“He is still a name to conjure with,” said Casey Westerman, College Archivist and Librarian at the college’s McCain Library, which maintains a large collection of his books and papers. “But he is not mentioned much among students.

“Recently another librarian was walking a student assistant through the library,” he continued, “and they were on the second floor near the oil portrait of Robert Frost. The librarian mentioned, ‘You see the portrait of Robert Frost here?’

“And the student said ‘Robert Frost? I thought that was Bernie Sanders.’”

In addition to the portrait, Frost can still be found today at Agnes Scott as a sculpture in the Alumnae Garden, and in the Robert Frost Collection, about 72 shelf feet of private papers and first editions that Frost himself donated, along with handwritten poems and audio and video recordings of some of his visits.

Frost is one of the last of the giant literary figures who once were celebrated in the way that TV celebrities are today. Well known for “The Road Not Taken,” “Birches” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” he received four Pulitzer Prizes for poetry and the Congressional Gold Medal. President John F. Kennedy invited him to read his poem “Dedication” at his inauguration, but when the glare from the sun was too bright for him to see the paper in front of him, Frost, then 86, famously recited “The Gift Outright” from memory instead.

Frost’s relationship with Agnes Scott began in 1935 when he was invited to lecture at the college by English professor Emma May Laney. He returned in 1940 and then, starting in 1945, came every year until his death in January 1963 at age 88, which occurred during the week reserved for his annual visit.

Frost typically stayed at college president Wallace M. Alston’s residence.

“If you took this man for a kindly, lovable old New England poet whose charm lay in his simplicity, you were in for a shock,” Alston wrote in a commemorative brochure the college printed in 1976.

“His conversation was often quixotic, paradoxical, and enigmatic. He was independent in his judgements, quick in repartee, and impatient with questions that he regarded as silly or impertinent.

“There was one question that Robert Frost consistently refused to answer — a question that I have heard people put to him scores of times in the years that I have known him: ‘What did you mean in this poem?’

“His usual answer was to freeze up, as believe me, he could do, and to say, ‘You don’t want me to tell you in other and worse language, do you?’”

Linda Hubert, an English professor who was also in the Agnes Scott senior class of 1962, recalled hearing Frost read poems on his last visit.

“He was, in these moments, our poet,” she recalled in a 2001 program for the dedication of the statue of Frost by sculptor George W. Lundeen.

“[After his death] I remember feeling bad for the senior class following mine, and for the college,” she continued. “That relationship with Frost was a defining characteristic of the college. It was in the very rhythms of the place.”

Frost usually gave a public talk and reading in Gaines Chapel and attended a private dinner for faculty at Alston’s house.

“No one missed those gatherings,” English professor Margaret W. Pepperdene recalled in that 2001 program. “These get-togethers were called ‘Conversations with Robert Frost,’ but that is a slight misnomer. Frost liked to do most of the talking.”

The Frost sculpture shows him writing the manuscript for his famous poem “Acquainted With the Night”:

“I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain — and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light."

When his duties were done, Alston recalled, the old poet would relax at the president’s house, watch a little late-night TV, drink some 7-Up, and put on his hat and coat and go for a solitary walk in Decatur in the night.

“He wanted it that way,” Alston said. “He asked only for a key and to be let alone.”