Jazz guitarist Grant Green didn’t want his son to follow in his footsteps. Green was a contemporary of Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell; he was overshadowed by them in the public eye during his lifetime but four decades after his death, he has taken his place with them as the three musicians of that era who essentially defined modern jazz guitar.

Grant Green Jr. chuckles at his father’s reluctance to see him become a guitar player. “My dad never really wanted me to be a musician,” he says. “He wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer. He didn’t want me to go through the stuff that he went through. Back in those days, it was a different world. It was really tough being out on the road in those days.”

When his son persisted, Green relented. He gave his son a jazz archtop guitar and even let him be a part of his band as a rhythm guitarist. “He’d never sit down and teach me,” says Green Jr. “He gave me about one week’s music lessons. The rest, I learned from watching him and mimicking him. I’d see him play, then I would go in my room and try to mimic what I saw him doing.”

Since moving to Atlanta over 15 years ago, Green Jr. has become a fixture in both the jam band and jazz scenes through his work in the bands of the late Col. Bruce Hampton and fronting his own jazz funk group. He has returned to his classic jazz roots with a new album — “Thank You Mr. Bacharach” (ZMI Records) — that is a tribute to the music of Burt Bacharach.

“I’ve always been a huge fan of Burt Bacharach, how he wrote and came up with those melodies,” says Green Jr. “It was like ear candy for me. I’ve always wanted to do a record of his songs and when I got the chance, I jumped on it.”

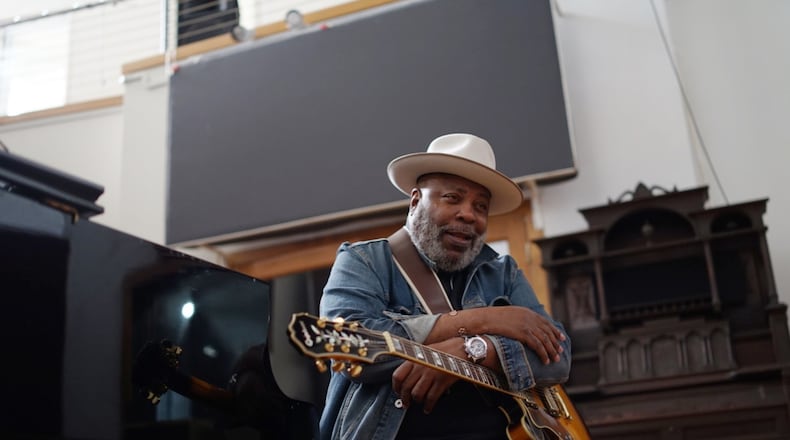

Credit: Carlos York

Credit: Carlos York

Because his father was always on the road or in New York recording at sessions for Blue Note Records, Green Jr. spent his early years in St. Louis with his grandparents. When he moved to Detroit to be with his father, it was the golden age of Motown Records. Stevie Wonder’s mother lived next door to him. The Four Tops lived around the corner. Marvin Gaye often stopped by to play quarterback when Green Jr. and his friends played pickup football games in a nearby park.

His father died in 1979 at the age of 43, and Green Jr. moved to New York City to forge his own path as a jazz guitarist. He began to go to a jazz jam at a club in Brooklyn, and it was often a humbling experience. “These guys would be looking at me, like, ‘What the hell are you playing?’ And then when the song is finished they’re telling you to get off the stage,” Green Jr. says with a laugh. “And everybody in the audience knows you’ve been dissed.”

Green Jr. had learned songs from what musicians call the jazz Fake Book. It’s a thick book with shorthand chord changes and melodies of hundreds of jazz songs; musicians can carry it with them and use it to play just about any song. Except the Fake Book isn’t always accurate, and what Green Jr. was playing often clashed with what the other musicians on stage were playing.

Hammond B-3 organist Lonnie Smith had known Green Jr. since he was a teenager and came up to him one night after he struggled onstage. “Hey, man, come over to my house,” Smith told him. “I’ll teach you the right changes.”

“I’ll never ever forget that,” Green Jr. says. “That had a huge, huge impact on me. He didn’t have to take the time to do that, but he did. He saw that I was determined. I would go up on stage and get beat up all the time, but I would come back. That’s how you learn.”

Smith had come to fame performing in George Benson’s quartet. Benson had idolized Green Jr.’s father, and became a close friend and mentor. “George would sit down and show me stuff,” he says. “And there’s nothing more intimidating than sitting down and playing with him.”

Green Jr. went over to Benson’s house once with a guitarist friend, and the three of them jammed. Benson would take something they’d played, and then add layers to it they’d never imagined. When they left, they sat in the car and laughed, looking at each other and saying, “Man, we can’t play at all, can we?”

Green Jr. would go on to record solo albums and play in a prominent trio called Godfathers of Groove with Hammond B-3 organist Reuben Wilson and Bernard “Pretty” Purdie, whom many believe is the world’s greatest drummer. His credits range all the way from Louis Armstrong to Nina Simone to Aretha Franklin to Steely Dan and many others in between.

A Godfathers of Groove show on a warm February evening at The Blue Room club in Atlanta changed the course of Grant Jr.’s life. First, he met Hampton that evening. Then during a break, Green chatted with the late Ike Stubblefield, the Atlanta B-3 player who booked the venue. Green asked if it always this warm in February in Atlanta. Stubblefield lied and told him it was.

New York City was expensive and cold. Green Jr. moved to Atlanta a few weeks later. Days after he arrived, he got a call from Hampton: I’ve got gigs this weekend, and you’re the guitar player in my band.

Hampton and Stubblefield were the only two people Green Jr. knew when he moved to Atlanta, and both were beacons of the city’s jam band scene. He became a familiar onstage figure at their shows, perched upon a stool with a left-handed D’Angelico archtop guitar and playing fast jazz-flavored runs over blues-based rock music. Green Jr. even played several “Jam Cruises” with Hampton.

“I play to a different audience now than I had been playing before,” Green Jr. says. “I’d mostly done the jazz thing with the organ trio. And I got brought into the jam band scene because of those guys.”

He began work on the Bacharach album in Atlanta in late 2019; then COVID-19 hit and the project lay dormant for nearly two years. Green Jr. originally envisioned it as an independent release. But the producers, Martin Kearns and Khari Cabral Simmons, played some of the tracks for Chad Hagan at ZMI Records (distributed by Ingrooves/UMG) and the label was eager to release the album.

“Thank You Mr. Bacharach” shows Grant Jr.’s versatility. It’s the most classic, straightforward jazz album that he’s recorded.

It also showcases his connection to his father. “My old man recorded the Bacharach song ‘I’ll Never Fall In Love Again;’ I kind of learned to phrase on the guitar from what he plays on that song,” Grant Jr. says. “My old man plays some really pretty stuff on that, and I remember sitting down with the record trying to learn it.”

The album includes Grant Jr.’s version of the same song. It echoes his father, yet explores different avenues, and for Grant Green Jr. it becomes symbolic of his own journey. He carries his father’s name and legacy with pride, but “Thank You Mr. Bacharach” demonstrates again that he has found his own unique voice on the guitar.

Credit: ArtsATL

Credit: ArtsATL

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (www.artsatl.org), is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. Founded in 2009, ArtsATL’s goal is to help build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured