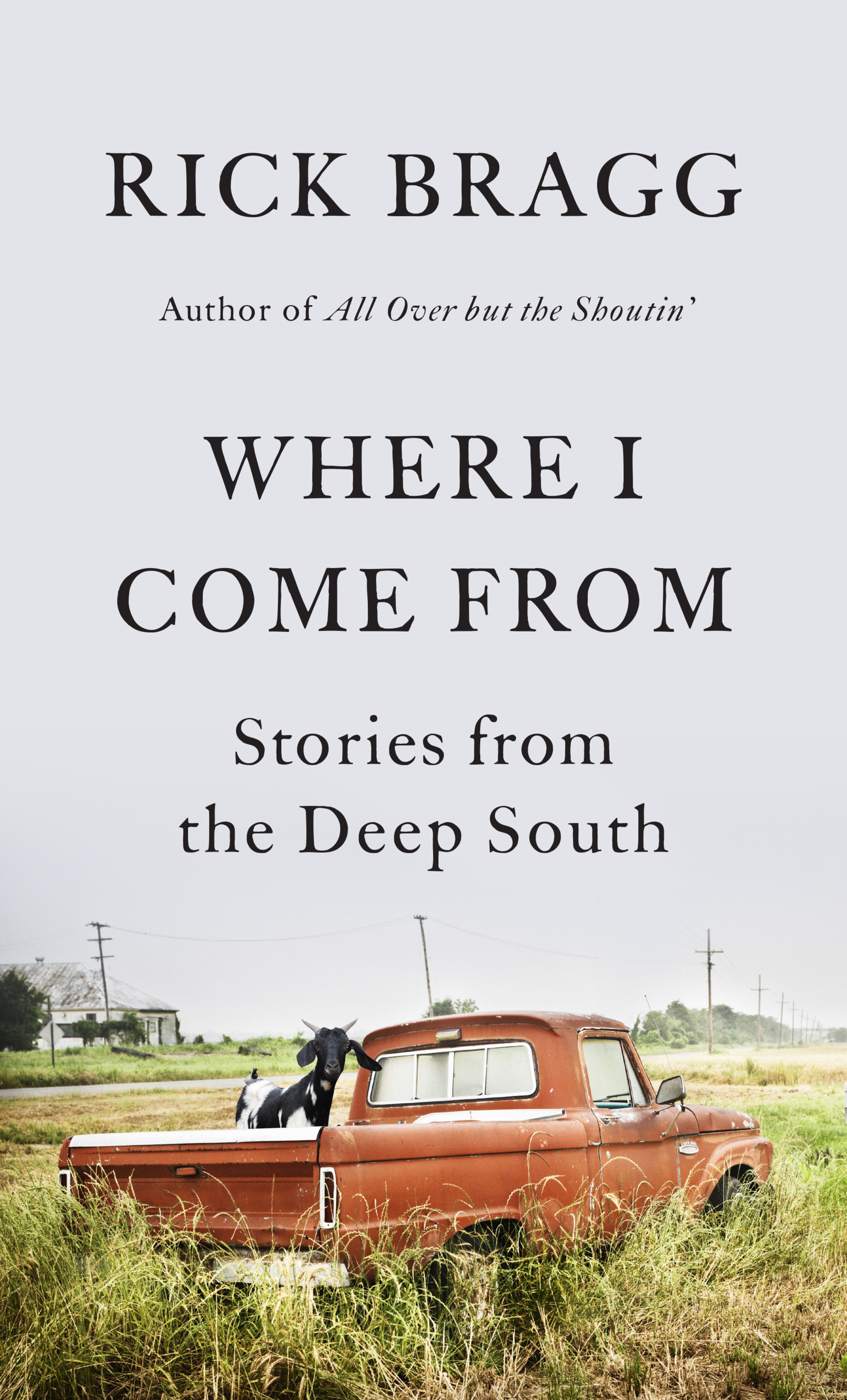

The prologue of Rick Bragg’s new essay collection, “Where I Come From: Stories from the Deep South,” lays out two important things: what readers are not going to get, and what they’re not welcome to give.

The introduction is a heartfelt tribute to his Aunt Jo, but embedded within it is a disclaimer of sorts. The author, born in Alabama in 1959, quickly establishes that the “book is not intended to be a cold-blooded examination of the South.” It feels like an acknowledgement that while many people are reading up on this region’s role in historic and current racial injustices after national uprisings this year, that’s not the subject you’ll get here.

Instead, it’s largely about the good — the people and things “that make this place more than a dotted line on a map or a long-ago failed rebellion.” Take his Aunt Jo, for instance, who he paints as a bona fide force that was “uninterested in waving anyone’s battle flag.” She brings us to what readers aren’t free to give.

Jo was his “ringer” — a guaranteed and proud fan of everything he ever wrote — and she died recently. So in an unabashed attempt to cut off negative criticism at the head, Bragg simply instructs: “if you read these stories and you have something bad to say, I would keep it to myself.”

Not that the best-selling author (“Ava’s Man,” “All Over but the Shoutin'”) and winner of Pulitzer Prize and James Beard awards needs to worry much. Over the past decade or so, nearly all of the book’s 70-plus columns were previously published in Southern Living or Garden & Gun magazines. Although it’s not a treasure trove of new material, there’s something special to be gained from these selections being bound up under one roof. Passing references in one essay show up later as full-blown stories, in both clear-cut and abstract ways.

A short paragraph about finding the digger of Paul “Bear” Bryant’s grave in one essay becomes the crux of another. References to bead necklaces hanging in trees appear three times: once as a brief, glorious comparison to creamy red beans; another time as the star of his favorite New Orleans memory; and again in a retrospective on the competitive excitement of Carnival. Threads like that make the book an intimate study on how fleeting moments make up one’s personhood. It’s a fascinating glimpse into the elaborate, emotional filing system that is a writer’s mind.

The stories are categorized by nine dinner party-safe themes, such as sports, food and beloved institutions. For readers who snag this tome in the short window between its publishing and Halloween, skip ahead to the “Haunted Mansions” section. It’s full of insights on imaginative homemade costumes, the pace of old horror movie monsters and wealthy people inheriting apparitions. “Every Southern hotel, mansion or plantation has a ghost, either a creaking Confederate colonel wailing over his doomed ideals or a gauzy young woman searching the halls for her lost cotillion.”

Then keep rolling into the “Christmas in a Can” segment for narratives about lasting holiday traditions. Some are snarky, including letters to and from Santa and a missive to Mr. President. Others resonate in their sentimentalism, like the vulnerability of expressing true gratitude at Thanksgiving, or how Christmastime brings out the kid in Bragg’s older brother. The “Relations” section, about familial bonds and home, also seems appropriate for this time of year.

But with the new year comes new beginnings, and that’s where you can start in 2021. Southerners can safely assume that the first section, “If It Was Easy, Everyone Would Live Here,” has a lot to do with the heat and insects that seem to be perpetually on attack. There’s also a whole column dedicated to the insanity trapped drivers feel while sitting in Atlanta’s gridlock.

Atlanta is referenced numerous times in the book, mostly in the form of slight digs, although Bragg assures us he loves it — he “even lived here a while, close enough to the Krispy Kreme bakery to wake up smelling sugar.” It so happens that the city is honored with being the last word of the epilogue, as it’s the connection between him and people who have never been to the South. “'Well,' they always say, ‘I did once fly through Atlanta.’”

“We Will Never See Their Like Again” holds eulogies for Billy Graham, Pat Conroy and Harper Lee — she scores two entries — but Bragg’s homages to souls unknown to the general public shine brighter. Reading about his Uncle Jimbo’s grand tales brings to mind the father in Daniel Wallace’s “Big Fish.” A story that initially appears to be about an epic, months-long rainfall transforms, in Bragg’s signature way, into a memorialization of a dog named Skinny. A column written in response to the deadly “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which didn’t fall neatly into any of the other themes, finds a home here. Bragg also pays respects to a photojournalist, a folk hero known as the Goat Man and, in a section called “The Sporting Life . . . and Death,” a high school football superfan from the nostalgic author’s hometown.

The tenderness of discussing the departed is offset by “Faux Southern,” a section containing the self-described “crotchety relic’s” commentary on the bastardization of Southern culture, such as modern country music, too-hot hot chicken and sophisticated women driving big, shiny trucks. Each essay won’t connect with everyone, but Bragg’s unfeigned writing, knowing truisms and funny advice holds strong throughout this stress-allaying book.

NON-FICTION

by Rick Bragg

Penguin Random House

256 pages, $26.95

VIRTUAL AUTHOR EVENT

Rick Bragg. Reads and discusses “Where I Come From.” 7 p.m. Nov. 12. Free, registration required. www.gwinnettpl.org/authorspeaker